Insurers have attributed recent premium increases in Tennessee’s healthcare.gov Marketplace to enrollees being sicker and more costly than expected. What can be done to alleviate rising costs while maintaining access to insurance for the sickest? Lately, two options have drawn increased attention:

- Reinsurance to insulate insurers from the high costs associated with high-risk individuals, and

- Stand-alone high-risk pools to separate high-risk individuals from the rest of the market.

This policy brief explains these terms and how they relate to emerging federal funding opportunities for Tennessee.

Bottom Line

Tennessee policymakers may want to consider reinsurance and/or high-risk pools in response to proposed federal policy changes and emerging federal funding opportunities. Both mechanisms may improve the affordability of health insurance premiums in the Marketplace, but each has benefits and trade-offs.

Status of Tennessee’s Marketplace

In 2017, premiums in Tennessee’s healthcare.gov Marketplace grew faster than the national average, insurer participation was down, and enrollment declined. Nevertheless, over 234,000 Tennesseans remain enrolled in Marketplace health insurance for 2017. Some people believe these trends mark the destabilization of the state’s Marketplace. Others view them as indicators of a steep but temporary market correction. Differing viewpoints aside, rising insurance costs create a barrier for some individuals to access health insurance.

Potential Federal Funding

Federal funding may be available to states — now under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and in the future under other Congressional proposals — to create new state-run reinsurance programs and/or high-risk pools aimed at stabilizing the individual health insurance market and making insurance more affordable.

Benefits of Reinsurance and High-Risk Pools

- Both mitigate the impact of high-risk enrollees on insurers, which tends to make insurers’ risk more predictable and premiums more stable. For example, when Alaska implemented a reinsurance program for its Marketplace in 2016, an expected 47% premium increase was limited to 7%.

- Both spread the costs of high-risk enrollees across a larger population than insurance alone because they are often funded with taxpayer dollars or insurer fees.

Trade-offs of Reinsurance and High-Risk Pools

- High-risk pools are costly for taxpayers and enrollees. Consequently, they may only meet some of the need. States’ pre-ACA experiences confirm this. (See Tennessee’s High-Risk Pool Experience for a review of Tennessee’s program, AccessTN.)

- Reinsurance may remove insurers’ incentives to manage high-risk enrollees’ costs and care by insulating plans from very high costs.

Why Does this Matter?

Stable and affordable insurance premiums are generally understood to be a result of broad and stable risk pools. These mechanisms may help increase affordability and encourage insurer participation in the Marketplace by helping to make insurers’ risk more predictable and to attract lower-risk individuals to purchase coverage.

What Are the Issues?

The discussion about reinsurance and high-risk pools revolves around four primary issues.

1) Predictable Costs for Insurers

Broad and predictable risk pools help keep costs predictable for insurers. Most actuaries agree that health insurance works best when the risk in any given risk pool is broad and stable. (1) This helps keep costs predictable for insurers, which keeps insurance premiums more affordable and annual rate increases more manageable. These qualities make insurance more attractive for individuals with low and moderate risk who arguably need insurance the least.

In many ways, it is cyclical: low-risk individuals are more likely to enroll when premiums are low, and the enrollment of low-risk individuals is an important driver of keeping premiums low. So long as high-risk individuals are in the same pool as low-risk ones, however, these premiums are still likely to be higher than low-risk individuals may otherwise be charged or willing to pay. (See Health Insurance Markets 101 for more information on some of the key concepts that impact health insurance access and affordability.)

2) Incentives for Enrollment

A mix of subsidies and penalties incentivize more individuals to buy insurance, which helps create a broad risk pool. Both the ACA and the proposed American Health Care Act (AHCA) include mechanisms that try to increase the affordability and attractiveness of insurance for all individuals – such as subsidies and tax credits.

The ACA and the AHCA also both try to make health insurance enrollment more attractive, for low- and moderate-risk individuals in particular, by increasing the costs of not enrolling. The ACA includes a flat monetary penalty for failure to enroll in health insurance (i.e. the individual mandate). The AHCA would require that insurers charge individuals 30% higher premiums for 1 year for new enrollees who have gone without coverage for more than 63 days during the previous 12 months. (2)

3) Dangers of Concentrated Risk

Failure to attract diverse levels of risk into the pool leads to market instability. Problems can arise if premium costs make the penalty more attractive than enrollment for lower-risk individuals. These individuals may choose not to enroll, leaving a costlier pool that requires higher premiums. As the trend continues, coverage can become prohibitively expensive for everyone. This is often called market destabilization and, in extreme cases, a death spiral.

Can the Marketplaces Death Spiral?

Health insurance Marketplaces across the country have recently experienced insurer exits and double-digit premium increases. Because the ACA’s subsidy amounts are tied to premium costs, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office argues that enrollees are insulated from the impact of premium increases.

