Key Takeaways

- Several state agencies and private providers support youth mental health through prevention, early intervention, and treatment services.

- Tennessee makes significant financial investments in these programs but quantifying some of the state’s largest efforts is challenging.

- In general, the state’s largest and most systemic strategies and investments have been made through school health programs, community mental health centers, and TennCare.

- Recent initiatives in Tennessee, such as the K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund, focus on expanding access to mental and behavioral health services in schools.

- A separate paper in our series on child mental health in Tennessee will explore additional policy options to support children and youth.

A growing share of Tennessee youth struggle with mental health challenges, but access to mental health care can promote positive outcomes and help people function and thrive in daily life. Recognizing these trends, Tennessee has undertaken numerous initiatives to support child mental health in recent years.

In this report, we provide a snapshot of the mental and behavioral health services[1] available for Tennessee children and adolescents across the continuum of care from prevention to treatment. Our prior report in this series examined the available data on the state of youth mental health in Tennessee, and a forthcoming follow-up analysis will identify additional opportunities in this area.

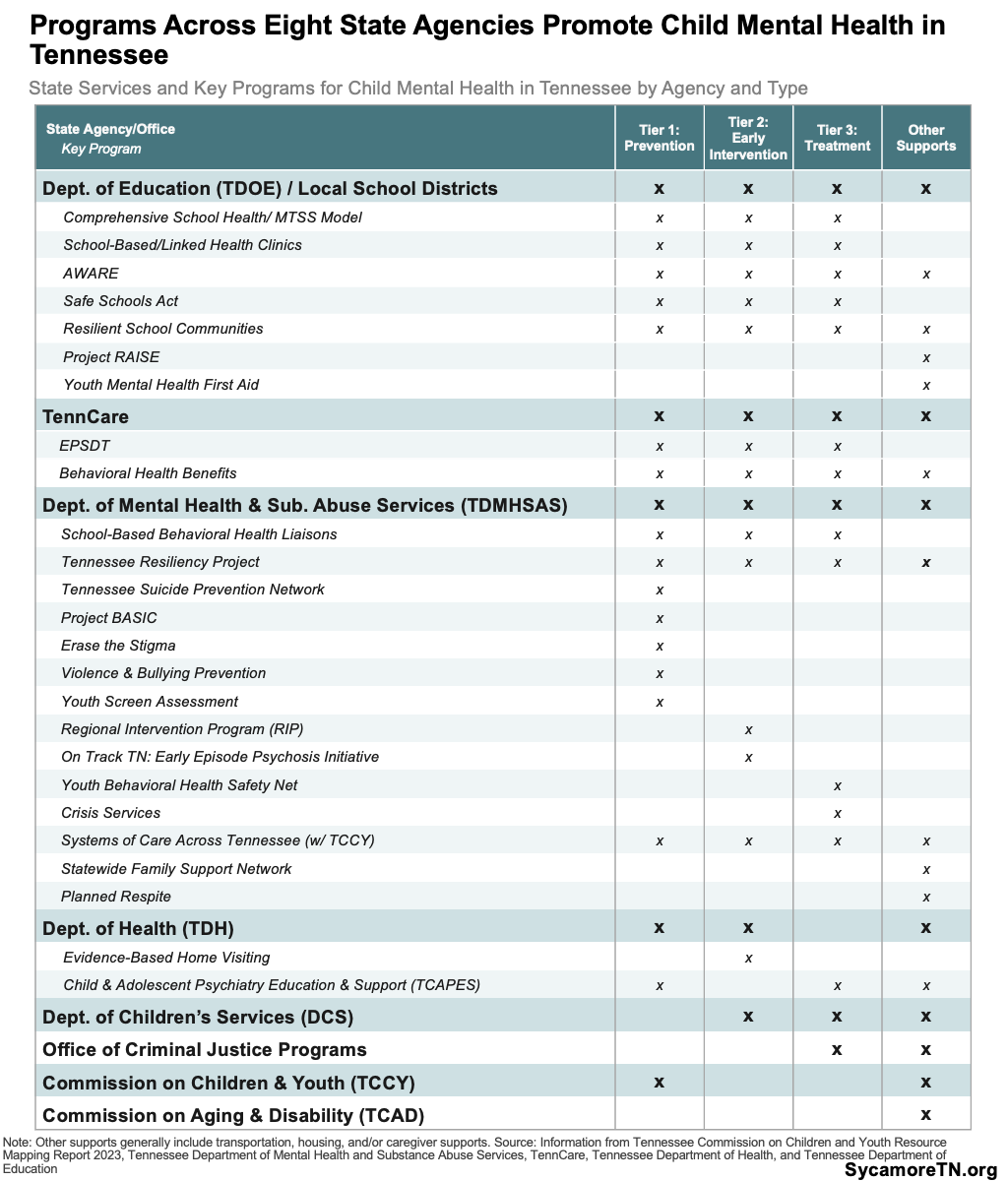

Navigating This Report

This report explores programs and services to support youth mental health through prevention, early intervention, and treatment. It begins by explaining the professionals who provide mental health services and where that occurs. We then provide additional details on key services and programs and categorize them by type of care. In addition, a section at the end highlights recent state and federal initiatives, Where available, we report funding estimates and reach for each program. Table 1 lists the state agencies that provide mental health services directly or indirectly. Appendix Table 1 includes a full description and a more comprehensive list of all programs and services offered in Tennessee.

Services aimed at promoting mental health are often categorized based on the following tiers:

- Tier I – Prevention includes activities that support positive mental health to prevent the onset of behavioral health conditions. School- and community-based prevention includes promoting a positive school climate for students, raising mental health awareness to decrease stigma, and screening for mental health conditions. (1)

- Tier II – Early Intervention targets youth identified as experiencing mild symptoms or being at risk for a mental health condition. In schools, for example, this can include short-term activities such as group therapy, mentoring, and low-intensity support in the classroom. (2)

- Tier III – Treatment supports youth with mental health conditions. Treatment can include a range of supports, depending on the type of condition and severity — including individual and group therapy, medications, residential treatment, inpatient hospitalization, and crisis stabilization. (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

- Other Supports include activities that, for example, target factors that can influence one’s mental health (e.g., housing, caregiving) or seek to improve the mental health care ecosystem (e.g., workforce support).

Child Mental Health Providers and Settings

There are many different professionals who work to support and improve mental health among infants, children, and adolescents. Mental health professionals work in a variety of settings, including schools, homes, hospitals, and specialized mental health facilities. Community-based providers are any professional or setting providing services in the community outside of the school or home, including clinical settings.

Providers

The most common professionals working with children and adolescents in Tennessee are described below:

- Pediatricians are community-based primary care providers and often the first health professional to see a child or adolescent experiencing mental health symptoms. Pediatricians can screen for mental health conditions and refer patients to specialists.(6)

- School Nurses in Tennessee provide medical care, promote a healthy school environment, offer health education programming, and coordinate health services for students. School nurses can screen students for mental and physical health conditions and refer them to early intervention and treatment services. (7)

- Mental Health Counselors/Therapists hold an advanced degree and provide treatment services for people with mental health conditions. A mental health counselor could be a licensed therapist, licensed social worker, or school counselor and provide services in schools, homes, and the community. (6)

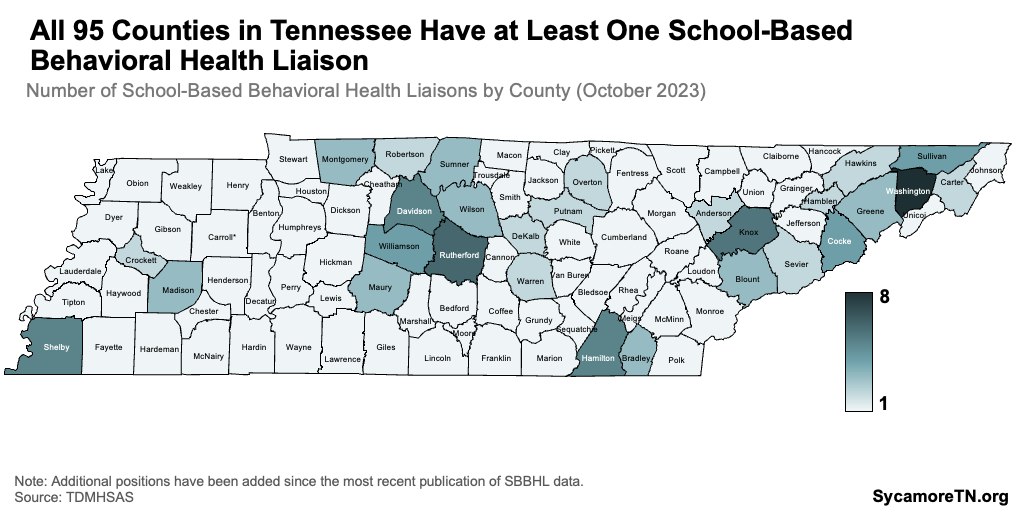

- School-Based Behavioral Health Liaisons (SBBHL) are employed by community mental health centers to provide services in schools. (8) Often, an SBBHL is a licensed therapist, social worker, or school counselor supported through TDMHSAS grants. While most liaisons provide Tiers I-II services, some also provide Tier III services. (9)

