Tennessee has made progress in reducing the supply of prescription opioids by targeting efforts to improve provider prescribing practices and reducing the number of pill mills. The opioid epidemic is evolving, however, and opioid- and heroin-related hospitalizations and overdoses continue to rise. Addiction, a chronic brain disease, is behind many of these trends and is one of the root causes of the epidemic. (1)

Reducing the demand for opioids will involve a comprehensive and coordinated spectrum of efforts to promote health and well-being, prevent substance abuse and opioid misuse, and treat drug addiction.

The third installment of our 3-part series on the opioid epidemic, this report examines the environment for preventing and treating addiction in Tennessee and provides examples of additional strategies that could help prevent opioid misuse and improve Tennesseans’ access to evidence-based addiction treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Tennessee’s capacity for addiction treatment is lower than the demand and out of sync with the geography of the opioid epidemic.

- Coverage and payment practices by private insurers, TennCare, and the state’s safety net influence treatment capacity and individuals’ access to treatment.

- Assessing current practices and additional strategies may require a comprehensive, multi-stakeholder review that includes the state’s public and private payers.

The Substance Abuse Prevention Environment in Tennessee

Both health promotion and addiction prevention efforts include activities that are typically “upstream” where they address the drivers of health. Prevention efforts target the risk factors and protective factors associated with drug addiction and abuse. Substance abuse prevention has evolved over the years from “Just Say No” and the fried egg analogy to efforts that focus on the often complex underlying issues.

Examples of Existing Efforts

Tennessee’s Building Strong Brains initiative aims to address adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and other sources of childhood toxic stress that are risk factors for substance abuse. These efforts help build resilience — a protective factor against addiction — during early childhood and adolescence, a critical time for human brain development.

A network of county-level drug-free coalitions spearheads community-based prevention efforts in Tennessee. Overseen by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS), the number of state-funded coalitions in the network increased from 34 to 43 in 2016. In addition to coordinating events to take-back unused or expired medications, these coalitions also engage youth in drug-free efforts and coordinate anti-drug billboards. (3)

Opioid-specific prevention efforts include the “Take Only As Directed” ad campaign encouraging Tennesseans to only take opioid medications in accordance with doctors’ orders. (4) Policymakers in Michigan, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and South Carolina are considering requiring mandatory opioid abuse education in public schools. (5)

Tennessee has enacted a number of policies to limit the supply of prescription opioids, which is an important part of preventing opioid abuse and addiction. In recent years, Tennessee has adopted nearly all best practices by expanding the use of its controlled substance monitoring database (CSMD), publishing prescribing guidelines, and regulating pain management clinics.

Examples of Other Strategies

Tennessee could further integrate ACEs into substance abuse prevention efforts by:

- Collecting ACEs data at the county level,

- Increasing the awareness of ACEs among health care providers and the social service workforce, and

- Accounting for ACEs as a primary risk factor when planning for substance abuse prevention efforts. (2)

Improved data sharing and collaboration could help Tennessee better target its efforts to prevent opioid misuse. A majority of Tennessee’s opioid overdose data come from hospitals and death certificates, and the lag time can be months or years. Access to real-time data and full use of existing datasets across both public health and law enforcement could improve prevention efforts. For example, other states are:

- Integrating CSMD data with other data. Integrating CSMD data with electronic health records, health information exchanges, and pharmacy dispensing systems can increase convenience for prescribers and dispensers and provide access in real time.(6) Texas, Kansas, Washington, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, West Virginia, Maine and Florida are testing this type of integration. (7)

- Using EMS data. Emergency medical services (EMS) data are geocoded and real-time. As a result, they are often more current than other data sources and can help identify hotspots for targeted prevention activities. (8) In New Orleans, the Health Department and EMS collaborate and share data to combat opioid overdose. (9) Trinity Emergency Medical Services in Massachusetts has also used technology to share EMS data with first responders, law enforcement, and public health officials. (10)

- Collaborating across sectors. Greater collaboration and data-sharing across law enforcement, human services, and public health can improve prevention messaging and the use of data and trends to target prevention efforts. (6)

The Treatment and Recovery Environment in Tennessee

Effective treatment and recovery programs often include medically-assisted detoxification, counseling, and medications that are tailored to individual needs.

Screening and Referral to Treatment and Recovery

Tennessee has undertaken targeted efforts in recent years to increase screening for substance use disorder (SUD) and to expand opportunities to refer individuals with SUD to treatment.

