See our 2018 Update on Indicators of Progress for more recent metrics and statistics. For a summary of how policymakers responded to Tennessee’s opioid epidemic during the 2018 legislative session, see our 2018 Update on New Policy Actions.

Key Takeaways

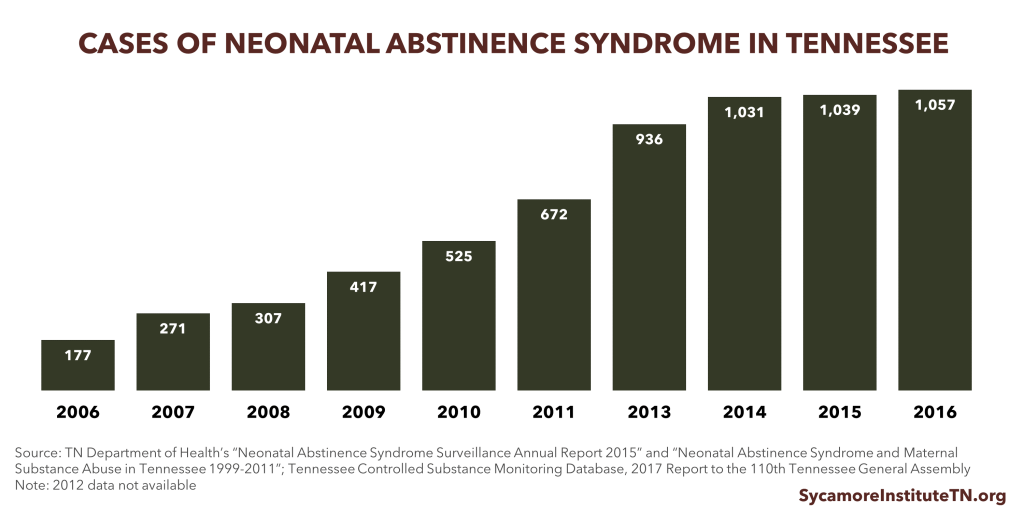

- Tennessee has largely focused on opioid prescription regulations and made a few targeted investments in substance abuse treatment.

- Tennessee has made significant progress in reducing opioid prescribing and dispensing. The number and potency of opioid prescriptions written in Tennessee has decreased.

- Even so, the number of opioid-related hospitalizations, deaths, and neonatal abstinence syndrome cases in Tennessee continues to rise.

Americans are the largest consumers of prescription opioids in the world. While these drugs can help individuals cope with chronic and acute pain, they are also increasingly misused. (1) Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. tripled between 1999 and 2014. By 2015, 63% of overdose deaths involved an opioid. (2)

The opioid epidemic has hit Tennessee especially hard. In 2012, our state had an average of 1.4 opioid prescriptions for every Tennessean — the 2nd highest rate in the U.S. (3) Prescription opioids have surpassed alcohol as the primary substance of abuse for treatment funded by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). The epidemic in Tennessee has resulted in higher opioid-related health care costs, more drug-related crimes, decreased work productivity, more children in state custody, and a 10-fold rise in babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome. (4) (5)

This report summarizes the policies Tennessee has implemented to address the epidemic and examines key indicators of progress. This is the first in a 3-part series that sets the stage for ongoing analyses of Tennessee’s opioid epidemic.

Bottom Line

Tennessee has made significant progress in reducing opioid prescribing and dispensing in recent years. That progress has not yet translated into a reduction in opioid-related hospitalizations, deaths, or neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

The state has partnered with stakeholders to implement an array of approaches to combat the problem in Tennessee. This robust policy response has largely focused on 2 areas:

- Prescribing Practices — Tennessee has expanded the use of its controlled substance monitoring database, issued prescribing guidelines, and regulated pain management clinics.

- Treatment Programs — The state has made targeted investments to expand substance abuse treatment options for individuals committing a criminal offense and provided additional funding for the substance abuse treatment safety net.