- Child Psychiatrists are physicians who have completed medical school and additional training in psychiatry. They may provide behavioral treatment and/or prescribe medications for individuals with mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety). Child psychiatrists most often provide services in schools or the community. (6)

- Child Psychologists have completed a Ph.D. or Psy.D. in clinical psychology. They may work with youth in schools or the community and in both inpatient and outpatient settings (e.g., with a child experiencing a psychiatric crisis in a hospital). (10)

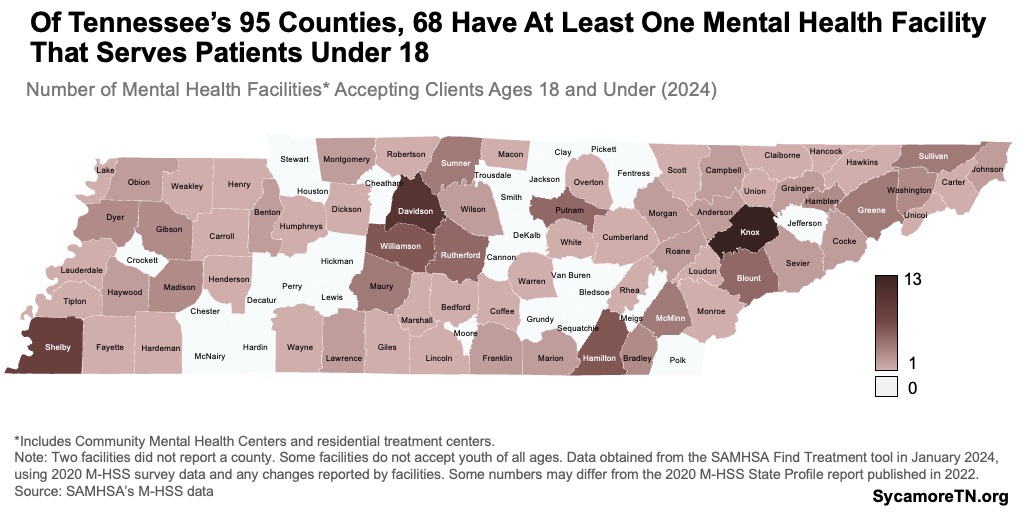

Figure 1

Settings

Agencies and organizations often work together to meet the mental health needs of Tennessee children. The settings in which a child might receive services include:

- Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) do prevention activities in a community and offer treatment services to people experiencing mental health and/or substance use challenges. They can also provide acute treatment to some who may otherwise need hospital-based care. (12) A CMHC must meet certain criteria for certification including personnel licensure, a set of required minimum services, and quality assessment and improvement activities. (13)

- Residential Treatment Centers are community-based residential treatment centers that provide care to individuals onsite, often for an extended time. Services are provided for individuals one-on-one, in groups, and with families and caretakers. (5) (4)

As of January 2024, Tennessee had 165 mental health facilities that accepted patients under 18 in 68 counties — including CMHCs and residential treatment centers (Figure 1). Some facilities do not accept young children and restrict services to older youth. According to a 2020 survey, most of Tennessee’s mental health facilities accept private insurance and Medicaid. (11)

- Crisis Stabilization Units (CSUs) provide acute, short-term community-based services to individuals experiencing a mental health emergency as an alternative to emergency departments. A CSU may offer individual and family counseling, medication management, individual treatment plans, education, and the development of a community support plan. Generally, a CSU is available 24/7, and patients stay an average of three days. (14) In Tennessee, the first children’s CSU opened in 2022 at the East Tennessee Children’s Hospital in Knox County through a federal grant awarded to the McNabb Center. (15)

- A Crisis Walk-in Center provides community-based, in-person evaluations for those experiencing a mental health emergency.(16) After receiving an evaluation at a walk-in center, an individual may be referred to services — including time in a CSU. (17) Tennessee has one walk-in center specifically for youth in Knox County.

- Hospitals provide community-based care to individuals in psychiatric crisis through emergency departments and inpatient stays greater than 24 hours. The length of treatment may depend on the individual’s needs and what community-based services are available upon discharge. (5)

- Provider Offices serve as the community-based clinical setting in which private mental health care professionals provide outpatient screening and treatment services. (5)

- Schools serve as critical touch points for reaching children and their families. Prevention, early intervention, and treatment services occur in schools, as described throughout this report. (2)

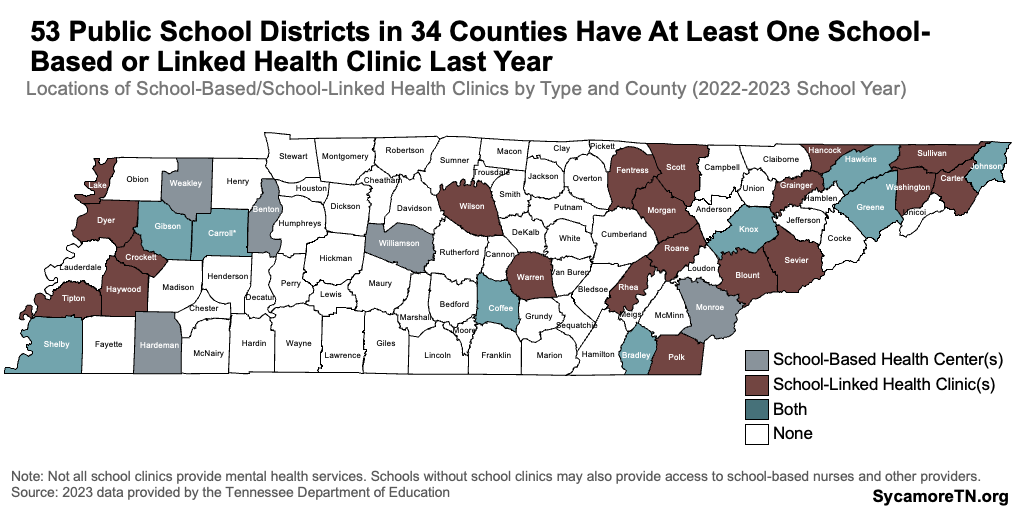

- School-Based Health Centers/School-Linked Health Clinics (SBHCs/SLHCs) employ health providers to offer services onsite, while SLHCs are a collaboration between a school and an external, community-based provider. (18) Both models serve students, staff, faculty, and family. In 2023, 53 school districts had at least one, but not all provide behavioral health services. (7)

- Homes can also serve as a setting for delivering services to children and their families. For example, the state’s home visiting program can do screening and provide early intervention services. Crisis response teams (often employed by a mental health facility) are dispatched to provide in-person assessments to individuals in acute need of care. (5) (19)

Overview

In general, school health programs, community mental health centers, and TennCare make up the state’s largest and most systemic strategies for child mental health, which are supplemented by other—often smaller—efforts that:

- Target specific concerns, priorities, populations, or regions (e.g., school safety).

- Bridge gaps between schools and community-based care (e.g., SBBHLs).

- Serve as a safety net for youth in crisis or with unmet needs (e.g., behavioral health safety net).

- Support mental health as a part of a broader set of services for a population (e.g., home visiting).

- Build infrastructure that can later be sustained through existing systems (e.g., AWARE).

- Fill other gaps and emerging needs (e.g., Systems of Care Across Tennessee).

Tennessee makes significant financial investments in these programs, but quantifying some of the state’s largest efforts is challenging. Large investments are made in programs like TennCare and Coordinated School Health. These are important avenues for promoting positive mental health, identifying children who may need early intervention, and providing treatment services, but estimates of the amounts spent on mental health-specific activities are not uniformly available. Based on available information, we estimate that a total of at least $330 million in FY 2022 was distributed as follows:[2]

- Crosscutting —Tennessee spent at least $24 million on youth-targeted mental health programs that address the full spectrum of prevention, early intervention, and treatment (e.g., Resilient School Communities, Tennessee Resiliency Project, school-based behavioral health liaisons, and AWARE). This does not include funding for TennCare and Coordinated School Health that also provide all tiers of services.

- Prevention — The state spent at least $6 million in FY 2022 on programs that primarily focus on prevention among youth (e.g. Project BASIC, child care consultation, suicide prevention). This does not include funding for mental health-specific prevention activities in the crosscutting programs above or TennCare (e.g., well-child visits), Coordinated School Health, and programs with a broader focus like Healthy Start and home visiting.

- Early Intervention — About $3 million went to targeted early intervention activities in FY 2022 (e.g. On Track TN, Regional Intervention Program). This excludes any funding for mental health-specific early intervention in the crosscutting programs above or TennCare, Coordinated School Health, Healthy Start, and home visiting.

