Medical debt is surprisingly common and can have far-reaching economic effects. This report explores how medical debt occurs. A companion report looks at the estimated prevalence of medical debt in Tennessee and explains why it matters. Future reports will focus on how medical debt varies across Tennessee’s 95 counties and options for policymakers who want to address it.

Key Takeaways

- Medical debt is unique from other types of debt for its connection to health-related circumstances that individuals often cannot predict or control.

- When medical bills go unpaid, they are often sold to debt collectors and can be reported to credit bureaus.

- If reported to a credit bureau, debt can hurt a person’s credit score, which lenders, employers, utilities, and others use to gauge financial reliability.

- Medical bills can also become debt when paid with loans, which may accrue higher costs than the original bill.

Acknowledgement: This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.

Sycamore takes a neutral and objective approach to analyze and explain public policy issues. Funders do not determine research findings. More information on our code of ethics is available here.

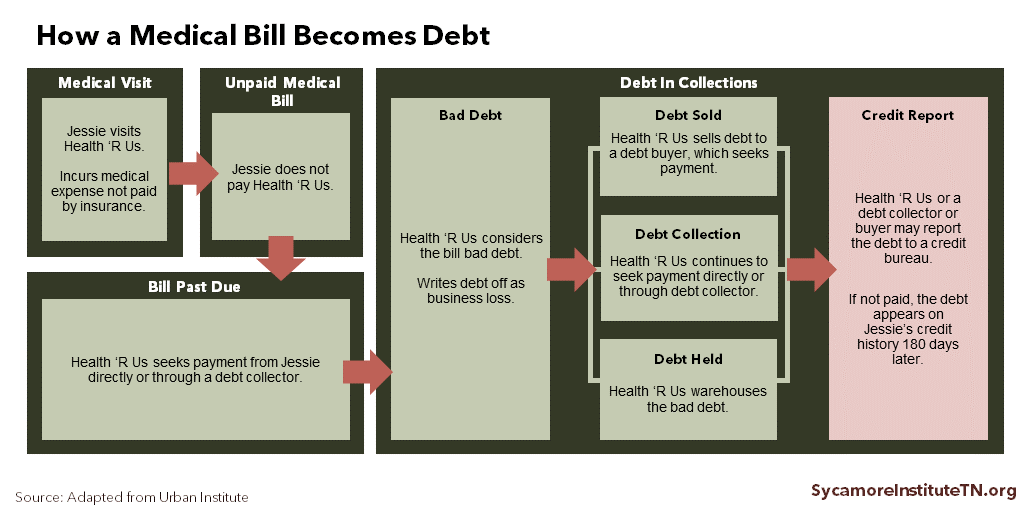

Figure 1

The Path from Medical Bill to Medical Debt

An unpaid medical bill follows the path to debt much like other types of bills (Figure 1). However, medical debt is unique among various types of debt for its connection to health-related circumstances that individuals often cannot predict or control (e.g. an accident, insurance claim denial, surprise medical bill).

Unpaid Medical Bill

If a person does not pay a medical bill, the health care provider attempts to collect the money either directly or through a contracted bill collector. Several unique features of the health care financing system contribute to medical bills going unpaid (see “The Unique Causes of Medical Debt”). Federal law requires certain steps by nonprofit hospitals and most federally-qualified health centers to determine a patient’s eligibility for financial assistance and how much they can be charged. (2) (3) (4)

Bill Past Due

The provider considers a bill past-due if the patient does not either pay it or arrange a payment plan. On average, hospitals and health care providers usually expect to receive payment within 90-180 days of billing a patient, but there is no defined amount of time that a provider must wait before considering a bill past due. (5) (6) (7) In 2017, Tennessee hospitals reported $1.5 billion of “bad debt” — i.e. past-due medical debt they considered a business loss. (6) To help offset these costs, some hospitals get supplemental payments from Medicare and the state’s Medicaid program, TennCare. (8) (9)

Debt in Collections

Providers can turn an unpaid bill over to in-house or third-party debt collectors or sell it to a debt buyer. Debt buyers usually purchase debts for a small fraction of the debt amount. Debt collectors and buyers typically seek payment with letters and phone calls and may charge penalties and interest. If the debt remains unpaid, however, they may also file civil lawsuits that can lead to outcomes like garnished wages or personal property seizure. (10) (11)

Credit Scores

An unpaid medical bill can be reported to credit bureaus at any point after the bill is issued. (7) If it is reported to a credit bureau and not paid within 180 days of that report, the debt appears on a credit report as an “account in collections.” (12) In 2014, medical debt accounted for 52% of all accounts in collections nationwide. (7) Not all unpaid medical bills or debts in collections are reported to credit bureaus.