In the wake of these efforts, the number and potency of opioid prescriptions written in Tennessee has decreased. This may have resulted in fewer negative outcomes than would have otherwise occurred. Even so, the number of opioid-related hospitalizations, deaths, and NAS cases in Tennessee continues to rise. As the effectiveness of current policies becomes clearer and the opioid epidemic evolves, Tennessee has room to improve evidence-based treatment and prevention efforts to fight the epidemic.

Policy Milestones in Tennessee’s Opioid Epidemic Response

In 2012, Tennessee lawmakers began passing legislation to address prescription drug abuse. The new laws mostly focus on prescribing and dispensing practices, but they also address harm reduction and addiction treatment. Below, we highlight the major changes implemented and efforts undertaken over the last 5 years.

Tennessee Prescription for Success

In 2014, the state published a comprehensive overview of the problem, a status report on state policy efforts already underway, and a plan for moving forward. The Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS) published Prescription for Success: Statewide Strategies to Prevent and Treat the Prescription Drug Abuse Epidemic in Tennessee in collaboration with a number of state agencies and Governor Bill Haslam. The report established 7 goals for the state’s opioid response efforts: (4)

- Decrease the number of Tennesseans who abuse controlled substances.

- Decrease the number of Tennesseans who overdose on controlled substances.

- Decrease the amount of controlled substances dispensed in Tennessee.

- Increase access to drug disposal outlets in Tennessee.

- Increase access to and quality of early intervention, treatment, and recovery services.

- Expand collaborations and coordination among state agencies.

- Expand collaboration and coordination with other states.

Policies Related to Prescribing and Dispensing Practices

The Tennessee Prescription Safety Act of 2012 made comprehensive changes to providers’ prescribing and dispensing practices for prescription pain medicines. The law’s changes include:

- Health care providers and pharmacists are required to report all prescribing and dispensing of prescription opioids to the controlled substance monitoring database (CSMD) within 24 hours.

- They must also check the CSMD before prescribing or dispensing to a patient at the beginning of a new episode and at least every 6 months after that.(6)

The Tennessee Prescription Safety Act of 2016 made the 2012 law’s changes permanent, expanded the CSMD requirements to mental health hospitals, and allowed the U.S. Attorney’s office access to the CSMD. (7)

Tennessee has put a particular focus on “pill mills” by issuing targeted guidelines for pain management clinics and requiring registration and licensure. The state defines pain management clinics as private clinics that prescribe or dispense opioids or other controlled substances to the majority of their patients. Since 2012, all pain management clinics are required to register with the state and, under a 2016 law, undergo a licensure and inspection process. (8) (9)

In 2014, Tennessee finalized the Tennessee Chronic Pain Guidelines to provide clear instructions for opioid prescribers. Updated in 2016, these guidelines target prescriber practices at all stages of opioid therapy (i.e. prior to initiation, initiation, ongoing therapy). They also include information about proper prescription drug disposal, the use of naloxone, mental health assessment tools, treating pregnant women and women of childbearing age, and emergency department prescribing guidelines. (10)

Tennessee will soon issue guidelines for office-based use of opioid treatment medications. Office-based opioid clinics help integrate opioid abuse treatment into a patient’s regular medical care. In 2017, a law passed requiring treatment guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in nonresidential treatment settings. (11) A synthetic opioid, buprenorphine can help treat opioid addiction but can also be misused like other prescription opioids.

Harm Reduction and Good Samaritan Laws

Tennessee has enacted multiple laws to encourage people to seek medical attention if someone is experiencing a drug overdose and to mitigate the health risks associated with drug use. These laws include:

- Health providers can prescribe an opioid antagonist (i.e. naloxone) to a person at risk of experiencing an overdose or a family member, friend, or person who is likely to be in a position to assist someone at risk of experiencing an overdose.

- People who administer an opioid antagonist in good faith have civil immunity.