As a result, the Marketplaces would not enter a true “death spiral” so long as the government remained willing to fund the growing expense of the subsidies as currently structured. (14)

4) Keeping Insurers in the Marketplace

Insurers need to see a path to a predictable risk pool, or they won’t participate. Insurers’ bottom lines depend on whether their premiums cover the costs of their enrollees. Adequate pricing requires accurate forecasting. Tennessee’s Marketplace insurers have struggled with offering premiums that were too low to cover the actual costs of their enrollees.

Insurers anticipated and were willing to accept some initial uncertainty associated with Marketplace enrollment at least partially because the ACA included temporary mechanisms (reinsurance and risk corridors) intended to address this initial uncertainty. The mechanisms were aimed at providing a safety net for insurers while Marketplace enrollment ramped up and the needs and costs of Marketplace enrollees became more predictable.

Unexpected developments, however, introduced new uncertainty into the Tennessee Marketplace. For example, the federal government was unable to fully carryout one of the temporary mechanisms (risk corridors), which hurt many insurers and contributed to the closure of one of Tennessee’s Marketplace insurers. Now, the President and Congress are considering both regulatory and statutory changes that make the future of the individual health insurance market less clear. Insurers are only willing to accept so much unpredictability before they decline to participate altogether.

Tennessee’s Health Insurance Marketplace

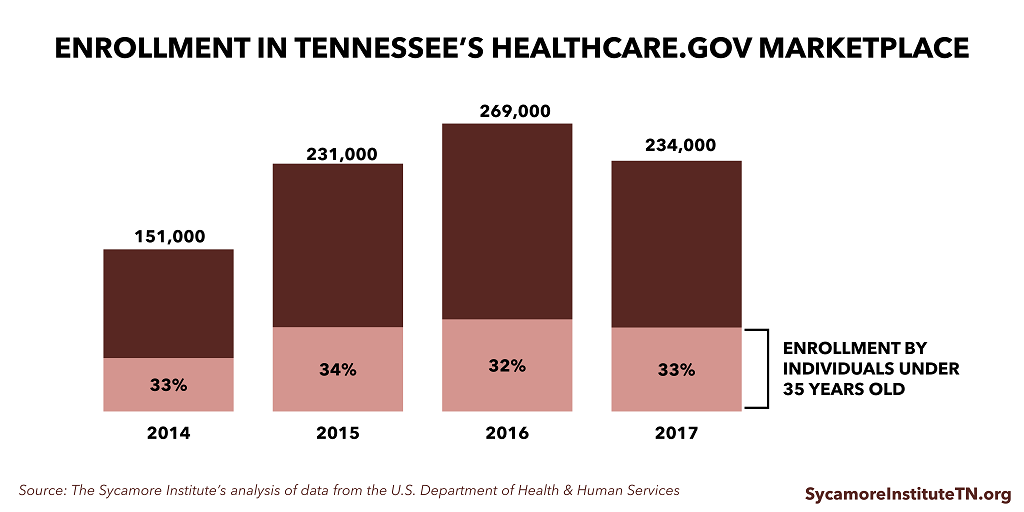

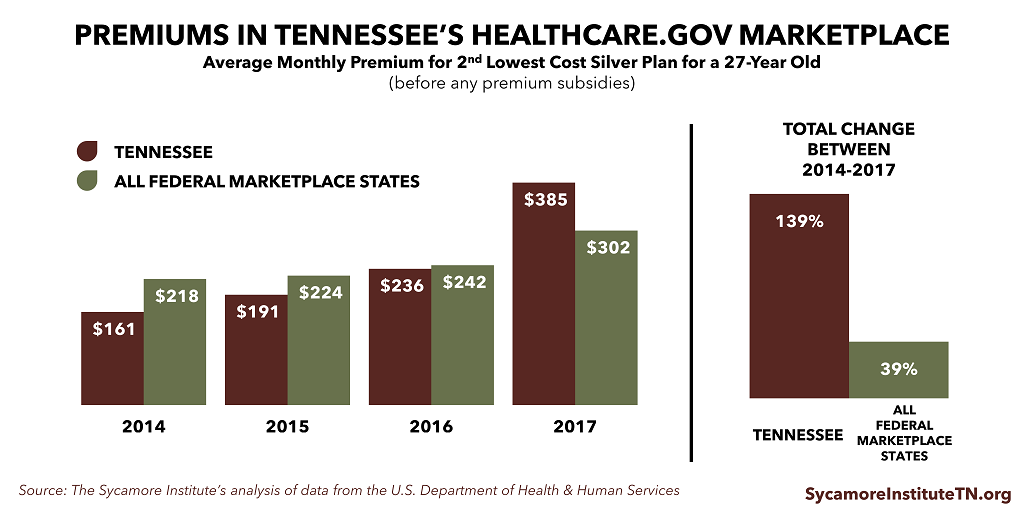

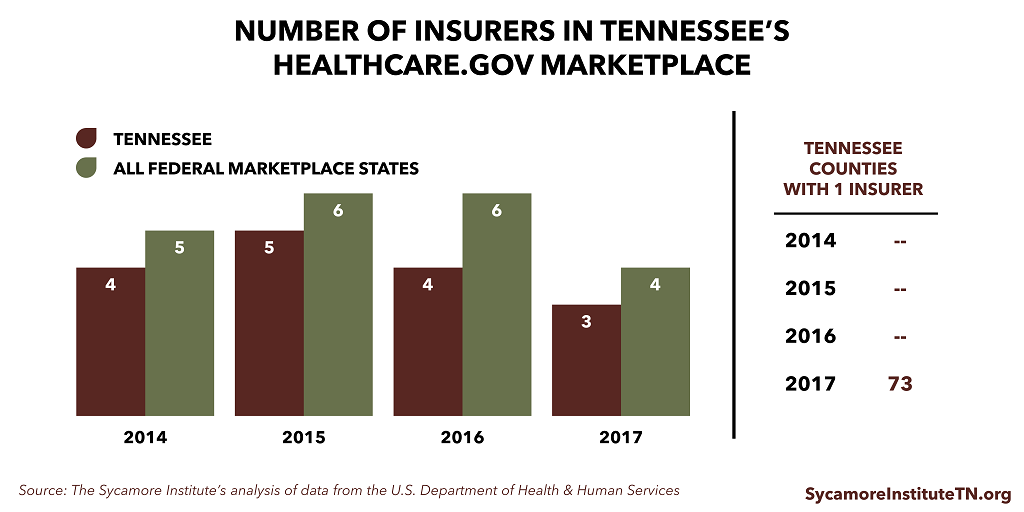

The images below illustrate trends in Tennessee’s health insurance Marketplace.

Enrollment by individuals under 35 years did not change as a percentage of total enrollment over the time period. Total enrollment grew for 2014, 2015, and 2016 but receded for 2017.

Premiums in Tennessee’s Marketplace were lower than average federal Marketplace premiums in 2014, 2015, and 2016 but higher in 2017.