Collections accounts on an individual’s credit report hurt their credit score. If unpaid medical bills are reported to a credit bureau, that person’scredit score is reduced for seven years — even if they ultimately pay off the debt. (6) Consumers can improve their credit scores by making on-time payments for most debt types (e.g. a mortgage and credit cards). Credit bureaus do not track on-time medical bill payments, however, so medical bills can only reduce a person’s credit score. (13) (14)

Lenders use credit to gauge an individual’s liabilities and the probability that they will pay their financial obligations. Credit scores can be a gateway or a barrier to financial stability and economic mobility:

- Access to “Good” Debt — Lower credit scores can make it harder to access the types of loans and credit that can enhance economic mobility and long-term wealth (see text box). (15) (16)

- The Cost of Debt — A good credit score allows people to qualify for loans with better interest rates. In August 2018, a person with good credit could have paid $3,000 less in interest on a $10,000 car loan than someone with a poor credit score. (17)

- Employment Opportunities — Many employers check credit reports when making hiring and promotion decisions. (18) A 2017 national survey of employers found that over 30% checked credit history in making employment decisions. (19)

- Housing Opportunities — Credit scores can determine a person’s ability to secure a mortgage as well as the terms of their loan. In addition, landlords often check potential tenants’ credit reports, and they may reject applicants for poor credit history or require a larger security deposit. (18)

- The Cost of Transportation & Utilities — Credit history can also affect basic needs like transportation and utilities. Car loans can be more expensive or unattainable for those with poor credit, and utility companies (e.g. water, electricity, internet, cable) may require larger security deposits from new customers with poor credit. (18)

- The Cost of Insurance — Credit history can also affect home, auto, and life insurance premiums. To protect Tennesseans, state law forbids insurers from considering medical debt for this purpose. (20) (21)

Since 2017, medical debts in collections can be removed from credit reports if the insurer ultimately pays a disputed or overdue bill. (12) However, if the patient is ultimately responsible for any portion of the bill after a dispute is resolved, the debt remains on their credit history even if they pay it in full.

Good vs. Bad Debt

Different types of debt are often described as being “good” or “bad.” The precise definitions of each category may depend on the source, but in general:

- “Good” (i.e. secured) types of debt can help the borrower build wealth, earn more, or become more financially secure. Examples commonly include home mortgages, student loans, and small business loans.

- “Bad” (i.e. unsecured, high-cost) types of debt are often associated with negative financial outcomes. Examples commonly include credit card debt, medical debt, car title loans, and payday loans.

“Bad” debt for one person may not be “bad” debt for everyone. While credit card debt is usually considered “bad,” using a credit card responsibly can improve a person’s credit score and help them secure better loan terms in the future. On the other hand, if a person consistently maintains a high credit card balance and is unable to make payments, their credit score will suffer. (16)

Medical debt does not always accurately reflect one’s will or ability to pay. (13) (22) A 2014 study by the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that half of people with medical collections had an otherwise clean credit history. (23) One reason may be bills sent to collections for reasons other than willingness or ability to pay (see “The Unique Causes of Medical Debt”). As a result, some entities that evaluate credit information (e.g. credit bureaus, lenders, employers) now exclude medical collections when reviewing credit histories. (13) (22) However, excluding medical debt is not a required or widespread practice.

Taking Loans to Pay Medical Bills

Medical bills can also become debt when people take loans to pay them, often at higher cost. To pay their bills, people sometimes use credit cards, take out a second home mortgage, or turn to other higher-cost forms of credit. (15) (5) For example, a 2016 Kaiser Family Foundation national survey found that 34% of people who reported problems paying medical bills increased credit card debt to help pay them. (24) In the 2015 National Financial Capability Study, an estimated 50% of Tennesseans with unpaid medical bills (compared to 23% without) reported taking a payday loan (i.e. a short-term, high-interest loan) in the last five years. (25) Interest and late fees that accrue from these financing mechanisms can sometimes cost more than the original bill.