- Anyone who seeks medical assistance for a drug overdose for themselves or another person cannot be arrested, charged, or prosecuted unless there is gross negligence or willful misconduct.(12)

- Non-governmental agencies may operate needle and hypodermic syringe exchange programs if approved by the Tennessee Department of Health.(13)

Fetal Assault Law

The now-expired Tennessee fetal assault law was intended to prevent NAS but ultimately deterred pregnant women from seeking medical care. The law was enacted in 2014 to criminalize narcotics abuse while pregnant but was allowed to sunset on July 1, 2016. (14) Several doctors testified before the Tennessee House Criminal Justice Subcommittee that, in practice, the law deterred pregnant women from seeking medical care and endangered the lives of mothers and babies. (15)

Policies and Funding Initiatives Addressing Addiction Prevention and Treatment

The Safe Harbor Act of 2013 encourages and expands drug addiction treatment for pregnant women. It says:

- Pregnant women are considered priority users at publicly-funded treatment centers and cannot be turned away from treatment because they are pregnant.

- Obstetricians are required to encourage pregnant women who are using prescription drugs that may pose a risk to the fetus to enter drug addiction treatment.

- If a patient enters into drug dependence treatment and maintains compliance, the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services cannot petition for a newborn’s protection solely because the mother misused prescription drugs while pregnant.(16)

Over the last 5 years, the state budget has included a number of targeted funding increases related to substance abuse prevention and treatment. These have included:

Recurring funds:

- +$6.0 million beginning in FY 2017-2018 to expand safety net treatment and recovery services. (17)

- +$1.3 million beginning in FY 2016-2017 to expand recovery courts, which provide alternative sentencing and treatment services for non-violent offenders with substance abuse and/or mental health issues.(18)

Non-recurring funds:

- $1.9 million in FY 2013-2014 and FY 2015-2016 for adolescent residential alcohol and drug treatment. (19) (20)

- $0.5 million in FY 2013-2014, FY 2014-2015, and FY 2015-2016 for Lifeline Peer Programs that support local substance abuse recovery groups. (21) (22) (23)

- $0.5 million in FY 2015-2016 and $0.8 million in FY 2016-2017 for an opioid addiction treatment pilot within recovery courts. (20)(24)

- $0.5 million in FY 2013-2014 for residential adolescent substance abuse treatment. (19)

Other investments:

- Funding for 10 additional local anti-drug coalitions.

- Expanded drug-free recovery housing for adults. (25)

Indicators of Progress

Opioid prescribing and dispensing have declined in the wake of Tennessee’s efforts, but that progress has not yet translated to a reduction in the negative outcomes associated with opioid abuse.

Prescribing and Dispensing Patterns

Providers’ use of the state’s controlled substance monitoring database (CSMD) has increased in recent years, and the number and amount of prescriptions has declined.

- The number of controlled substance monitoring database registrants and use of the database have steadily increased. In 2016, there were 46,576 registrants. (26)

- The ratio of opioid prescriptions requested to the number actually dispensed has improved from 14:1 in 2010 to 3:1 in 2016. This suggests that practitioners are checking the database more frequently when treating patients and that fewer patients are attempting to “doctor shop.” (26)