Examples of Existing Efforts

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is an evidence-based early intervention tool that allows primary care providers to quickly identify and address substance misuse among their patients. Federal funding to increase the use of SBIRT across the country have focused on training providers and residents to integrate it into their current and future medical practices. With funding from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), TDMHSAS has funded over 43,000 SBIRT screenings in Tennessee between October 2011 and March 2017. (11)

A state law enacted in 2017 aims in part to connect intravenous drug users to treatment. SB 806 / HB 770 (Public Chapter 413) allows the Tennessee Department of Health to approve non-governmental entities to operate evidence-based syringe exchange programs. (12) Syringe exchange programs in other states have proven effective at both preventing HIV and connecting intravenous drug-users to treatment. (13)

Examples of Other Strategies

Other strategies being used or recommended nationally seek to connect individuals to treatment and recovery services in the wake of an overdose. For example, the National Governors Association (NGA) recently recommended that states train first responders in referring patients to treatment options and establish peer-based recovery programs in emergency departments. (6)

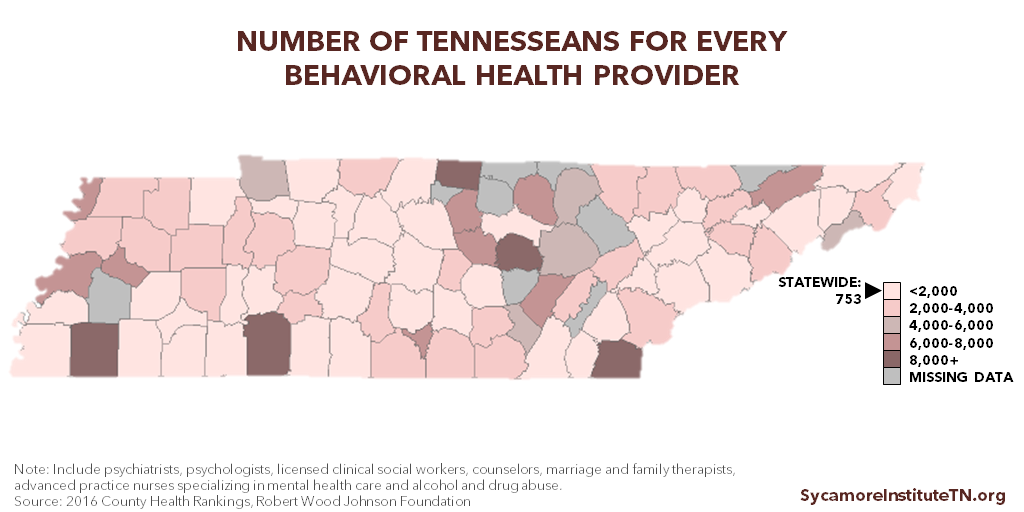

Figure 1

Treatment Provider Capacity

Treatment is only available to the extent that providers and services exist and are accessible to the individuals who need them. In 2016, an estimated 61% of Tennessee’s need for behavioral health providers went unmet. (14) The ratio of residents to behavioral health providers in Tennessee is 753:1 but varies greatly within the state (Figure 1).

TDMHSAS oversees the state’s behavioral health capacity planning through statewide and regional policy and planning councils. In TDMHSAS’ most recent needs assessment, the councils identified the following treatment and recovery capacity needs: Recovery housing, residential treatment beds, detox, recovery support services for adolescents transitioning from outpatient treatment, community-based services, and care management. (15)

Examples of Existing Efforts

To increase access to recovery services, Tennessee has focused on the state’s faith community and peer support groups. In 2013, Tennessee launched the Faith-Based Recovery Network to engage faith-based organizations in increasing recovery services capacity. Since that time, TDMHSAS have certified 180 faith-based recovery organizations to provide recovery services. (11) The state has also increased funding for Lifeline Peer Groups, allowing the number of meetings held each year to increase from 61 in 2013-2014 to over 100 in both 2014-2015 and 2015-2016. (11) (16)

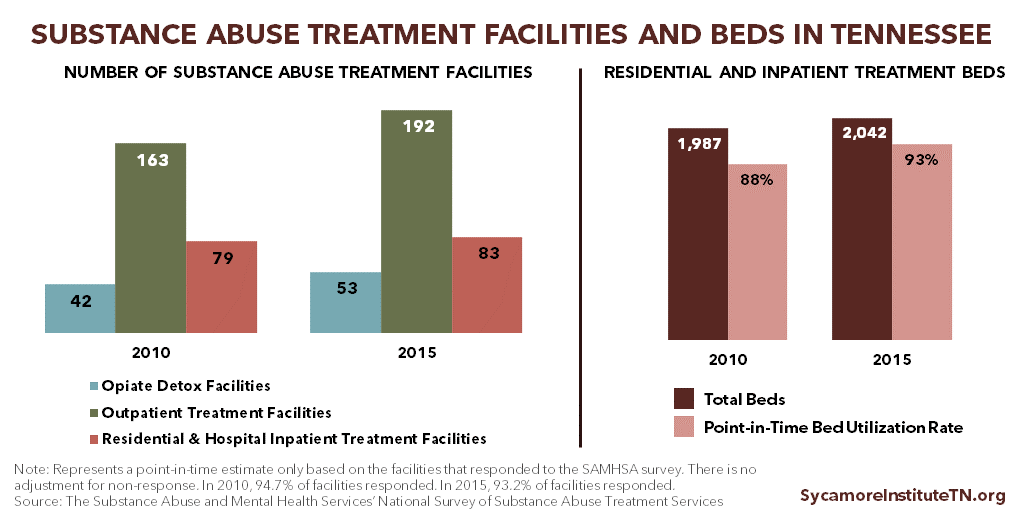

Figure 2

Examples of Other Strategies

Increasing the pipeline of providers and addressing coverage practices, restrictions, and payments that affect provider incentives may help increase treatment capacity. Steps other states have taken include: training stipends, loan repayment programs, internship and mentoring opportunities, more higher education funding for mental health and addiction fields, early recruitment of students to the field of addiction medicine during K-12 education, and bringing payment for behavioral health services in line with physical health services. (17)

Addressing coverage and payment policies may require a comprehensive review in collaboration with the state’s public and private payers. Additional coverage-related options are discussed throughout this report.