The Unique Causes of Medical Debt

Medical debt is unique from other types of debt due to some of the ways in which people can end up with an unpaid medical bill — including the complexity of medical billing, third-party reimbursement process, and the unpredictable nature of health care costs. (23) (26)

Unpredictable or Unaffordable Health Care Costs

Health care needs are not always predictable. In the 2016 Kaiser survey, 66% of people who reported a problem paying medical bills attributed it to an unexpected, short-term medical expense like an accident. (24) Unexpected illness or injury can also reduce a family’s income and ability to pay for needed medical care. When unexpected illness strikes, the patient (and sometimes a family member/caretaker) may have to stop working or cut their hours. (5)

People without health insurance are more likely to have unpaid medical bills, but cost-sharing and surprise bills mean insurance is not a cure-all. Most health insurance offers financial protection against catastrophic medical expenses. However, an insured person may still get bills they do not expect or cannot afford. These bills can reflect cost-sharing requirements (e.g. deductibles, co-pays, and co-insurance), services not being covered, or providers being out-of-network. (27) (24) (28) (29) For example, a patient at an in-network hospital who unknowingly gets care from an out-of-network provider could receive an unexpected bill from that provider (also called a “balance bill”). (30)

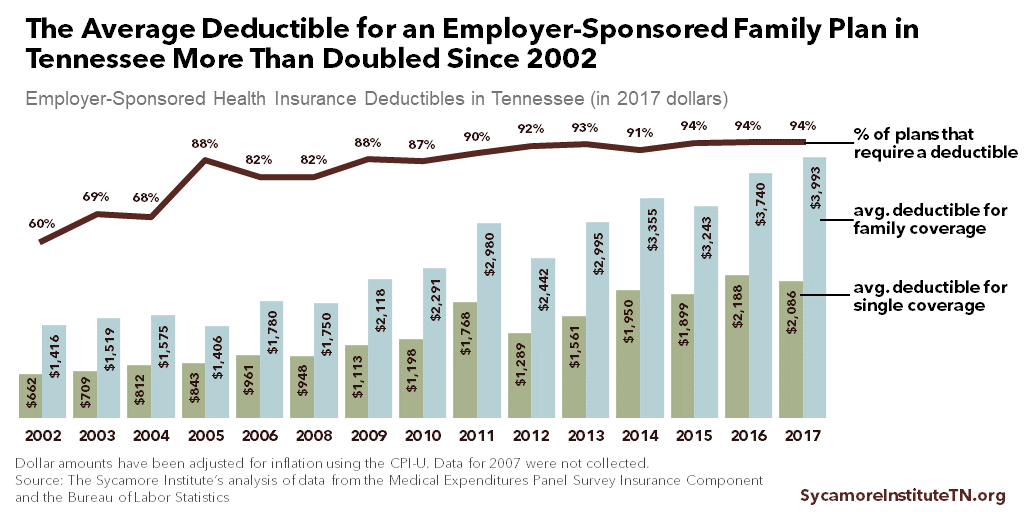

Almost every employer-sponsored insurance plan in Tennessee now requires a deductible, and the average family plan deductible has nearly tripled since 2002 (Figure 2). Almost half of Tennesseans got their health insurance plans through an employer in 2017. (31) That same year, 94% of employer plans in Tennessee required an out-of-pocket deductible — up from 60% in 2002. Over the same period, the average deductible for family coverage grew 2.8 times larger, after accounting for inflation. (32) (33)

Figure 2

The price of health care services is not always clear. Patients are typically responsible for out-of-pocket costs not covered by insurance but often do not know the price of medical care before it is provided. (34) (35) The price of care can also depend on coverage. For example, insured consumers often pay based on rates negotiated by their insurer and the provider, while uninsured, self-paying consumers are often charged more. (36)

Complexity of Medical Billing

The complexities of medical billing also contribute to medical debt. The medical billing process involves complicated interactions between patients, health care providers, and insurance companies. Any confusion or error in those interactions can lead to unpaid bills.