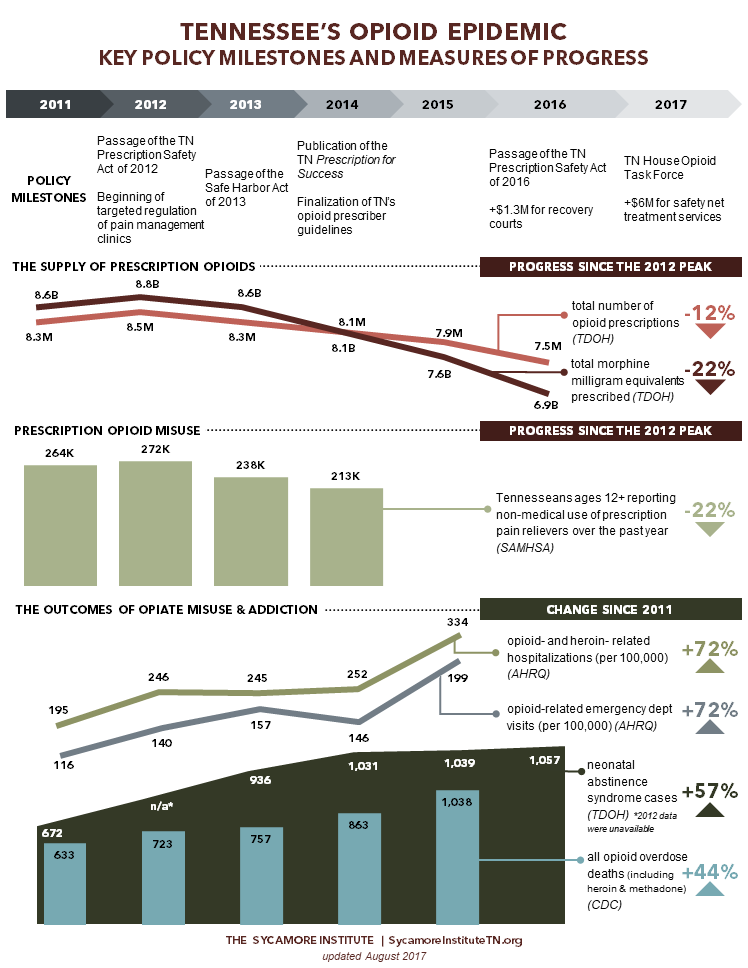

- Total morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) prescribed in Tennessee are down 9.5% since 2010 (Figure 1). (26) MMEs are a way to measure the strength of opioids being prescribed. Higher MMEs represent higher dosages.

- The total number of opioid prescriptions in Tennessee has fallen 7.8% from the peak in 2012 to 2015. (Figure 1). (30)

Figure 1

Prescription Opioid Misuse and Heroin Use

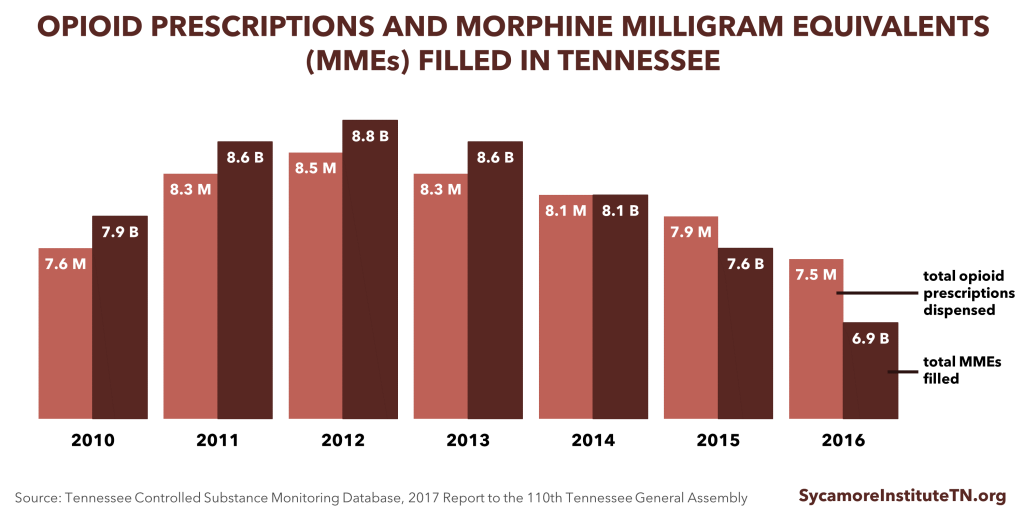

The number of Tennesseans reporting non-medical use of prescription pain relievers has fallen in recent years.