- Treatment — In FY 2022, Tennessee spent at least $228 million specifically on treatment for youth through TennCare behavioral health treatment services and TDMHSAS’ Systems of Care Across Tennessee, behavioral health safety net for Children, and crisis services.

- Other Supports — The state spent about $17 million on other supports for youth mental health in FY 2022 like mental health workforce development and caregiver respite This does not include any funding for similar activities in the crosscutting programs above.

- Other Targeted — A total of about $51 million went to prevention, early intervention, treatment, and other supports for either the juvenile justice population or youth in the custody of the Department of Children Services.

Table 1

Tennessee’s Public Programs and Services for Child Mental Health

Crosscutting Programs and Services

Most of Tennessee’s programs addressing the full continuum from prevention to treatment are either school-based or involve a link between schools and community-based providers.

Crosscutting: TDOE School-Based Services

School districts primarily manage and offer mental health services through the Coordinated School Health (CSH) program. Supported by the Tennessee Department of Education’s (TDOE) Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement (TISA) — the state’s school funding formula — every school district is required to provide a common set of health services and develop plans to address their specific community needs. CSH has eight requirements, including:

- School counseling, psychological, and social services,

- Health education that covers mental health,

- Promoting a positive social climate, and

- Providing or facilitating access to health services. (20) (21)

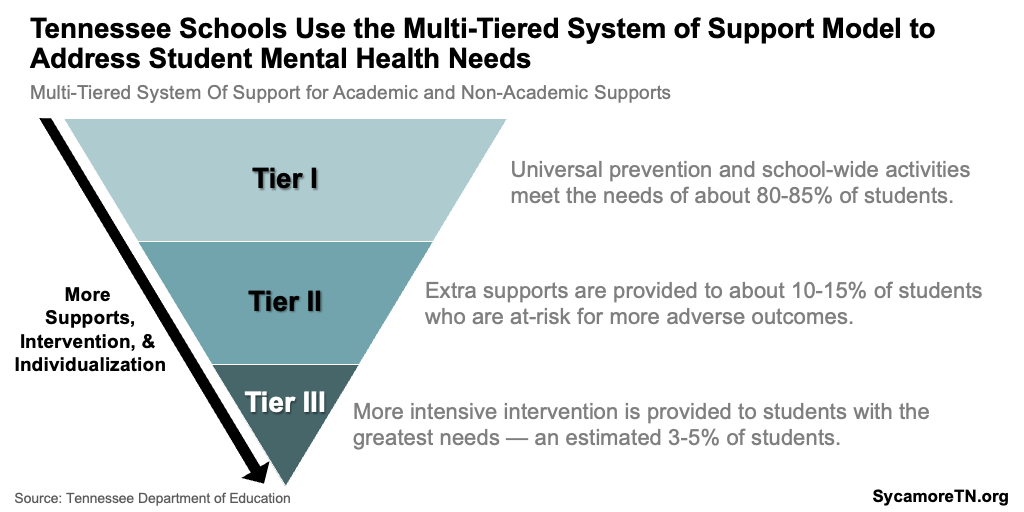

Figure 2

CSH’s school counseling, psychological, and social services component uses a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) framework to provide mental health services across the continuum (Figure 2). Under MTSS, universal prevention and school-wide programming is expected to meet the needs of 80-85% of students. A smaller group (10-15%) may need early intervention services to meet their needs, and those with intensive needs (3-5%) may receive treatment services at school or through a community-based provider. (20) For example:

- School nurses, counselors, and psychologists can screen students for mental health challenges.

- These school personnel can refer students with treatment needs to community-based providers.

- Some schools can provide needed services onsite under contracts with a school-based behavioral health liaison or other health provider, school-based health center, or school-linked health clinic.

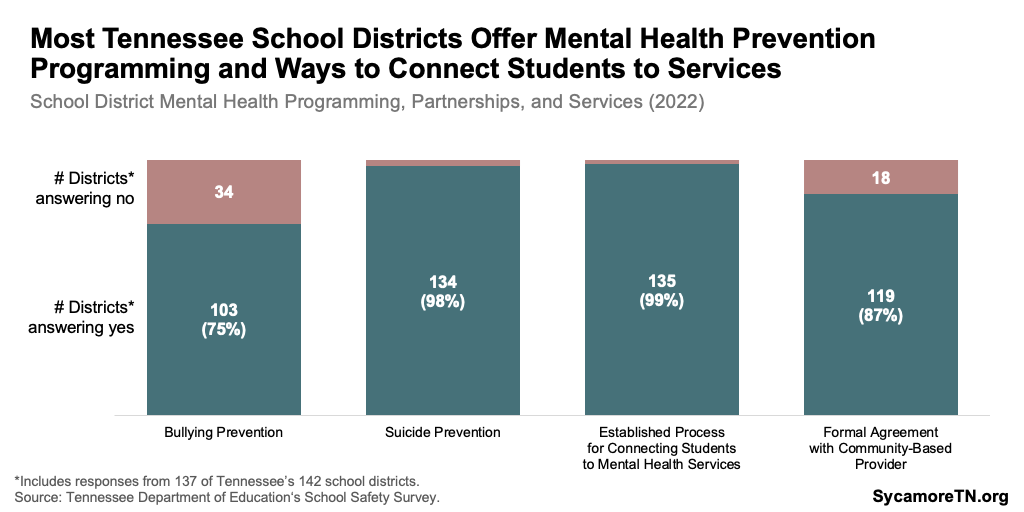

In 2022, most school districts reported having prevention programming and established processes for connecting students with mental health services. According to the 2022 Tennessee School Safety survey (Figure 3): (27)

- 75% of the 137 respondent districts had implemented a bullying prevention program.

- 98% conducted suicide prevention activities.

- 99% had an established process for connecting students to mental health services.

- 87% had a formal partnership with a community agency to provide services.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Crosscutting: TennCare

TennCare — the state’s Medicaid program — provides enrolled children with access to mental health prevention, early intervention, and treatment services in both schools and the community. Enrolled children receive well-child visits, which include screening and referrals for mental health conditions. TennCare also pays for inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceutical treatment and wraparound services like transportation and supported housing. Each of these are outlined in more detail later in this report.

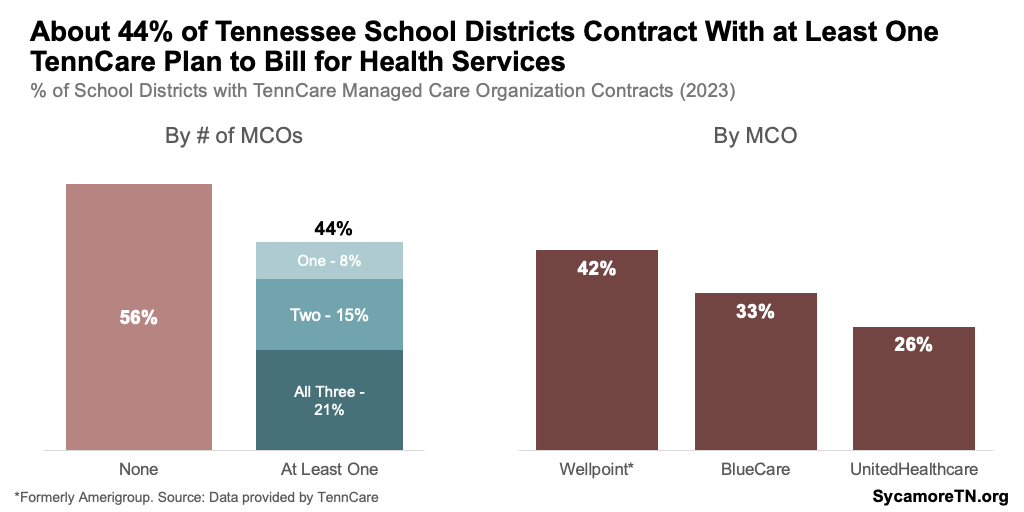

Some schools and providers can bill TennCare for behavioral health services provided to eligible children in schools. Three private health insurance companies, or managed care organizations (MCOs), administer TennCare benefits. MCOs reimburse school-based mental health services deemed medically necessary for eligible children. Community Mental Health Centers, individual mental health providers, and school districts can contract with MCOs for reimbursement. (29) (30) Among Tennessee’s 142 school districts, about 44% have contracted with at least one of TennCare’s three MCOs (Figure 5). (31) While TennCare MCOs will contract with any school district, they can use discretion in deciding to contract with a provider offering services in schools. (32)

TennCare pays for medically necessary, covered, school-based mental health services for certain children that have individualized plans for their academic achievement. Covered services must be included in an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), Individualized Health Plan (IHP), or Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). (25) IEPs primarily focus on special education services supporting students with disabilities — as required under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (33) (32) IHPs are a widely used tool for outlining needed medical services that directly affect learning but do not fall under an IEP. (34) An IFSP outlines early intervention services to support infants and toddlers with a physical disability or developmental delay. (35) (36)