Billing errors and disputes between providers and insurers can result in unpaid medical bills. For example, one study found healthcare.gov Marketplace insurers in Tennessee denied between 8% and 23% of claims by in-network providers in 2017. (37) These disputes can delay or deny payment to providers for services provided to patients. Reasons that a claim may be denied include:

- Billing mistakes — Insurers may not provide prompt payment to health care providers if the providers do not properly bill insurers. For example, a provider may fail to include required prior authorization paperwork or use the wrong billing codes. (26)

- Medical necessity determinations — Insurance companies may deny a claim when they disagree with a health care provider about whether the service was medically necessary or appropriate. (13)

Patients are often asked to pay disputed medical bills while insurers and providers attempt to resolve the dispute. If an individual does not pay the bill during this time, it can be turned over to collections. Before receiving medical care, most consumers sign consent forms agreeing that they are responsible for any medical bills their insurance company does not cover in full. (13)

A few reasons related to the complexities of medical billing that patients might not pay their bills include:

- Confusion about billing — Consumers may have trouble differentiating between a bill and an explanation of benefits from their insurer, as well as whether to pay their provider or insurance company. (26) (23)

- Being unaware of a debt — Due to billing errors or miscommunication, consumers may not realize a bill is past-due or has been turned over to collections. (38)

- Awaiting dispute resolution — Patients may choose not to pay their bill until after any billing errors or disputes have been resolved.

Parting Words

Medical debt is a complex topic with far-reaching implications for Tennesseans’ health and prosperity. This report and a companion report kick off a series that we hope will inform an evidence-based discussion about medical debt in Tennessee, its effects, and potential policy levers. Subsequent reports will explore county-level data on medical debt in Tennessee and options for policymakers who want to address it.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Braga, Breno, et al. Local Conditions and Debt in Collections. Urban Institute. June 2016. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/81886/2000841-Local-Conditions-and-Debt-in-Collections.pdf.

- U.S. Code. Consolidated Health Centers Act – Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act Statutory Language. February 10, 2018. http://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Section-330-statute-as-of-March-2018-Clean.pdf.

- James, Julia. Health Policy Brief: Nonprofit Hospitals’ Community Benefit Requirements. Health Affairs and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. February 25, 2016. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20160225.954803/abs/.

- 111th U.S. Congress. The Affordable Care Act – Public Law 111-148 (Section 9007). March 23, 2010. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- Pollitz, Karen and Cox, Cynthia. Medical Debt Among People with Health Insurance. Kaiser Family Foundation. January 7, 2014. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/report/medical-debt-among-people-with-health-insurance/.

- Tennessee Department of Health. Joint Annual Report of Hospitals: Hospital Summary Report for 2017. December 3, 2018. Accessed on February 4, 2019 from https://apps.health.tn.gov/publicjars/default.aspx.

- Stone, Corey. Here’s How Medical Debt Hurts Your Credit Score. U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. December 11, 2014. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/heres-how-medical-debt-hurts-your-credit-report/.

- Tennessee Division of TennCare. TennCare II Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration. October 23, 2018. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/tenncarewaiver.pdf.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). Payment Basics: Hospital Inpatient Services Payment System. October 2018. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/payment-basics/medpac_payment_basics_18_hospital_final_v2_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- Federal Trade Commission. Repairing a Broken System: Protecting Consumers in Debt Collection Litigation and Arbitration. July 2010. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-bureau-consumer-protection-staff-report-repairing-broken-system-protecting/debtcollectionreport.pdf.

- American Civil Liberties Union. A Pound of Flesh: The Criminalization of Private Debt. [Online] 2018. https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/022318-debtreport_0.pdf.

- Andrews, Michelle. Medical Debt? Big Changes are Coming to the Way Credit Agencies Report It. Kaiser Health News. July 2017. https://www.statnews.com/2017/07/11/credit-score-medical-debt/.

- Rukavina, Mark. Medical Debt and Its Relevance When Assessing Creditworthiness. Suffolk University Law Review. January 2014. [Cited: December 4, 2018.] http://suffolklawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Rukavina_Lead.pdf.

- Wu, Chi Chi. Strong Medicine Needed: What the CFPB Should Do to Protect Consumers from Unfair Collection and Reporting of Medical Debt. National Consumer Law Center. September 2014. http://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/report-strong-medicine-needed.pdf.

- Seifert, Robert W and Rukanina, Mark. Bankruptcy Is the Tip of a Medical-Debt Iceberg. Health Affairs, 25(2): W89-W92. 2006. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.25.w89.

- Expanding Prosperity Impact Collaborative (EPIC). Consumer Debt: A Primer. The Aspen Institute. March 2018. http://www.aspenepic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Consumer-Debt-Primer.pdf.