- An estimated 213,000 Tennesseans ages 12+ used prescription pain relievers for non-medical purposes in 2014, a 22% reduction since 2012 (Figure 2). (27)

- In 2015, an estimated 14,000 Tennesseans ages 12+ used heroin in the past year. (31)

- The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) tracks trends in drug use. Until their most recent survey, SAMHSA did not report state-specific estimates of past year heroin use.

Figure 2

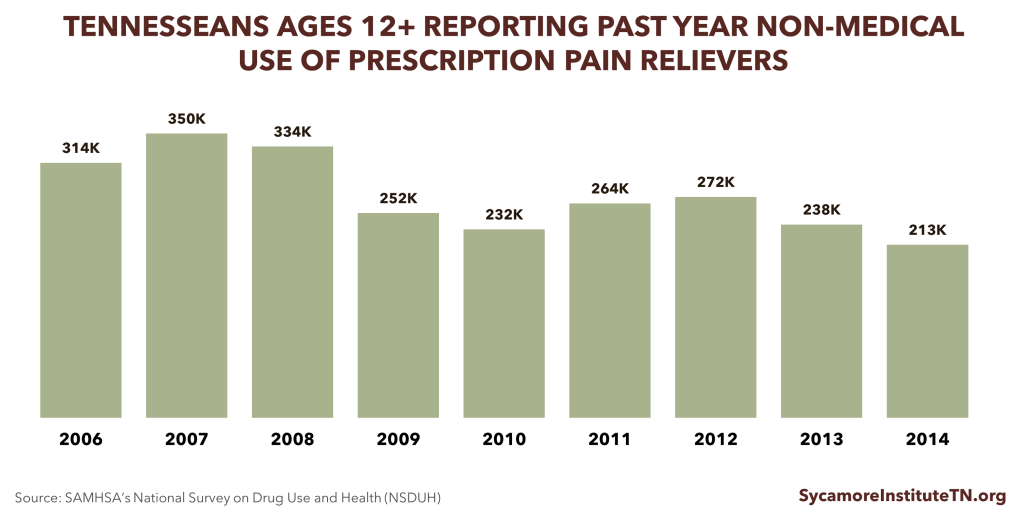

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

The number of babies born with withdrawal symptoms that result from their mothers’ use of opioids has increased rapidly in recent years. These symptoms are known as neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

- From 2005 to 2016, the number of NAS children born in Tennessee annually increased from 174 to 1,057, a 6-fold increase (Figure 3). (29) (26)

- Based on comparisons of data from the Tennessee Department of Health and TennCare, TennCare is the primary payer for NAS cases in Tennessee. (29)(32)

- The rise in NAS cases has increased the state’s health care expenditures. TennCare spends almost 10 times more for babies with NAS in the first year than for normal birth weight infants $44,000 versus $4,800. (32)

- NAS cases include infants born to mothers on medication-assisted treatment for opioid abuse (i.e. Methadone, Buprenorphine). (33)