Figure 5

Crosscutting: TDMHSAS

School-based behavioral health liaisons (SBBHLs) in every county provide all tiers of services within schools. TDMHSAS funds 274 SBBHLs across the state to provide prevention, early intervention, treatment, and referral services in schools. Liaisons can provide schoolwide educational activities, teach positive mental health to small groups, or provide individual counseling. As of 2023, every county, but not every school, had at least one school-based liaison (Figure 6). (8) Local school districts determine which schools receive a liaison. (38) TDMHSAS recently reported that $26.8 million supports the SBBHL positions across the state, and further expansions are proposed for FY 2025. (8) (39)

TDMHSAS’ Tennessee Resiliency Project supports local behavioral health providers, schools, and primary care providers in delivering youth mental health services. These grants promote early childhood mental health, increase access to school-based mental health services, and enhance the crisis continuum of care. In a previous funding announcement, grantees were encouraged to expand current programming, such as Project BASIC, the Regional Intervention Program (RIP), and SBBHLs. (40) (22) In 2023, funding was available to integrate behavioral health into primary care, such as co-locating therapists from CMHCs into primary care settings. (41)

In January 2024, TDMHSAS announced one-time K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund dollars to develop infrastructure to provide the full continuum of services. TDMHSAS considers project partnerships between community mental health providers and school districts for one-time activities supporting student mental health. Examples include renovating school space to accommodate counseling sessions, implementing educator training sessions, and purchasing behavioral health curricula. In total, $2 million recurring and $4 million non-recurring was made available from the fund for FY 2024 (see end of report). (42)

Figure 6

Crosscutting: Other TDOE Grants to School Districts

TDOE also distributes federal funds for specific mental health prevention and services initiatives. These include:

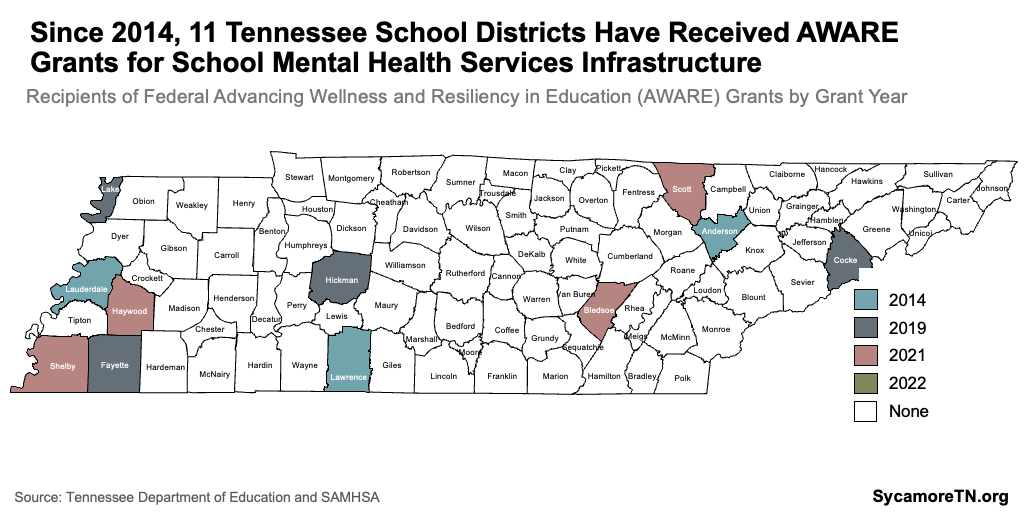

- Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education(AWARE) grants have been awarded to 11 Tennessee school districts since 2014 (Figure 7). Districts use grants to develop infrastructure for school-based mental health services and better coordination of referrals to community-based mental health services. (43) Tennessee AWARE recipients have, for example, used the funds to hire specialized personnel (e.g., student support specialists, project directors) and provide trauma-informed training for staff. (44)

- Safe Schools Act funding can be used to hire mental health staff and fund school safety initiatives — including facility security, school safety personnel, training, or drills.(45) In FY 2022, almost $1.6 million was allocated with an estimated 8% going towards mental health purposes. (23)

- Resilient School Communities grants were awarded to 97 school districts in 2022. Distributed through the state, funding totaled $10.2 million. (21) (46) The priorities of the grant include building resilient school communities by implementing trauma-informed practices, expanding current initiatives (e.g., AWARE grant activities), and increasing mental health staff capacity.

Figure 7

Tier I: Prevention Services

Tennessee’s targeted prevention efforts include statewide and regional programs that vary in who, how, and where they target children. Key efforts are highlighted below. See Appendix Table 1 for a more exhaustive list of programs.

- Primary Care Well-Child Visits include social, emotional, and behavioral screenings from birth through early adulthood usually by a child’s pediatrician. (47) Children with all insurance types can receive well-child visits to ensure they are meeting appropriate milestones and referred to needed services. A 2018 American Academy of Pediatrics review found that TennCare had adopted the full set of recommended services for well-child visits, including those related to mental health. (48)

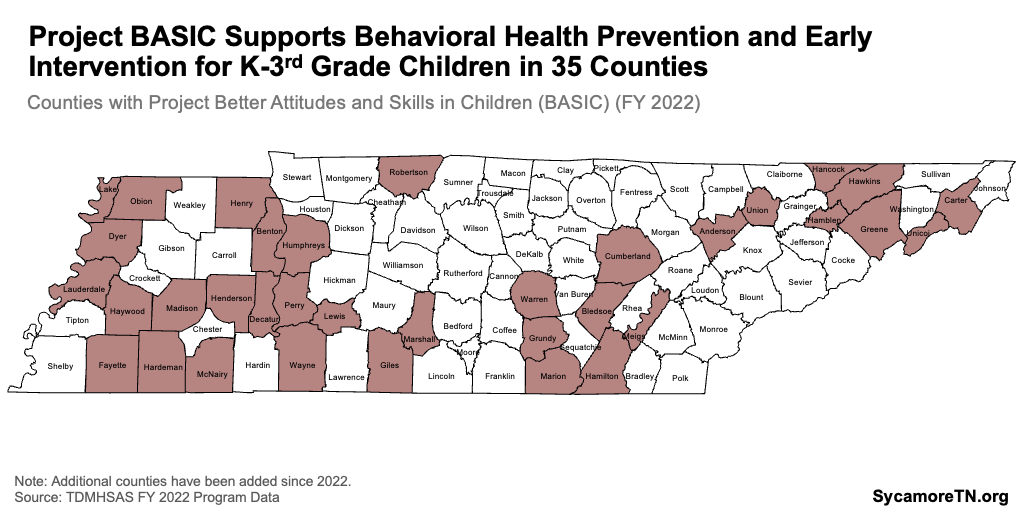

- TDMHSAS’ Project Better Attitudes and Skills in Children (BASIC) uses child development specialists to deliver school-based prevention and early intervention activities for about 1,000 elementary-aged children (K-3) in 35 counties (Figure 8). Using the MTSS model, CMHC-employed child development specialists carryout activities that support a positive school climate, consult with teachers and students, and identify children with serious emotional disturbance (i.e., a diagnosed mental condition that causes functional limitations). (3) In FY 2022, Project BASIC was funded at $1.8 million. (22)

- TDMHSAS’ Child Care Consultation provides training, coaching, and consultation to child care centers and systems across the state. This program builds capacity and awareness of early childhood mental health and social-emotional development. Child care consultation also provides Project BASIC training for child development specialists to incorporate mental health coaching into their practice. In FY 2022, the program reached 67 counties and served 654 individuals with a budget of $1 million. (49)

- TDMHSAS’ Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network (TSPN) increases awareness of suicide prevention through training and education. Nine regional councils across the state coordinate activities and disseminate information. (50) (51) The TSPN leads initiatives such as a suicide prevention task force and trainings for emergency departments. (51)

Figure 8

- TDMHSAS’ Erase the Stigma is a mental health awareness campaign to help children and youth understand mental and emotional well-being. The program primarily offers school-based presentations in Middle and West Tennessee, but the nonprofit Mental Health America’s Tennessee chapter provides the program in other settings by request.(22) In FY 2022, the program was funded at about $127,000 and reached around 13,500 Tennessee youth. (49)

- TDMHSAS’ Violence and Bullying Prevention serves 4-8th graders in schools in nine counties by teaching anger management, empathy, and self-control skills. (22) In FY 2022, this program spent $194,000 and reached 1,115 children. (49)

- TDMHSAS’ Youth Screen Assessment — or “Youth Screen” — is an online screening tool to detect signs of mental health risk among middle and high schoolers in schools and youth detention centers. Youth found to be at risk receive care coordination and referrals to appropriate resources. (22) (52) In FY 2022, Youth Screen was funded with about $300,000 in state and federal dollars, reaching about 2,000 middle and high schoolers in Tennessee. (22) (23)

- TDH’s Evidence-Based Home Visiting provides home-based prevention and early intervention services that promote positive family functioning, connection to resources, and safe and nurturing environments for kids.(25) In FY 2022, the program spent $2.7 million in state and federal dollars, reaching almost 2,500 youth. (23) (25)

Tier II: Early Intervention Services

Tennessee’s targeted early intervention programs support youth at risk of poor mental health. These programs help connect children and their families to resources to reduce the risk of developing adverse mental or physical health conditions. Key efforts are highlighted below. See Appendix Table 1 for a more exhaustive list of programs.