Reducing the stigma associated with addiction can also increase access to treatment services. The National Governors Association (NGA) recommends that states develop public awareness campaigns that recognize SUD as a chronic disease with effective treatment options available. (18)

Medication-Assisted Treatment Capacity

Research has found that a combination of counseling and medication — known as medication-assisted treatment (MAT) — is the most effective approach for opioid addiction.

Examples of Existing Efforts

Tennessee faces challenges with the availability and distribution of MAT across the state. The state has 12 licensed opioid treatment programs (OTPs) that can provide methadone and 649 licensed buprenorphine providers (as of May 2017). Only 3 of the 12 OTPs are located east of Nashville — 2 in Knoxville and 1 in Chattanooga. Another 3 are in Memphis, where prescription opioid abuse rates are lower than many other parts of the state. (19)

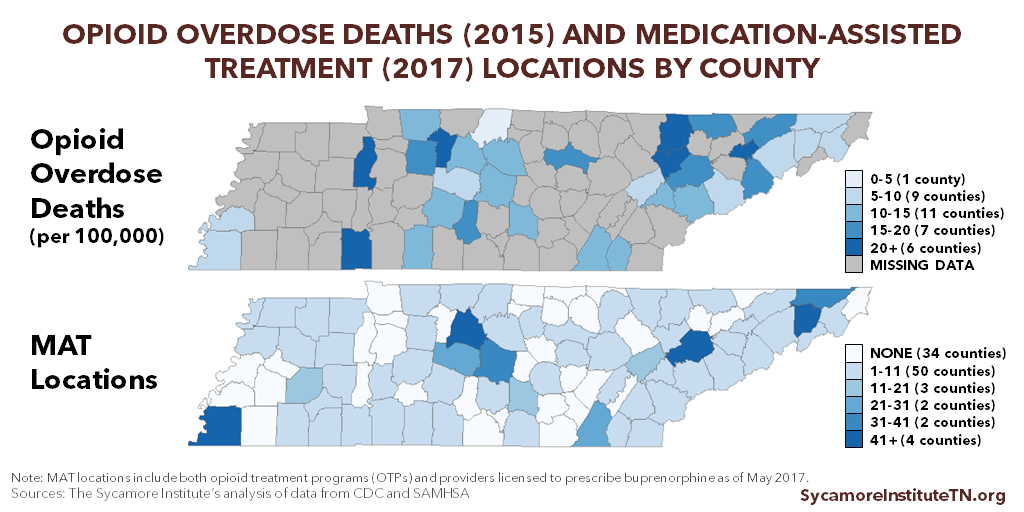

Figure 3 shows the distribution of opioid overdose deaths in 2015 alongside the distribution of locations currently certified to provide methadone and/or buprenorphine. At least 3 counties (Benton, Cheatham, and Marshall) had 15 or more overdose deaths per 100,000 residents but zero MAT locations. Opioid overdose death rates were not available for 61 of Tennessee’s 95 counties.

Figure 3

Less than half of Tennesseans with opioid dependence have ready access to buprenorphine treatment based on the number of physicians certified to provide it, according to a 2015 analysis. (20) Although Tennessee has a higher buprenorphine treatment capacity than most other states (21), a 2017 county-by-county analysis of buprenorphine providers and rates of opioid misuse by TDMHSAS found that:

- 50 counties had less than 85% of the potential need for buprenorphine met,

- 9 counties had 85-115% of need met, and

- 36 counties had over 115% of need met. (22)

Examples of Other Strategies

Several targeted strategies being advanced nationally might help to expand MAT capacity in Tennessee:

- To expand access to MAT, the federal government authorized nurse practitioners and physician assistants to prescribe buprenorphine in 2016. Tennessee law explicitly bars all providers except physicians from prescribing buprenorphine. (26) (27) (28)

- NGA suggests one way to increase access to MAT is by requiring buprenorphine waiver training in certain state medical residency programs. (29)

- NGA also recommends that state Medicaid programs cover all approved MAT medications. (6) Some critics of TennCare’s decision to stop covering methadone in 2005 (more details below) claim it has limited the number of opioid treatment programs available — particularly in northeast Tennessee. (30)

Substance Abuse Treatment Safety Net

Federal, state, and local governments fund services for certain low-income adults who are otherwise unable to access or afford needed substance abuse recovery and treatment services. These publicly funded services are often referred to as the safety net.