- Elliot, Diana and Lowitz, Ricki Granetz. What is the Cost of Poor Credit? Urban Institute. September 2018. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99021/what_is_the_cost_of_poor_credit_1.pdf.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Consumer’s Guide: Credit Reports and Credit Scores. https://www.federalreserve.gov/creditreports/pdf/credit_reports_scores_2.pdf.

- HR.com. National Survey: Employers Universally Use Background Checks to Protect Employees, Customers, and the Public. National Association of Professional Background Screeners. June 2017. https://pubs.napbs.com/pub.cfm?id=6E232E17-B749-6287-0E86-95568FA599D1.

- Commissioners, National Association of Insurance. Credit-Based Insurance Scores: How An Insurance Company Can Use Your Credit to Deterimine Your Premium. June 2012. https://www.naic.org/documents/consumer_alert_credit_based_insurance_scores.htm.

- State of Tennessee. TN Code § 56-5-202(3)(E) (2017). https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2017/title-56/chapter-5/part-2/section-56-5-202/.

- Avery, Robert B, Calem, Paul S and Canner, Glenn B. Credit Report Accuracy and Access to Credit. Federal Reserve Bulletin. [Online] Summer 2004. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2004/summer04_credit.pdf.

- U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Consumer Credit Reports: A Study of Medical and Non-Medical Collections. December 2014. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201412_cfpb_reports_consumer-credit-medical-and-non-medical-collections.pdf.

- Hamel, Liz, et al. The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation. January 2016. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/8806-the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundation-new-york-times-medical-bills-survey.pdf.

- The Sycamore Institute. Analysis of 2012 and 2015 National Financial Capability Study. FINRA Investor Education Foundation. Accessed from http://www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads.php.

- Kurani, Nisha. Medical Debt and Hospital Charity Care Policies: A Case Study. 2017. http://www.heraca.org/documents/working%20papers/Nisha%20Kurani%20Advanced%20Policy%20Analysis-Medical%20Debt%20&%20Hospital%20Charity%20Care%20Policies_A%20Case%20Study.pdf.

- Karpman, Michael and Caswell, Kyle J. Past-Due Medical Debt Among Nonelderly Adults, 2012–15. Urban Institute. 2017.https://www.urban.org/research/publication/past-due-medical-debt-among-nonelderly-adults-2012-15.

- Cousart, Christina. Answering the Thousand-Dollar Debt Question: An Update on State Legislative Activity to Address Surprise Balance Billing. National Academy for State Health Policy.April 2016. https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Surprise-Balance-Billing.pdf.

- Mcelwee, Sean. Enough to Make You Sick: The Burden of Medical Debt. Demos. 2016. https://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Medical%20Debt.pdf.

- Adler, Loren, et al. State Approached to Mitigating Surprise Out-of-Network Billing. USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy. February 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/State-Approaches-to-Mitigate-Surprise-Billing-February-2019.pdf.

- American Community Survey via the Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population (2017). 2018.https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – Insurance Component State and Metro Area Tables. 2003-2018. Accessed on February 4, 2019 from https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/quick_tables_search.jsp?component=2&subcomponent=2.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.Historical Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U): U.S. city average, all items, index. December 2018. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/supplemental-files/historical-cpi-u-201812.pdf.

- Expanding Prosperity Impact Collaborative (EPIC). Lifting the Weight: Solving the Consumer Debt Crisis for Families, Communities & Future Generations. The Aspen Institute Financial Security Program. 2018. http://www.aspenepic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/LiftingtheWeight_SolutionsFramework.pdf.

- Doty, Michelle M, et al. Seeing Red: The Growing Burden of Medical Bills and Debt Faced by U.S. Families. The Commonwealth Fund. August 2008. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2008_aug_seeing_red__the_growing_burden_of_medical_bills_and_debt_faced_by_u_s__families_doty_seeingred_1164_ib_pdf.pdf.

- Reinhardt, Uwe. The Pricing of U.S. Hospital Services: Chaos Behind A Veil of Secrecy. Health Affairs, 25(1): 57-69. 2006. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3970/35599ac25f6ad5fbed72d635aac08517a8bf.pdf.

- Pollitz, Karen, Cox, Cynthia and Fehr, Rachel. Claims Denials and Appeals in ACA Marketplace Plans. February 25, 2019. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/claims-denials-and-appeals-in-aca-marketplace-plans.

- U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Data Point: Medical Debt and Credit Scores. May 2014. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201405_cfpb_report_data-point_medical-debt-credit-scores.pdf.

Featured image at top by Pictures of Money