- TDMHSAS’ Regional Intervention Program (RIP) supports families with young children displaying difficult behaviors (e.g., aggression) by providing peer family support and education on parenting strategies. (22) In FY 2022, RIP was funded at $1.2 million by TDMHSAS and reached about 350 children in 11 counties.

- TDMHSAS’ On Track TN: Early Episode Psychosis Initiative targets individuals aged 15-30 in 21 counties who have experienced a first episode of psychosis (i.e., losing contact with reality — including hallucinations and delusions). (53) CMHCs often provide the services using training and technical assistance from Vanderbilt’s Center of Excellence. The initiative includes individual and group therapy, family and peer support, medication, care coordination, and employment and education services. (22) In FY 2022, the program was funded at $1.7 million and reached about 199 youth. (49)

Tier III: Treatment Services

Tennessee youth have access to a range of treatment services for mental health conditions — accessed at homes, schools, outpatient clinics, residential settings, and inpatient hospitals.

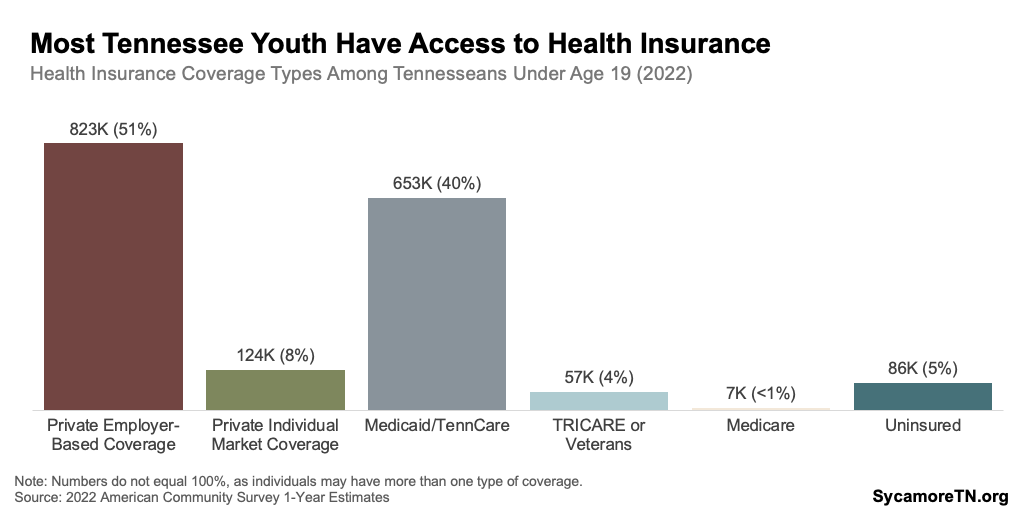

Tier III: Health Insurance and Clinical Services

Most behavioral health treatment services are provided in community-based clinical settings and covered by health insurance. In 2022, nearly 95% of Tennessee children and youth had some form of health insurance — with over half using private coverage and 40% covered by TennCare (Figure 9). (54)

Figure 9

Most health insurance plans are subject to state and federal mental health parity requirements. Under these requirements, most group health plans offering mental health coverage — including Medicaid programs — must do so at least as generously as services for physical health conditions. This applies to benefit packages, aggregate lifetime and annual dollar limits, treatment limitations, and financial requirements (e.g., copays). (55) A 2019 evaluation of these categories found that TennCare coverage met requirements across all areas. (56)

National studies suggest parity requirements have not closed disparities between behavioral and physical health benefit coverage. (57) In 2023, federal rules were proposed to strengthen parity requirements using several new metrics. The rules would give plans specific examples of how benefits regarding mental health and substance use disorder could not be more restrictive than that of other physical health services, such as network composition and reimbursement rates for providers. Additionally, the proposed rules require plans to analyze outcomes and take action to close gaps between mental health and substance use disorder services and other health services. A public comment period on the proposed rules closed in October 2023, and final rules have not yet been published. (57)

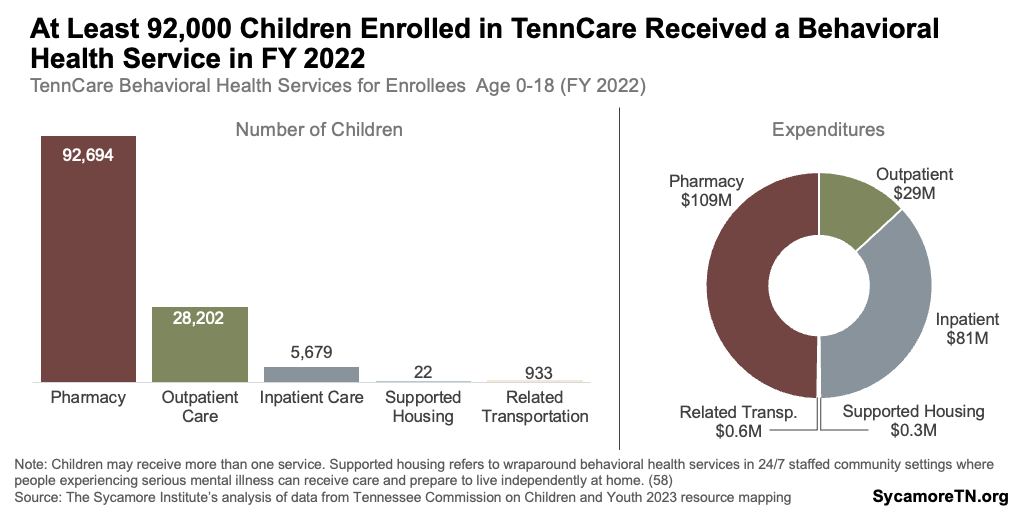

TennCare Coverage

In FY 2022, TennCare spent about $220 million on behavioral health services for at least 92,000 enrolled Tennessee youth (Figure 10). (37) Over 92,000 youth under the age of 19 received a prescription for a behavioral health condition, about 30,000 received outpatient services, and over 6,000 received inpatient services. Some children may have received more than one type of service. (37)

Figure 10

TennCare’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment program (EPSDT) also provides enrolled children access to mental health services. EPSDT is a set of comprehensive services that all state Medicaid programs must provide according to federal guidelines. Under EPSDT, children are regularly screened at provider visits from birth through age 21 for physical, developmental, and mental health conditions. (59) EPSDT also requires the coverage of treatment needed for any detected mental illnesses.

TennCare also provides targeted care coordination for enrollees with behavioral health conditions. As of 2022, child enrollees with certain behavioral health needs may enroll in one of two programs — Health Link or Intensive Community-Based Treatment. (60) Tennessee Health Link provides care management and coordination, referrals to social supports, patient and family support, and health promotion activities. Intensive Community-Based Support offers a more intensive level of care coordination, treatment and rehabilitation, crisis intervention, school-based counseling, and educational services. (61)

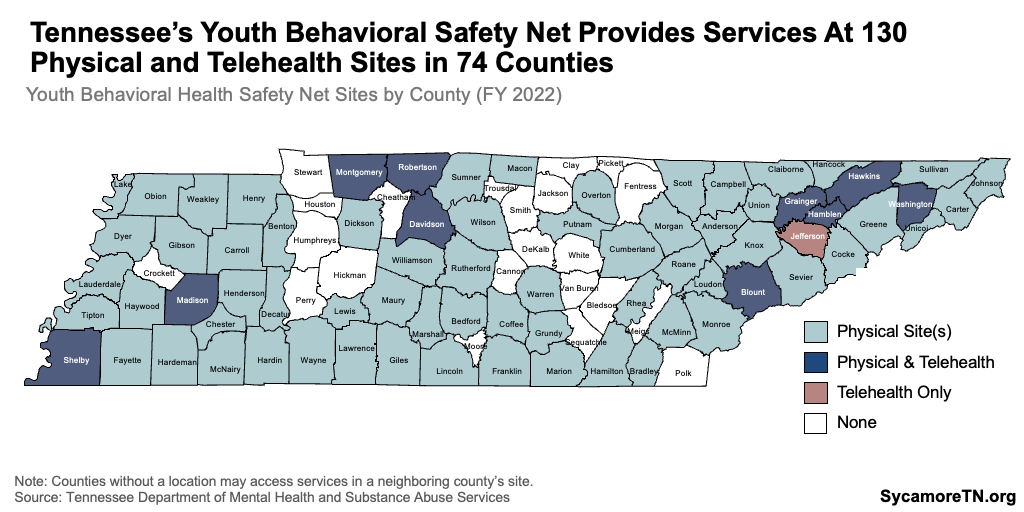

Tier III: Behavioral Health Safety Net

In FY 2022, approximately 1,100 children under 18 who were un- or underinsured received services from TDMHSAS’ behavioral health safety net. (62) The behavioral health safety net (BHSN) reimburses CMHCs for providing care to eligible children. To be eligible, a child must be at least three years old, have a qualifying mental health diagnosis, be a U.S. and Tennessee citizen, and have no other behavioral health coverage. (26) Children with CoverKids or private insurance may also enroll to receive limited services that may not be covered by their plan. The safety net includes 130 locations statewide at TDMHSAS-contracted community mental health centers. Most counties have access to at least one physical location (Figure 11). (26) In FY 2022, the BHSN spent $1.9 million on mental health services for children and adolescents. (23)