Examples of Existing Efforts

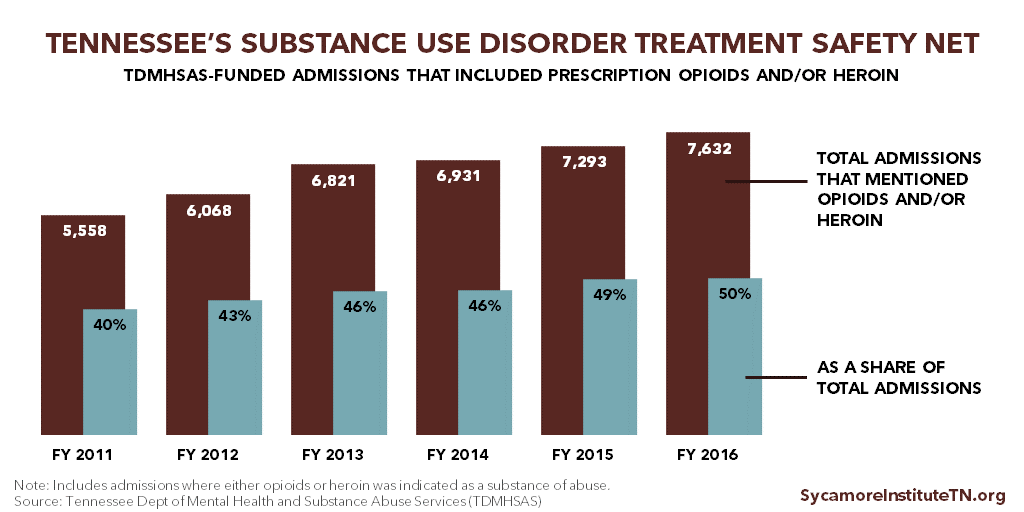

TDMHSAS supports safety net substance abuse recovery and treatment for adults with incomes below 133% of the poverty level and with no access to other sources of coverage (e.g. TennCare, employer-provided health insurance). Between 2011 and 2016, the number of total treatment admissions funded by TDMHSAS increased by 10%, from 14,000 to nearly 15,400. Admissions for opioids and/or heroin abuse increased by 37%, from about 5,500 to 7,600 (Figure 4).

Figure 4

These increases, however, do not match increases over the same time period for opioid misuse outcomes (e.g. 60% increase neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) cases (31) (32), 70% increase in opioid- and heroin-related hospitalizations (33), 44% increase in overdose deaths associated with all opioids (including heroin)). (34) In 2016, the top treatment services funded by TDMHSAS were residential treatment, halfway houses, and intensive outpatient care. (35)

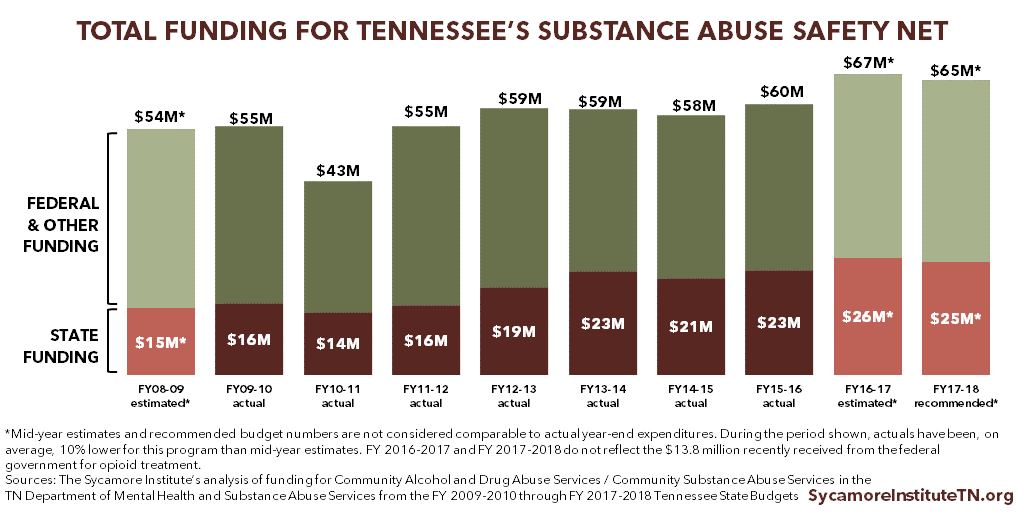

Figure 5 shows total estimated funding for TDMHSAS’ Community Substance Abuse Services since FY 2010-2011. The most recent budget for FY 2017-2018 includes $6 million in recurring funding to provide treatment services for an additional 2,000 individuals. (36) (37)

In addition, Tennessee is slated to receive at least $13.8 million in one-time funding over 2 years to expand opioid treatment via the 21st Century Cures Act passed by Congress in 2016. Tennessee was awarded $13.8 million of this funding in April 2017, and additional funding is expected in 2018. TDMHSAS will use these funds to expand MAT, treatment services for pregnant women, treatment in rural areas, and recovery support services. TDMHSAS has not yet released estimates of how many additional individuals they will be able to serve with these dollars. (38)

Figure 5

Examples of Other Strategies

Tennessee policymakers should closely track how well investments from state and federal sources meet treatment needs — in terms of both reaching more low-income people and achieving individuals’ treatment goals. Despite the recent increases in the number of individuals misusing opioids served by TDMHSAS, unmet need remains. According to a 2014 TDMHSAS estimate, about 10,000 individuals below the poverty level were in need of state-funded treatment for prescription opioid addiction. The unmet funding need to treat all of these individuals totaled about $29 million. (39)

TDMHSAS does not publicize waitlist estimates, but a 2016 audit found that the wait time for a detox bed can be weeks. (40) New funding increases should help meet some of this need, but it will be important to track this progress and to plan for a transition when one-time federal dollars are no longer available. It will also be important to study the long-term outcomes of individuals who participate in TDMHSAS-funded treatment.