Figure 3

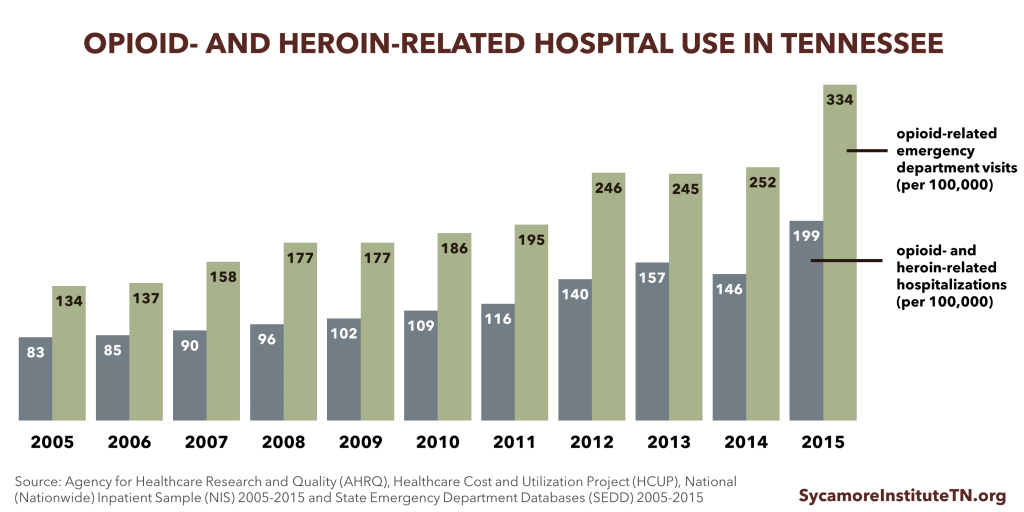

Opioid and Heroin Overdose Hospitalizations

Rates of opioid- and heroin-related hospital visits and stays have steadily increased over the last decade.

- The rate of opioid- and heroin-related inpatient stays increased 88% between 2005 and 2014 (Figure 4). (34)

- The rate of opioid-related emergency department (ED) visits has steadily increased over the last decade, but experienced a 7% decrease between 2013 and 2014 (Figure 4). (35)

- Nationally, Medicaid is the primary payer for opioid-related hospitalizations. In 2012, the national Medicaid costs for opioid-related hospitalizations reached almost $15 billion. (36)

Figure 4

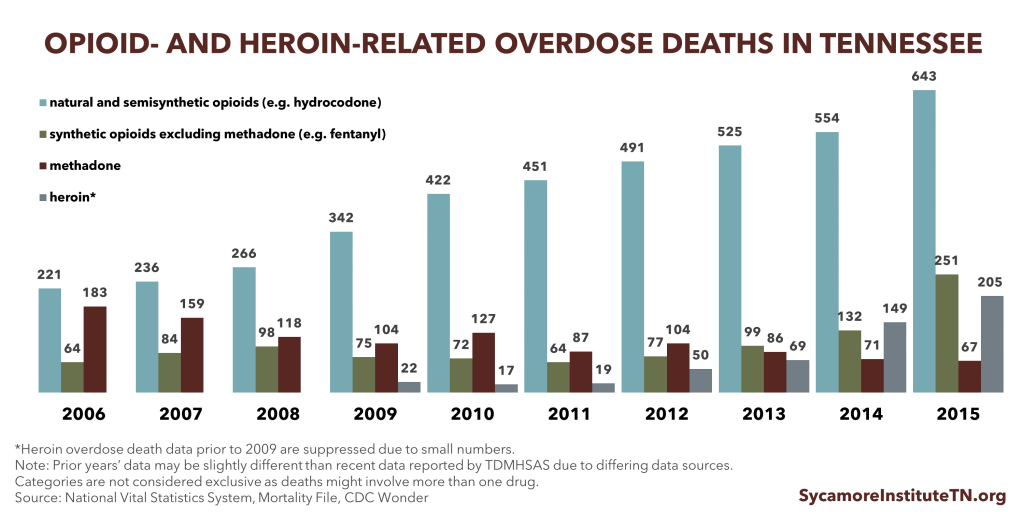

Opiate Overdose Deaths

The number of opioid prescriptions and their MMEs have decreased, but the number of overdose deaths continues to rise (Figure 5). (37) Reporting of opioid overdose death relies on autopsy report codes on death certificates. The number of opioid overdose deaths is likely underestimated due to autopsies not being performed or opioids not being listed on death certificates because of stigma or the presence of other diseases. (38) (39) (40)

Another emerging trend is the increasing incidence of overdose deaths from the use of heroin and synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Although data show that fewer individuals are misusing prescription opioids and state-specific data on heroin use are not publically available, this trend in overdose deaths suggests that individuals are switching from prescription opioids to heroin and fentanyl. The switch from common prescription opioids to other opioids is evidence that Tennessee has made it more difficult to obtain prescription drugs, but the demand for opiates remains.