Figure 11

Tier III: Crisis Services

TDMHSAS supports a continuum of crisis services for youth. A youth experiencing a psychiatric crisis may have an acute change in behavior or thoughts — often putting them at risk to themselves or others. (63) The crisis continuum for youth includes call lines, mobile units provided by four CMHCs across the state, one walk-in center in Knox County, and one crisis stabilization unit (CSU) at Knox County’s East Tennessee Children’s Hospital. (17) (64) A national 988 line and Tennessee’s statewide 988-CRISIS-1 line can handle some cases over the phone and dispatch local providers when a face-to-face assessment is needed. (19) Mobile units help divert youth from emergency departments and inpatient hospitalizations.

In FY 2022, the state line fielded 126,000 crisis calls, and crisis mobile units and walk-in services provided over 12,000 face-to-face assessments. Of the calls, 53% were resolved over the phone, and the remainder were referred to mobile crisis services. (19) In FY 2022, state dollars funded mobile crisis services at $1.2 million. (62) (37) (65)

Tier III: Care Coordination

In FY 2022, TDMHSAS’ Systems of Care Across Tennessee (SOCAT) provided intensive care coordination for 225 children and young adults with serious mental health conditions. The program serves people age 21 and under whose conditions are affecting their daily lives or put them at risk for more serious consequences (e.g., being kicked out of school, needing residential treatment, Department of Children’s Services custody). (66) Providers offer services at 11 sites that serve all 95 counties. SOCAT principles emphasize family involvement and aim to keep children in their community. (67) (68) In FY 2022, TDMHSAS used $6.6 million to provide these services for 275 children and families. (49)

Tier III: Treatment for Special Populations

Tennessee funds treatment services for youth referred to juvenile court for behavior-related infractions. Several state and local agencies coordinate the program — including the Department of Children’s Services (DCS), TCCY, Tennessee Administrative Office of the Courts, juvenile judges, and court staff. Services include care coordination, family and group therapy, peer support, medication, substance use disorder services, and monitoring. (23) (22) State and federal funding for DCS juvenile justice treatment services totaled $9.5 million and served 1,285 youth and young adults in FY 2022.

TDMHSAS’ Juvenile Justice Grant seeks to expand the availability of community-based treatment options for juvenile courts across the state. The grant also supports educating professionals working in the juvenile justice system on trauma-informed approaches. In FY 2022, the program reached over 1,000 youth with a budget of $4.5 million. (49)

Treatment services are provided to youth in DCS custody or interacting with the foster care system. DCS programs include behavioral support, intensive family and group therapy, and parenting education classes. (23) The therapeutic family preservation home-based services under DCS cost $2.5 million and reached about 3,500 children and their families in FY 2022. (23)

Other Support Services

Other: Supporting the Behavioral Health Workforce

Available mental health treatments are only as good as the workforce delivering them, and the field faces challenges in Tennessee and nationally. (69) For example, geographic barriers and insurance coverage can limit access to specific providers, and primary care providers often face difficulty meeting their patients’ mental health needs. Some initiatives to address these challenges include:

- Behavioral Health Workforce Workgroup — In 2021, TennCare and TDMHSAS formed a workgroup to discuss behavioral health workforce challenges and potential solutions. This cross-departmental collaboration resulted in several recommendations to improve recruitment and retention of skilled, licensed professionals. (70) Examples of implemented recommendations include reimbursement rate increases, expanded internship opportunities, and planning for the workforce pipeline.

- Tennessee Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Education and Support (TCAPES) — In 2022, TDH received a $300,000 federal grant. (71) This grant supports the TCAPES program to help pediatricians better meet their patients’ mental health needs. Specifically, the program helps providers screen and manage pediatric behavioral health conditions and make specialist referrals. (24) Thirty-five primary care providers statewide had enrolled as of December 2023 (See Dashboard). (72)

- Project RAISE — In FY 2024, the TDOE will implement a $14 million federal grant for Rural Access to Intervention in School Environments (RAISE). (73) (74) Project RAISE will recruit and retain mental health personnel in rural school districts, in part by placing interns studying social work and psychology in these areas. Rural districts may use funds as a financial incentive for interns to relocate and work as full-time personnel after the internship.

Other: Practice Improvements

The state has focused on improving mental health care practices, especially by working to reduce emergency department admissions. Individuals in psychiatric crisis sometimes seek care at emergency departments (EDs). However, when possible, diverting individuals from EDs to community-based mental health facilities improves patient outcomes and reduces overcrowding in EDs. (75) Nationally, states are working to facilitate partnerships among providers to reduce ED admissions where possible.

In 2019, the Tennessee Hospital Association, Tennessee College of Emergency Physicians, and TDMHSAS convened a workgroup to identify ways to divert certain patients from the ED. (76) They identified protocols and resources for hospitals serving youth with mental health needs. Among several recommendations, they suggested an evaluation of provider reimbursement rates. Not all mental health providers contract with all insurance networks due to inadequate reimbursement rates. (77) Improving early access to care with broader provider networks can help reduce the number of individuals seeking care in crisis settings like EDs.

Other: Caregiver Support

Several state agencies provide support for caregivers of youth experiencing mental, emotional, and/or behavioral challenges. Examples include:

- TDMHSAS’ Statewide Family Support Network supports the families of children with serious emotional disturbance. Program specialists educate families about behavioral conditions, assist families in advocating for their child, and help navigate the education and health systems. (23)

- The Tennessee Commission on Aging & Disability’s Respite Program for Caregivers provides training, respite, and support for caregivers aged 55+ with children. In FY 2022, this program was funded at $203,000 with federal dollars and reached 184 children and their families. (37)

- TDMHSAS’ Planned Respite supports caregivers of children ages 2-15 with serious emotional disturbance with respite and educational strategies to manage the child’s behavior. In FY 2022, this program was federally funded at $427,000 and reached the caregivers of 94 children. (37)

- TDMHSAS’ Respite Voucher program provides vouchers for families whose children have serious emotional disorder or autism. Parents choose their respite provider, negotiate the pay rate, and receive reimbursement. Additionally, the Respite Helpline maintains a list of known respite providers across the state. In FY 2022, it served 336 children and their caregivers, totaling 11,677 respite hours with a $218,000 budget. (49)

- TDOE’s Youth Mental Health First Aid teaches participants how to support adolescents experiencing behavioral health challenges in crisis and non-crisis situations. (78) (21)

Recent Initiatives

Recent State Initiatives

State leaders have recently directed additional money and efforts to support child mental health — including investments in the proposed FY 2025 budget. Those being implemented are described throughout this report. Highlights include:

- K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund — In 2021, lawmakers created a $250 million K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund. Annual interest earned on the fund is used for mental health programming, including $6 million for TDMHSAS in FY 2024. (79)

- Behavioral Health Safety Net (BHSN) — In FY 2021, policymakers approved recurring funds to begin the BHSN for children, which provides outpatient mental health services for un- and underinsured children. (80)

- Increased Provider Reimbursements — In FYs 2023 and 2024, the state allocated $27 million in new recurring funds for reimbursement increases for behavioral health providers serving both TDMHSAS’ behavioral health safety net and TennCare. Higher provider reimbursements have helped improve recruitment and retention of behavioral health personnel. Gov. Lee proposed another $6 million recurring increase in the FY 2025 budget recommendation. (81) (39) (82)

- School-Based Behavioral Health Liaisons (SBBHLs) — Several recent funding increases have enabled the expansion of this TDMHSAS program to all 95 counties.(8) The FY 2025 Budget proposes an additional $8 million recurring increase for SBBHLs—including $6 million from the General Fund and $2 million from K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund earnings—to fund 114 additional school-based behavioral health liaisons.