TennCare

Certain low-income individuals rely on Medicaid (known as TennCare in Tennessee) for insurance coverage of needed treatment services. Even before the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, Medicaid was the 2nd largest payer nationally for SUD treatment behind publicly-funded safety net and criminal justice-related programs. (41)

Examples of Existing Efforts

TennCare covers behavioral health crisis services and medically necessary inpatient and outpatient SUD treatment services. (42) TennCare also covers naltrexone and buprenorphine with prior authorization. It covers methadone only for those under age 21. TennCare does not currently cover methadone for other enrollees. (43) (44)

TennCare plays a role in providing access to health care including addiction services for young pregnant women with opioid addiction in particular. TennCare is the primary payer for NAS cases in Tennessee, and in 92% of those cases, the mothers were covered by TennCare during their pregnancies. (45)

In 2017, the General Assembly passed legislation that requires TennCare managed care organization (MCOs) to begin reporting on their coverage practices for mental health and SUD services. Reports will include whether and how often MCOs use prior authorization for these services and medications compared to other services and medications. (46)

Examples of Other Strategies

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have encouraged states to use Medicaid as a tool to address the opioid epidemic. According to CMS, coverage restrictions and requirements like prior authorization may reduce access to MAT. (47) NGA recommends that state Medicaid programs cover all approved MAT medications and remove barriers like prior authorization. (6)

Additionally, TennCare does not cover inpatient addiction treatment in certain facilities, which may limit access to treatment and residential treatment capacity in the state. Medicaid prohibits addiction treatment for non-elderly adults in facilities with more than 16 beds. Intended to limit the use of mental health institutions, the rule has also impacted the number of inpatient beds available for low-income individuals who need drug treatment. In 2015, CMS encouraged states to apply for waivers from the rule to expand Medicaid-funded treatment options for opioid abuse. (48) A number of states have applied for the waiver. To date, TennCare has not. (49)

In 2016, the state’s 3-Star Healthy Task Force proposed to cover low-income adults with behavioral health needs via TennCare as a way to address the opioid epidemic and reduce criminal justice costs. An estimated 64,000 low-income, uninsured Tennesseans had SUDs in 2013. (50) TennCare eligibility expansion could increase access to addiction treatment services for many of these individuals. States that have expanded Medicaid have seen an 18% reduction in unmet need for addiction treatment services among low-income adults. (51) The task force’s proposal is on hold while Congress considers legislation to roll back or repeal the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion.

Private Health Insurance

What and how private insurers cover addiction services can influence enrollees’ access to treatment and the larger health care system’s capacity to provide treatment. The majority (58%) of non-elderly Tennesseans get health insurance from a private insurer. (52)

Examples of Existing Efforts

Some evidence suggests MAT usage may be lower among privately insured Tennesseans who abuse opioids than those in other states. According to the Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) Association of America, Tennesseans covered by BCBS in 2016 had higher rates of diagnosed opioid use disorder than did BCBS enrollees in any other state. Of these, only 32% received MAT — compared to a national average of 37%. (53) BCBS of Tennessee is the state’s largest health insurer in all markets covering 77% of Tennesseans in the large group market (which includes most employer-provided health plans). (54) (55) (56)

Federal law requires equal coverage for addiction treatment, but public awareness is low and compliance rules may be unclear. The federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) requires most private health insurance plans that cover mental health and/or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) to make those benefits at least as generous as their medical and surgical benefits.

The Tennessee Department of Commerce & Insurance is responsible for enforcing MHPAEA requirements for Tennessee’s individual market and many employer-provided plans. (57) Enforcement generally stems from complaints filed by individual consumers. The number of complaints filed and actions taken by the TDCI, if any, are not publicly available. Some surveys and reports indicate Americans are largely unaware of MHPAEA requirements, have filed relatively few complaints nationally, and may continue to face barriers to accessing covered MH/SUD services. (58) (59)

Examples of Other Strategies

Assessing coverage practices, restrictions, and payments for addiction treatment may address some of the underlying drivers of the state’s provider and MAT capacity issues and comparatively low MAT utilization rates by Tennesseans covered by private insurance (discussed more above).

NGA recommends that states work to enforce MHPAEA, and SAMHSA has shared best practices for state implementation and enforcement. These include to:

- Ensure open communication with insurers on MHPAEA standards and requirements.

- Standardize materials so insurers know how the state will assess compliance.

- Create templates, workbooks, and other toolkits for the annual insurer filing process so that data are consistent and compliance is clear.

- Assess insurer practices and network adequacy to ensure MHPAEA compliance in fact as well as on paper.

- Collaborate across state agencies (e.g. health and behavioral health departments) and with consumer groups. (60)

Tennessee Private Health Insurance: Pending Legislation

Several pieces of legislation introduced in the Tennessee General Assembly in 2017 aim to raise awareness of MHPAEA requirements and ensure Tennessee’s enforcement of MHPAEA.