- Heroin: Reasons for the switch from opioids to heroin include the increasing difficulty of obtaining prescription medicines, the greater ease of obtaining heroin, and the lower cost of heroin. The risk of heroin overdose is very high because users have no knowledge of or control over the purity of the drug, and it may be contaminated with other drugs. Heroin use also presents other health risks because it is typically injected intravenously and is associated with the transmission of diseases like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C. (1)

- Synthetic Opioids: Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is 50 times stronger than heroin — posing a greater risk for overdose. Although it is a prescription drug, it is increasingly sold illegally. It is often mixed with heroin or sold in pill form as another drug (e.g., OxyContin®, Xanax®, Norco®). This means that people often do not know they are taking fentanyl. Because it is extremely potent, the risk of overdose is much higher compared to other opioids. (41)

Figure 5

Parting Words

Tennessee has been a national leader in implementing evidence-based policies to address the opioid epidemic, which have helped reduce the supply of opioid prescriptions. The negative outcomes of opioid addiction may have been worse without these efforts. However, opioid-related abuse, hospitalizations, and overdoses continue to rise. While Tennessee has done well in nearly all facets of addressing the opioid supply, the evidence suggests that demand for opiates remains.

In Part 2 and Part 3 of this introductory series, we will discuss evidence-based prevention and treatment for opioid misuse and addiction and the current prevention and treatment environment in Tennessee.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Volkow, Nora D. America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse. Presentation to Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control. [Online] May 2014. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse.

- Rudd, Rose A, et al. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). [Online] December 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC Vital Signs: Opioid Painkiller Prescribing. [Online] July 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2014-07-vitalsigns.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. Prescription for Success: Statewide Strategies to Prevent and Treat the Prescription Drug Abuse Epidemic. [Online] 2014. https://tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/sa/attachments/Prescription_For_Success_Full_Report.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Health. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) Frequently Asked Questions. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/NAS_FAQ.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 880 (2012). [Online] April 27, 2012. http://www.tn.gov/sos/acts/107/pub/pc0880.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 1002 (2016). [Online] April 27, 2016. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/pc1002.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Health Division of Pain Management Clinics. Chapter 1200-34-01 Pain Management Clinics. [Online] March 2012. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/1200-34-01.20120326.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 1033 (2016). [Online] April 28, 2016. http://tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/pc1033.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Health. Tennessee Chronic Pain Guidelines: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Outpatient Management of Chronic Non-Malignant Pain, 2nd Edition. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/ChronicPainGuidelines.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 112 (2017). [Online] April 7, 2017. http://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/110/pub/pc0112.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 623 (2014). [Online] April 4, 2014. http://www.tn.gov/sos/acts/108/pub/pc0623.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 413 (2017). [Online] May 18, 2017. http://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/110/pub/pc0413.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 820 (2014). [Online] April 28, 2014. http://www.tn.gov/sos/acts/108/pub/pc0820.pdf.

- Gonzalez, Tony. Tennessee Fetal Assault Bill Fails, Allowing It To Be Struck From State Law. Nashville Public Radio. [Online] March 22, 2016. http://nashvillepublicradio.org/post/tennessee-fetal-assault-bill-fails-allowing-it-be-struck-state-law#stream/0.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 398 (2013). [Online] April 17, 2013. http://www.tn.gov/sos/acts/108/pub/pc0398.pdf.

- —. FY 2017-2018 State Budget. [Online] 2017. https://tn.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2018BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- —. FY 2016-2017 State Budget. [Online] 2016. http://www.tennessee.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2017BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 453 (2013). [Online] May 16, 2013. http://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/108/pub/pc0453.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 427 (2015). [Online] May 18, 2015. http://share.tn.gov/sos/acts/109/pub/pc0427.pdf.