Insurer participation in Tennessee’s Marketplace has been lower than average for all federal Marketplace states. In 2017, Tennessee went from having 0 counties with only 1 insurer to 73 counties with only one insurer.

Tennessee’s own Insurance Commissioner believes that the state’s individual health insurance market has become destabilized. (5) She and many others view the recent premium increases and insurer exits as indicators that the state’s Marketplace is on the verge of collapse. Although insurers have until June 21st to decide about 2018 Marketplace participation (3), Humana has already announced it will no longer participate in Marketplaces. This would leave 2 insurers in Tennessee’s Marketplace, 71 counties with only 1 insurer, and 16 counties with no insurers. (4)

Tools to Stabilize the Marketplace and Encourage Insurer Participation

Recently, both reinsurance and high-risk pools have been discussed nationally as options for stabilizing the individual health insurance market and encouraging insurer participation in both the short- and long-term.

What is Reinsurance?

Reinsurance is essentially insurance for insurers. Reinsurance programs reimburse insurers for particularly high-cost cases. Reinsurance payments are often triggered by a predetermined cost threshold. They are often paired with other mechanisms aimed at mitigating and spreading insurers’ risks – like risk adjustment and risk corridors. Risk adjustment programs transfer funds between plans with relatively lower-risk enrollees and those with relatively higher-risk enrollees, and risk corridor programs partially offset large losses and require sharing of large profits.

The ACA included a temporary reinsurance program for 2014-2016 intended to help stabilize premiums in the face of unpredictable costs for new enrollees with potentially poor health status. In 2014, the program reimbursed plans for 80% of any enrollee costs above $45,000. The program was funded by a flat fee paid by all insurers for each of their enrollees across both the individual and group markets. (6) The ACA also included a permanent risk adjustment program and a temporary risk corridor program that was never fully implemented.

What are High-Risk Pools?