SB 839 / HB 1244 would make state insurance law consistent with the requirements in MHPAEA and require the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance to enforce MHPAEA. Senate status: Assigned to the Senate Commerce and Labor Subcommittee / House status: Expected to be considered on the first 2018 calendar of the House Insurance and Banking Subcommittee.

SB 835 / HB 871 would require a consumer and provider education campaign on MHPAEA. Senate status: Referred to the Senate Commerce and Labor Committee / House status: Assigned to the House Insurance and Banking Subcommittee.

SB 836 / HB 479 would require the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance to put in place MHPAEA enforcement mechanisms. Senate status: Referred to the Senate Commerce and Labor Committee / House status: Assigned to the House Insurance and Banking Subcommittee.

Treatment for Non-Violent Offenders

TDMHSAS works with the state’s judicial system to coordinate behavioral health care for individuals in the criminal justice system. In recent years, state policymakers have made efforts to expand access to treatment for these individuals primarily through recovery courts.

Examples of Existing Efforts

Recovery courts offer treatment services and alternative sentences for non-violent offenders who are veterans or have substance abuse and/or co-occurring mental illness. Recovery courts have been around since 1997, but TDMHSAS began oversight in 2012. The structure and specific available services vary by court. Participants receive various services such as residential or outpatient treatment, safe and sober housing, employment, child support and custody issues, and family counseling. (61)

TDMHSAS has increased the number of offenders served by recovery courts from about 1,400 in 2013 to over 4,800 in 2016. (11) Of Tennessee recovery court participants, 81% became employed or saw improvement in their job status and 63% maintained an independent living situation after completing the program. (62)

Examples of Other Strategies

Education about evidence-based opioid addiction treatment such as MAT, behavioral interventions, and other support services could help recovery court judges shape their programs. National best practices recommend that recovery courts provide access to MAT. (6) In some areas of Tennessee, pregnant women have reportedly been sent to a county jail to detox, which puts both the mother and fetus at risk. (63) MAT with methadone (and increasingly buprenorphine) is the standard of care for pregnant women with opioid dependence.

If MAT is not available or not wanted by the woman, detox should be medically supervised by an experienced physician. Some studies have found that sudden withdrawal is associated with high relapse rates, preterm labor, fetal distress, or fetal death. (64) Pregnant women, including those in recovery courts, should have access to evidence-based treatment managed by an obstetrician-gynecologist and an addiction medicine specialist.

Parting Words

Tennessee has implemented nearly all best practices for reducing the supply of prescription opioids and made some targeted investments in expanding treatment and recovery. Progress has been made, but the negative outcomes of the epidemic continue to mount. As state policymakers mull next steps, they may consider the current prevention and treatment environment in Tennessee and additional national best and emerging practices in these areas.

*This brief was updated on Dec. 12, 2017 to correct information about the ability of nonphysicians to prescribe buprenorphine in Tennessee.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Volkow, Nora D., et al. Medication-Assisted Therapies — Tackling the Opioid-Overdose Epidemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. [Online] May 29, 2014. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1402780

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Substance Abuse and Related Behavioral Health Problems. [Online] https://www.samhsa.gov/capt/sites/default/files/resources/aces-behavioral-health-problems.pdf

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Tennessee Increases Anti-Drug Coalitions To Prevent Substance Abuse. [Online] August 19, 2016. https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/news/2016/8/19/tennessee-increases-anti-drug-coalitions-to-prevent-substance-abuse.html

- —. Preventing Prescription Drug Abuse. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/substance-abuse-services/treatment—recovery/treatment—recovery/prescription-for-success/preventing-prescription-drug-abuse.html

- Wiltz, Teresa. States begin to use schools to fight opioid abuse. Washington Post. [Online] April 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/states-begin-to-use-schools-to-fight-opioid-abuse/2017/03/31/1474ec2c-14a2-11e7-ada0-1489b735b3a3_story.html?_hsenc=p2ANqtz-9O5vO4ZHGLxOlULb1074W0JA1GRnQ7fT2KNJmPXU8_qXJaMhg2qapDWC3wpvaTnmHY8OieGVw6PP

- National Governors Association. Finding Solutions to the Prescription Opioid and Heroin Crisis: A Road Map for States. [Online] 2016. https://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/2016/1607NGAOpioidRoadMap.pdf

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Integrating & Expanding Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Data: Lessons from Nine States. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Online] February 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pehriie_report-a.pdf

- Garza, Alex and Dyer, Sophia. EMS Data Can Help Stop the Opioid Epidemic. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. [Online] November 2016. http://www.jems.com/articles/print/volume-41/issue-11/features/ems-data-can-help-stop-the-opioid-epidemic.html

- Kinsman, Jeremiah, Elder, Jeffrey and Kanter, Joseph. Fighting the Opioid Crisis from the Front Lines. EMS World. [Online] 2016. http://www.emsworld.com/article/12252049/fighting-the-opioid-crisis-from-the-front-lines

- American Ambulance Association. Trinity EMS & FirstWatch Opioid Epidemic Project Awarded a 2016 AMBY for Best Use of Technology. [Online] 2016. https://ambulance.org/2016/11/05/2016-amby-best-use-technology-trinity-ems-firstwatch-opioid-epidemic-project/