- —. FY 2013-2014 State Budget. [Online] 2013. http://www.tennessee.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2014BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- —. FY 2014-2015 State Budget. [Online] 2014. http://www.tennessee.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2015BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- —. FY 2015-2016 State Budget. [Online] 2015. http://www.tennessee.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2016BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- State of Tennessee . Public Chapter No. 758 (2016). [Online] April 21, 2016. http://share.tn.gov/sos/acts/109/pub/pc0758.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Prescription for Success Achievements. [Online] July 1, 2016. https://tn.gov/assets/entities/behavioral-health/sa/attachments/Prescription_for_Success_Achievements_7-1-2016.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Health. Controlled Substance Monitoring Database 2017 Report to the 110th Tennessee General Assembly. Health Licensure & Regulation, Controlled Substance Monitoring Database Committee. [Online] March 1, 2017. https://tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/2017_Comprehensive_CSMD_Annual_Report.pdf.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Interactive NSDUH State Estimates. [Online] http://pdas.samhsa.gov/saes/state.

- Miller, A M and Warren, M D. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Surveillance Annual Report 2016. Tennessee Department of Health, Division of Family Health and Wellness. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/NAS_Annual_report_2015_FINAL.pdf.

- Bauer, Audrey M and Li, Yinmei. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Maternal Substance Abuse in Tennessee: 1999-2011. Tennessee Department of Health. [Online] 2013. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/Neonatal_Abstinence_Syndrome_and_Maternal_Substance_Abuse_in_Tennessee_1999-2011.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Health. Controlled Substance Monitoring Database, 2016 Report to the 109th Tennessee General Assembly. [Online] February 2016. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/health/attachments/CSMD_AnnualReport_2016.pdf.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2014-2015 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. [Online] https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHsaeTotals2015A/NSDUHsaeTotals2015.pdf.

- Tennessee Division of Health Care Finance and Administration. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Among TennCare Enrollees – 2015 Data. [Online] May 9, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/tenncare/attachments/TennCareNASData2015.pdf.

- Logan, Beth A, Brown, Mark S and Hayes, Marie J. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Treatment and Pediatric Outcomes. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 56(1) : 186-192. [Online] 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3589586/pdf/nihms431948.pdf.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). State Inpatient Databases (SID) . Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). [Online] https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/OpioidUseServlet.

- Agency for Healthcare Researcj and Quality (AHRQ). State Emergency Department Databases (SEDD). Helathcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). [Online] https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/OpioidUseServlet.

- Ronan, Matthew V and Herzig, Shoshana J. Hospitalizations Related to Opioid Abuse/Dependence and Associated Serious Infections Increased Sharply, 2002-12. Health Affairs, 35(5), 832-837. [Online] 2016. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/5/832.abstract.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2015. National Center for Health Statistics, CDC WONDER Online Database. [Online] http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html.

- Hall, Victoria, et al. Deaths Associated with Opioid Use and Possible Infectious Disease Etiologies Among Persons in. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Online] https://www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/cdc-24-7/eis-conference/pdf/Infectious-disease-complicates-opioid-overdose-deaths.pdf.

- National City-County Task Force on the Opioid Epidemic. Summary of the Task Force’s Inaugural Convening. National Association of Counties. [Online] April 2016. http://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/Summary%20of%20April%207%20National%20City-County%20Task%20Force%20on%20the%20Opioid%20Epidemic.pdf.

- Associated Press. Overdose Deaths Stressing Limits of Medical Examiner, Coroner Offices. [Online] June 2016. https://www.statnews.com/2016/06/23/overdose-deaths-medical-examiner-coroner/.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influx of Fentanyl-laced Counterfeit Pills and Toxic Fentanyl-related Compounds Further Increases Risk of Fentanyl-related Overdose and Fatalities. [Online] 2016. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00395.asp.