- Crisis Stabilization Units (CSUs) — The McNabb Center established the first CSU specifically for adolescents in Knox County in 2022.(39) The FY 2025 Budget recommends $5 million non-recurring to fund the final year of a 2-year expansion of youth CSUs. (82)

- Children’s Hospital Infrastructure — In FY 2024, the budget includes $10 million in one-time funding for the first year of a 2-year grant program to develop behavioral health infrastructure at children’s hospitals. The FY 2025 recommendation includes $10 million for the second year. (82)

- School Safety Measures — During a 2023 special legislative session, policymakers enacted a $230 million school safety bill that included $8 million for school-based behavioral health.(83)

Other relevant proposals in the governor’s FY 2025 budget include (82):

- $15 million in FY 2025 and $30 million total through FY 2026 to support capacity and quality improvements at behavioral health hospitals.

- $7 million in FY 2025 and $35 million total through FY 2029 for quality incentive payments to community mental health centers and certain TennCare providers.

- $4 million non-recurring from K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund earnings to help localities expand capacity to provide school-based behavioral health treatment.

- $1 million in FY 2025 and $5 million through FY 2029 to provide in-home behavioral health support for infants and young children.

- $1 million in FY 2025 and $5 million total through FY 2029 to compensate behavioral health providers supervising trainees.

- $400,000 in FY 2025 and $2 million total through FY 2026 to train pediatric primary care providers to identify and manage behavioral health needs.

Recent Federal Initiatives

Federal officials have also recently launched new efforts around child mental health. For example:

- Bipartisan Safer Communities Act — A provision in this 2022 law directs the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to evaluate how states are implementing Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) program through 2024. The review is expected to include an emphasis on ensuring children with mental health conditions are accessing needed services. (84)

- School Technical Assistance Center — The U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services established a technical assistance center in 2022 to increase local schools’ capacity to provide school-based mental health services covered by Medicaid. (85)

- Project Rural Access to Interventions in School Environments (RAISE) — Project RAISE is a $14 million federal grant which began in FY 2024. Awarded to school districts through the TDOE, this grant aims to increase behavioral health capacity and the workforce pipeline. (73)

Explore the Data

Use the dashboard below to filter youth mental health resources by county and school district.

Parting Words

Tennessee has dozens of programs, large and small, spread across multiple agencies aimed at different aspects of children’s mental health. School health programs, community mental health centers, and TennCare comprise up the state’s largest and most systemic strategies and investments. Other, often smaller efforts tend to fill or bridge gaps in services and needs or target specific priorities or regions. Our next report in this series will identify potential opportunities for building on the state’s current efforts to improve child mental health.

[2] See the Appendix for our methodology.Note: This report was updated on February 19, 2025 to correct the number of agencies cited in the title of Table 1.

References

Click to Open/Close

- National Center for School Mental Health & University of Maryland School of Medicine. School Mental Health Quality Guide: Mental Health Promotion Services & Supports (Tier 1). [Online] 2020. https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/media/som/microsites/ncsmh/documents/quality-guides/Tier-1-Quality-Guide-1.29.20.pdf.

- University of Maryland School of Medicine. School Mental Health Quality Guide: Early Intervention and Treatment Services & Supports. National Center for School Mental Health. [Online] 2020. https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/media/SOM/Microsites/NCSMH/Documents/Quality-Guides/Early-Intervention-and-Treatment-Services-Guide-(Tiers-2-and-3)-2.18.pdf.

- The Pyramid Model Consortium. Tiers: General Overview. [Online] 2021. https://www.pyramidmodel.org/general-overview/.

- Youth Villages. How We Treat: We Believe Residential Treatment Should be Short Term. [Online] [Cited: December 6, 2023.] https://youthvillages.org/services/residential-services/.

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Continuum of Mental Health Care. [Online] September 2023. [Cited: December 6, 2023.] https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/The-Continuum-Of-Care-For-Children-And-Adolescents-042.aspx.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Mental Health Care Providers for Kids: Who’s Who. [Online] September 26, 2022. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/emotional-wellness/Pages/Mental-Health-Care-Whos-Who.aspx.

- Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE). Annual School Health Services Report: 2022-23 School Year. [Online] October 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/csh/Final_2022-23_Annual_School_Health_Services_Report.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). School-Based Behavioral Health Liaisons. [Online] [Cited: August 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/children-youth-young-adults-families/sbbhl.html#:~:text=School%2Dbased%20Behavioral%20Health%20Liaisons%20are%20employees%20of%20local%20community,district%20leadership%2C%20in%20identified%20schools.

- Information Provided. Information provided to The Sycamore Institute by UTK Mental Health Landscape Assessment Team. January 3, 2024.

- Cleveland Clinic. Child Psychologist. [Online] April 1, 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22666-child-psychologist.

- U.S. Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2020 National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) State Profiles Executive Summary. [Online] 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35984/2020%20N-MHSS%20State%20Profiles_FINAL.pdf.

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology: Community Mental Health Center. [Online] April 19, 2018. https://dictionary.apa.org/community-mental-health-center.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Community Mental Health Centers. [Online] September 6, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/health-safety-standards/certification-compliance/community-mental-health-centers.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Crisis Stabilization Units. [Online] [Cited: December 27, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/need-help/crisis-services/csu.html.

- McNabb Center. Children’s Crisis Stabilization Unit. [Online] [Cited: February 19, 2024.] https://mcnabbcenter.org/stories/childrens-crisis-stabilization-unit/.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Crisis Walk-In Centers. [Online] [Cited: February 5, 2024.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/need-help/crisis-services/walk-in-centers.html.

- McNabb Center. Family Walk-In Center. [Online] [Cited: February 19, 2024.] https://mcnabbcenter.org/#:~:text=The%20facility%20is%20open%20seven,(865)%20257%2D9982..

- Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE). Tennessee School Health Clinics: Best Practices and Strategies. [Online] May 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/csh/TN%20School%20Health%20Clinics%20Best%20Practices_Final.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Crisis Services for Children and Youth. [Online] [Cited: October 18, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/need-help/children-and-youth.html.

- Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE). Coordinated School Health. [Online] [Cited: November 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/education/districts/health-and-safety/coordinated-school-health.html.

- —. Comprehensive School-Based Mental Health Supports and Services. [Online] [Cited: September 30, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/education/districts/health-and-safety/school-based-mental-health-supports.html.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Services for Youth, Young Adults, and Families. [Online] [Cited: August 5, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/children-youth-young-adults-families.html.

- Tennessee Commission on Children & Youth (TCCY). Resource Map of Expenditures. [Online] 2023. https://www.tn.gov/tccy/programs0/resource-mapping-overview/map-reports.html.

- Tennessee Department of Health (TDH). About Tennessee Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Education and Support (TCAPES). [Online] [Cited: August 15, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/fhw/tcapes/about-tcapes.html.

- —. Evidence-Based Home Visiting. [Online] [Cited: October 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/fhw/tdh-ebhv.html.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Behavioral Health Safety Net for Children – Service Locations. [Online] [Cited: September 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/research/fast-facts/childrens-bhsn-locations.html.

- Tennessee Department of Education & Governor’s School Safety Council. 2022 TN School Safety Survey. [Online] November 2022.

- Information provided. Data provided to the Sycamore Institute by Tennessee Department of Education. 2023.

- TennCare. TennCare Billing Manual: Tennessee School Districts. [Online] July 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/SchoolBasedServicesBillingManual.pdf.

- Information provided. Information provided to the Sycamore Institute by TennCare Behavioral Health staff. December 2023.

- Information Provided. Data provided to the Sycamore Institute by TennCare. December 11, 2023.

- Information provided. Information on TennCare School-Based Services: Managed Care Oversight provided to the Sycamore Institute by TennCare’s School-Based Services Managed Care staff. November 2023.

- Mito Action. What Is an Individualized Healthcare Plan? [Online] 2009. https://www.mitoaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/What-is-an-Individualized-HealthCare-Plan-Kirsten-Casale.pdf.

- Heartland Regional Genetics Network. Individualized Healthcare Plans (IHP). [Online] [Cited: January 20, 2024.] https://www.heartlandcollaborative.org/ihp/.

- U.S. Department of Education. Sec. 303.344 Content of an IFSP. [Online] July 12, 2017. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/c/d/303.344#:~:text=The%20IFSP%20must%20include%20a,the%20information%20from%20that%20child%27s.

- Ritter, Laura. IEP and IFSP 101: Everything You Need to Now From Planning to Implementation. [Online] January 10, 2020. https://www.occupationaltherapy.com/articles/iep-and-ifsp-101-everything-5079-5079#:~:text=An%20IEP%20is%20an%20Individualized,until%20the%20child%27s%20third%20birthday.

- Information provided. Data provided to the Sycamore Institute by the Tennessee Commission on Children & Youth. July 26, 2023.

- —. Information provided to the Sycamore Institute by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services. October 18, 2023.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Fiscal Year 2024-2025 Governor’s Budget Hearing. November 15, 2023. Slide deck emailed to participants.

- —. Announcement of Funding: Tennessee Resiliency Project . [Online] October 8, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/documents/FY22_TN_Resiliency_Project_AOF.pdf.

- —. Announcement of Funding: Community Mental Health & Primary Care. [Online] April 20, 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/documents/MH_Primary_Care_Integration_AOF.pdf.