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health & Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Prescription for Success Data Indicators. [Online] April 26, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/p-r-f/attachments/Rx_for_Success_Indicators_4.26.2017.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter 413. [Online] May 18, 2017. http://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/110/pub/pc0413.pdf

- Frakt, Austin. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Syringe Exchange Programs. AcademyHealth. [Online] September 2, 2016. https://www.academyhealth.org/node/2211

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). [Online] 2017. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). 2017 Needs Assessment Summary. [Online] May 25, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/p-r-f/attachments/2017_Needs_Assessment_Summary.pdf

- State of Tennessee. FY 2015-2016 State Budget. [Online] February 2015. http://www.tennessee.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2016BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf

- Texas Department of State Health Services. The Mental Health Workforce Shortage in Texas. [Online] September 2014. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwiA8qzXtu3SAhUI7CYKHTPQD7sQFgggMAE&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.dshs.texas.gov%2Flegislative%2F2014%2FAttachment1-HB1023-MH-Workforce-Report-HHSC.pdf&usg=AFQjCNE-QjrhsiI1P3E

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction: What Science Says. National Institutes of Health. [Online] February 2016. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/1921-understanding-drug-abuse-and-addiction-what-science-says.pdf

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Tennessee Opioid Treatment Clinics. [Online] 2017. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/sa/attachments/Tennessee_Opioid_Treatment_Clinics_Map%2C_locations.pdf

- Vestal, Christine. Few Doctors Are Willing, Able to Prescribe Powerful Anti-Addiction Drugs. The Pew Charitable Trusts. [Online] January 15, 2016. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/01/15/few-doctors-are-willing-able-to-prescribe-powerful-anti-addiction-drugs

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Buprenorphine in Tennessee. [Online] Feburary 18, 2016. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/p-r-f/attachments/Buprenorphine_Data_Brief_2.18.2016.pdf

- —. Emerging trends in prescribing buprenorphine: Tennessee 2015-2016. [Online] Feburary 15, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/p-r-f/attachments/Tennessee_BuprenorphineTrends_2015-2016.pdf

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services – 2010 State Profile – Tennessee. [Online] https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2010%20-%20NSSATS%20State%20Profiles/2010%20-%20NSSATS%20State%20Profiles/TN10.pdf

- —. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Centers: 2015. [Online] https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2015_National_Survey_of_Substance_Abuse_Treatment_Services.pdf

- —. Opioid Treatment Program Directory. [Online] 2017. http://dpt2.samhsa.gov/treatment/directory.aspx

- —. Qualify for Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Physician Assistants (PAs) Waiver. [Online] February 28, 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/qualify-nps-pas-waivers

- Vestal, Christine. Nurse Licensing Laws Block Treatment for Opioid Addiction. The Pew Charitable Trusts. [Online] April 21, 2017. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2017/04/21/nurse-licensing-laws-block-treatment-for-opioid-addiction

- State of Tennessee. TN Code § 53-11-311(c)(1). [Online] 2016. https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2016/title-53/chapter-11/part-3/section-53-11-311/

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction: What Science Says. National Institutes of Health. [Online] February 2016. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/1921-understanding-drug-abuse-and-addiction-what-science-says.pdf

- Baker, Nathan. TennCare’s lack of coverage for methadone treatment slowing opioid addiction response, advocates say. Johnson City Press. [Online] August 4, 2016. http://www.johnsoncitypress.com/Local/2016/08/03/TennCare-s-lack-of-coverage-for-methadone-treatment-slowing-opioid-addiction-response-advocates-say

- Li, Audrey M Bauer and Yinmei. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Maternal Substance Abuse in Tennessee: 1999-2011. Tennessee Department of Health. [Online] 2013. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/Neonatal_Abstinence_Syndrome_and_Maternal_Substance_Abuse_in_Tennessee_1999-2011.pdf

- Tennessee Department of Health. Constrolled Substance Monitoring Database 2017 Report to the 110th Tennessee General Assembly. Health Licensure & Regulation, Controlled Substance Monitoring Database Commitee. [Online] March 1, 2017. https://tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/2017_Comprehensive_CSMD_Annual_Report.pdf

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). State Inpatient Databases (SID). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). [Online] http://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/OpioidUseServlet

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multiple Causes of Death 1999-2015. National Center for Health Statistics, CDC WONDER Online Database. [Online] http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Fast Facts. [Online] April 7, 2017. http://tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/p-r-f/attachments/DPRF_Fast_Facts_4.7.2017_ke.pdf

- The Sycamore Institute. Analysis of funding for Community Alcohol and Drug Abuse Services / Community Substance Abuse Services in TDMHSAS. FY 2009-2010 – FY 2017-2018 Tennessee State Budgets and Tennessee Public Chapters 1108 (2010), 473 (2011), 1029 (2012), 453 (2013), 919 (2014), 427 (2015), and 758 (2016). [Online] 2017.

- Ebert, Joel. Tennessee needs millions more for opioid treatment, commissioner says. [Online] November 2016. http://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2016/11/21/commissioner-more-funding-for-treatment-needed-to-curb-opioid-epidemic/94242964/

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Tennessee to Receive $13.8 Million Aimed at Prescription Opioid Crisis. [Online] April 25, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/news/2017/4/25/tennessee-to-receive-13.8-million-aimed-at-prescription-opioid-crisis.html

- —. Prescription for Success: Statewide Strategeis to Prevent and Treat the Prescription Drug Abuse Epidemic in Tennessee. [Online] Summer 2014. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/sa/attachments/Prescription_For_Success_Full_Report.pdf

- Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. Performance Audit Report: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services and Statewide Planning and Policy Council. [Online] July 2016. http://www.comptroller.tn.gov/repository/SA/pa15073.pdf

- The Pew Charitable Trusts and The MacArthur Foundation. Substance Use Disorders and the Role of the States. [Online] March 2015. http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/03/substanceusedisordersandtheroleofthestates.pdf?la=en

- Tennessee Division of Health Care Finance and Administration. Chapter 1200-13-13.04. [Online] December 2016. http://publications.tnsosfiles.com/rules/1200/1200-13/1200-13-13.20161229.pdf

- Magellan Health Services. TennCare Preferred Drug List (PDL). [Online] April 2017. https://tenncare.magellanhealth.com/static/docs/Preferred_Drug_List_and_Drug_Criteria/TennCare_PDL.pdf

- —. Clinical Criteria, Step Therapy, and Quantity Limits for TennCare Preferred Drug List (PDL). [Online] June 1, 2017. https://tenncare.magellanhealth.com/static/docs/Preferred_Drug_List_and_Drug_Criteria/Criteria_PDL.pdf

- Tennessee Division of Health Care Finance and Administration. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Among TennCare Enrollees – 2015 Data. [Online] May 9, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/tenncare/attachments/TennCareNASData2015.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 221 (2017). [Online] April 28, 2017. http://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/110/pub/pc0221.pdf

- U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Best Practices for Addressing Prescription Opioid Overdoses, Misuse and Addiction. [Online] January 28, 2016. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib-02-02-16.pdf

- U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Letter: New Service Delivery Opportunities for Individuals with a Substance Use Disorder. [Online] July 27, 2015. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd15003.pdf

- Vestal, Christine. States Seek Medicaid Dollars for Addiction Treatment Beds. The Pew Charitable Trusts. [Online] April 2017. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2017/04/05/states-seek-medicaid-dollars-for-addiction-treatment-beds?utm_campaign=2017-04-05+Stateline+Daily&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Pew

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Behavioral Health: Options for Low-Income Adults to Receive Treatment in Selected States. [Online] June 2015. http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670894.pdf

- Wen, Hefei, Druss, Benjamin and Cummings, Janet. Effect of Medicaid Expansions on Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care among Low‐Income Adults with Behavioral Health Conditions. Health Services Research. [Online] December 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4693853/

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of Nonelderly 0-64. [Online] 2015. http://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/nonelderly-0-64/

- Blue Cross Blue Shield Association of America. America’s Opioid Epidemic and Its Effect on the Nation’s Commercially-Insured Population. [Online] June 29, 2017. https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/file-attachments/health-of-america-report/BCBS-HealthOfAmericaReport-Opioids.pdf

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Market Share and Enrollment of Largest Three Insurers- Large Group Market. [Online] 2014. http://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/market-share-and-enrollment-of-largest-three-insurers-large-group-market

- —. Market Share and Enrollment of Largest Three Insurers- Individual Market. [Online] 2015. http://www.kff.org/private-insurance/state-indicator/market-share-and-enrollment-of-largest-three-insurers-individual-market/

- —. Market Share and Enrollment of Largest Three Insurers- Small Group Market. [Online] 2014. http://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/market-share-and-enrollment-of-largest-three-insurers-small-group-market

- United States Government. Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. [Online] 2008. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Health-Insurance-Reform/HealthInsReformforConsume/downloads/MHPAEA.pdf

- Goodell, Sarah. Health Policy Brief: Enforcing Mental Health Parity. Health Affairs. [Online] November 9, 2015. http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_147.pdf

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). A Long Road Ahead: Achieving True Parity in Mental Health and Substance Use Care. [Online] 2015. https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead.pdf

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Approaches in Implementing the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act: Best Practices from States. [Online] August 8, 2016. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA16-4983/SMA16-4983.pdf

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Tennessee’s Recovery Courts. [Online] http://www.namitn.org/TDMHSAS%20Tennessee%20Recovery%20Court.pdf

- —. Recovery Courts Transforming Lives in Tennessee. [Online] May 2016. https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/news/2016/5/4/recovery-courts-transforming-lives-in-tennessee.html

- Wadhwani, Anita. For Small-Town Tennessee Judge, Opioid Crisis is Personal. The Tennessean. [Online] February 2017. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2017/02/05/small-town-tennessee-judge-opioid-crisis-personal/97527164/

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. Committee on Obstetric Practice, American Society of Addiction Medicine. [Online] August 2017. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Opioid-Use-and-Opioid-Use-Disorder-in-Pregnancy?IsMobileSet=false

Featured Image at top by Government of Alberta / CC BY-ND 2.0