- —. Announcement of Funding: Announcement of Non-Recurring Funding for Infrastructure Grants. [Online] January 2024. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/documents/TDMHSAS_AOF_FY24_MHTF_Nonrecurring.pdf.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Project AWARE. SAMHSA. [Online] August 1, 2023. [Cited: October 1, 2023.] https://www.samhsa.gov/school-campus-health/project-aware.

- Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE). Tennessee Receives Nearly $4.7 Million Project AWARE Grant. [Online] November 5, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/education/news/2021/11/5/tennessee-receives-nearly–4-7-million-project-aware-grant-.html#:~:text=Nashville%2C%20TN%20%2D%20Today%2C%20the,Haywood%20County%20Schools%20and%20Scott.

- —. Safe Schools Act. [Online] [Cited: November 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/education/districts/health-and-safety/school-safety/safe-schools-act.html#:~:text=Safe%20Schools%20Act%20funds%20are,when%20such%20behavior%20may%20occur.

- —. Resilient School Communities Grant: Request for Applications (RFA). [Online] August 2022. https://mcusercontent.com/b28b453ee164f9a2e2b5057e1/files/1a480270-5336-0176-c70f-e515159dcf94/FSOW_RFA_Resilient_School_Communities_Grant_FINAL_Approved_08.15.2022_2_.pdf?mc_cid=200250f90a&mc_eid=502f6811d6.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Preventive Care/Periodicity Schedule. [Online] March 1, 2023. https://www.aap.org/periodicityschedule.

- —. Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT)- Tennessee. [Online] March 2018. https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/CHIP%20Fact%20Sheets/EPSDT_state_profile_tennessee.pdf.

- Information provided. Updated FY 2022 program data provided to the Sycamore Institute by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services. February 8, 2024.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network. [Online] [Cited: September 28, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/need-help/suicide-prevention/tspn.html#:~:text=TSPN%20is%20a%20statewide%20public,and%20individuals%20with%20lived%20experience.

- Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network. Resources. [Online] [Cited: September 28, 2023.] https://tspn.org.

- TN Voices. Let Go of the Stigma. Help is Here. [Online] [Cited: September 1, 2023.] https://tnvoices.org.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). On Track TN: First Episode Psychosis Initiative. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/children-youth-young-adults-families/on-track-tn.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. [Online] September 2023. http://www.data.census.gov.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). CMS.gov. [Online] September 6, 2023. [Cited: November 1, 2023.] https://www.cms.gov/marketplace/private-health-insurance/mental-health-parity-addiction-equity.

- TennCare. Mental Health Parity in the TennCare and COVER Kids Program. [Online] September 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/MentalHealthParity.pdf.

- U.S. Federal Register. Requirements Related to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act: A Proposed Rule by the Intenal Revenue Service, the Employee Benefits Security Administration, and the Health and Human Services Department. [Online] August 3, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/08/03/2023-15945/requirements-related-to-the-mental-health-parity-and-addiction-equity-act.

- Amerigroup. Tennessee Medicaid Housing Service Programs Utilization Management (UM) Guideline. [Online] December 27, 2019. https://provider.amerigroup.com/docs/gpp/TN_HousingServicesRevisedGuidelines2019.pdf?v=202012020013#:~:text=Supported%20Housing%20(SH)%20services%20are,to%20live%20in%20community%20settings.

- TennCare. Rules of The Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration: Bureau of TennCare. [Online] April 2023. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/rules/1200/1200-13/1200-13-13.20230419.pdf.

- —. Behavioral Health Services Webinar. [Online] [Cited: December 10, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/BHServicesUpdatesRateIncreases.pdf.

- —. Care Coordination Service Overlap – Supplemental Information . [Online] June 2022. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/CCSOProviderSupplementalInformation.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). TDMHSAS Fast Facts. [Online] April 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/documents/TDMHSAS_Fast_Facts_2023.pdf.

- Wheat, Santina, Dschida, Dorothy and Talen, Mary. Psychiatric Emergencies. Primary Care. [Online] June 2016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27262012/#:~:text=Psychiatric%20emergencies%20are%20acute%20disturbances,or%20others%20from%20imminent%20danger.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Infographic: Tennessee’s Mental Health Crisis Services Continuum. [Online] 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/documents/Crisis_Continuum_Outcomes_FY22.pdf.

- Information Provided. Information provided to the Sycamore Institute by TennCare. February 9, 2024.

- Tennessee Systems of Care. Services. [Online] [Cited: January 17, 2023.] https://socacrosstn.org/services/.

- Tennessee Commission on Children & Youth (TCCY). Council on Children’s Mental Health. [Online] [Cited: September 28, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/tccy/programs0/ccmh-home.html.

- —. February 2009 Report to the Legislature. [Online] January 30, 2009. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tccy/documents/ccmh/ccmh-report09.pdf.

- Counts, Nathaniel. Understanding the U.S. Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage. The Commonwealth Fund. [Online] May 18, 2023. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2023/may/understanding-us-behavioral-health-workforce-shortage.

- TennCare & Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services. Public Behavioral Health Workforce Workgroup: Strategies for Meeting the Need in our Communities. [Online] December 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/documents/2021_Public_Behavioral_Health_Workforce_Workgroup_Report.pdf.

- U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA). FY 2022 Pediatric Mental Health Care Access (PMHCA) Awards. HRSA Maternal and Child Health. [Online] May 2023. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/programs/pediatric-mental-health-care-access/fy-2022-pediatric-mental-health-care-access-awards.

- Information provided. TCAPES enrollment data provided to the Sycamore Institute by the Tennessee Department of Health. December 21, 2023.

- Owens, Mye. Project RAISE Aims to Fill Mental Health Gap in Rural TN School Districts. WKRN. [Online] September 1, 2023. https://www.wkrn.com/news/local-news/project-raise-aims-to-fill-mental-health-gap-in-rural-tn-school-districts/.

- Wagner, Stephanie. State, MTSU School Counseling Coordinator Partners on $14M Grant to Serve Rural Communities. Middle Tennessee State University. [Online] July 31, 2023. https://mtsunews.com/project-raise-state-partnership-counseling/.

- Hodge, Michael A, et al. Emergency Department Use by Children and Youth with Mental Health Conditions: A Health Equity Agenda. Community Mental Health Journal. [Online] January 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8762987/.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services & Tennessee Hospital Association. Tennessee’s Public-Private Psychiatric Delivery System: A Joint Plan of Action. [Online] August 2019. https://tha.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-ED-Boarding-Report-Final-With-Appendices.pdf.

- Government Accountability Office (GAO). Mental Health Care: Access Challenges for Covered Consumers and Relevant Federal Efforts. [Online] March 29, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104597.

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing. Mental Health First Aid for Youth. [Online] [Cited: November 15, 2023.] https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/population-focused-modules/youth/.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code 49-3-502 – K-12 Mental Health Endowment Fund. [Online] https://casetext.com/statute/tennessee-code/title-49-education/chapter-3-finances/part-5-k-12-mental-health-trust-fund-act/section-49-3-502-k-12-mental-health-endowment-fund#:~:text=The%20K%2D12%20mental%20health,secondary%20schools%20in%20this%20state.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). TDMHSAS Expands Behavioral Health Safety Net to Children. [Online] September 10, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/news/2020/9/10/tdmhsas-expands-behavioral-health-safety-net-to-children.html.

- —. 2022 Needs Assessment Summary Multiple Needs by Region Department Update. [Online] [Cited: December 11, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/mentalhealth/planning/2022%20NA%20Summary%20Multiple%20Needs%20Department%20Update.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. The Budget: Fiscal Year 2024-2025. [Online] February 2024. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/2025BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- Jones, Vivian. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee Signs $230M School Safety Bill: Here’s What It Does. The Tennessean. [Online] May 10, 2023. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2023/05/10/tennessee-gov-bill-lee-signs-230m-school-safety-bill/70202938007/.

- Burak, Elizabeth Wright. Bipartisan Safer Communities Act Provision Directs CMS to Review State EPSDT Implementation, including in Managed Care. Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy Center for Children and Families. [Online] July 27, 2022. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2022/07/27/bipartisan-safer-communities-act-provision-directs-cms-to-review-state-epsdt-implementation-including-in-managed-care/.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Technical Assistance Center (TAC). [Online] 2022. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/medicaid-state-technical-assistance/medicaid-and-school-based-services/technical-assistance-center-tac/index.html.

- Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE). Family Resource Centers Annual Report: 2022-2023. [Online] 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/special-education/frc/FRC_Annual_Report_2022-23Final.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Health (TDH). About Community Health Access and Navigation in Tennessee. [Online] [Cited: October 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/fhw/mch-cyshcn/chant/about-chant.html.

- —. Child Health and Development (CHAD) Program. [Online] [Cited: November 1, 2023.] https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/fhw/mch-cyshcn/chant/chad.html.