High-risk pools are separate health insurance plans specifically for high-risk individuals. Prior to the implementation of the ACA’s reforms in 2014, states and the federal government used these pools to cover people considered “uninsurable.” Recently, concepts of virtual or invisible high-risk pools, high-risk pool reimbursement programs, and condition-based high-risk pool reimbursement programs have been discussed. Although called “high-risk pools,” conceptually, these work more like reinsurance programs because they would all allow high-risk individuals to enroll in individual market plans, and plans would be reimbursed for any high costs associated with specific individuals or individuals with specific diagnoses. (7) (8)

Prior to the passage of the ACA, Tennessee and 34 other states offered high-risk pools. Although eligibility criteria varied, they were often open to individuals who had been denied coverage in the individual health insurance market due to a pre-existing health condition and who had gone without insurance for 6-12 months. These pools were funded by a varying mix of enrollee premiums, insurer fees, state taxpayer dollars, and federal grants. These high-risk pools capped premiums – usually at twice the individual market rate for a typical enrollee. Some – but not all – provided premium assistance for low-income enrollees. The Kaiser Family Foundation recently estimated that state high-risk pools covered over 200,000 people nationwide at their peak. (See Tennessee’s High-Risk Pool Experience for a summary of Tennessee’s high-risk pool AccessTN.) (9)

The ACA established a national high-risk pool known as the Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Program (PCIP). The purpose was to offer uninsurable individuals a coverage option during the time between the law’s passage in 2010 and the implementation of the law’s reforms in 2014. (9)

Benefits

Both approaches mitigate the impact of high-risk enrollees on insurers, which help make insurers’ risk more predictable and premiums more stable. Using different mechanisms, both reinsurance and high-risk pools insulate insurers from the very high costs associated with sicker, higher-risk individuals. This helps keep insurers’ costs lower and more predictable. This may translate to more affordable and stable premiums that are more attractive to low- to moderate-risk individuals seeking insurance and greater insurer participation.

The Medicare Part D prescription drug program has a permanent reinsurance program for the private plans that administer the program’s benefits to Medicare enrollees. The program’s risk-sharing approach (which includes reinsurance, risk corridors, and risk adjustment) has proven successful at ensuring insurer participation and competition and plan choice for beneficiaries. (10)

Both mechanisms spread the costs of high-risk enrollees across a larger population than insurance alone because they are often funded with taxpayer dollars or insurer fees. In the absence of these mechanisms, healthier individuals in a health plan essentially subsidize the costs of sicker individuals in the same plan or risk pool. Depending on how they are funded, reinsurance and high-risk pools spread high costs across a broader swath of people (all taxpayers in the case of direct government subsidy or all insured individuals in the case of an insurer assessment). (11)

Reinsurance programs offer access and options to high-risk individuals. Reinsurance programs (and similar mechanisms like “invisible” high-risk pools) have the additional benefit of keeping high-risk individuals in the same pool with access to the same options as others in the individual health insurance market. (11)

Challenges and Unintended Consequences

Both high-risk pools and reinsurance may have challenges and unintended consequences. For example, the structure and requirements of high-risk pools prior to the implementation of the ACA created challenges to meeting the needs of high-risk, uninsurable individuals.

While premiums for high-risk pool enrollment were often capped, they remained unaffordable for many. Funding for premium assistance was limited or unavailable in most states due to finite funding sources and other demands on the pools’ funding. By definition, high-risk pools concentrate the most costly patients in a single pool. Because premiums for high-risk pools were capped, other methods were required to keep costs in check. As a result, high-risk pools often required high deductibles and cost-sharing and included lifetime and annual limits.

High-risk pools also included limitations on eligibility and benefits that affected affordability and access to needed care for enrollees. For example, most high-risk pools required that individuals be uninsured for 6-12 months before enrolling and restricted coverage for any pre-existing conditions for certain periods – sometimes up to the first year of enrollment.

High-risk pools are costly for both taxpayers and enrollees, and consequently they can only meet some of the need. Even with these cost management practices in place, high-risk pools paid far more in claims for enrollees than they collected in premiums. In 2011, claims exceeded premiums by about $5,510 per high-risk pool enrollee nationwide. These differences were covered by insurer assessments, state taxpayer dollars, and, at times, federal grants. The limited nature of these funding sources – including the pressure on state revenues during economic downturns – meant that premium assistance was often limited and high-risk pool enrollment was often capped or closed. (9) (12)

Additionally, because high-risk pools are separate from the individual market, high risk individuals could be subject to different standards, requirements, and consequences associated with the policies and management of the pool. Examples might include provider payment rates and care management activities.

Reinsurance may remove insurers’ incentives to effectively manage high-risk enrollees’ costs and care by insulating plans from very high costs. This challenge is mitigated, however, by requiring insurers to continue to share in some portion of the high costs (e.g. only reimburse insurers for 80% of the costs above the threshold). (10) (11)

Emerging Funding Opportunities for States

Reinsurance and high-risk pools have recently received greater attention as potential ways to improve affordability and choice in the individual health insurance market both in the short- and long-term. Tennessee policymakers should consider the trade-offs associated with these mechanisms when evaluating future federal funding opportunities.

The ACA’s Section 1332 State Innovation Waivers – On March 13, 2017, U.S. Health & Human Services Secretary Tom Price sent a letter to state governors suggesting that federal funding may currently be available under the ACA’s Section 1332 State Innovation Waivers. These waivers allow federal funding to support state coverage innovations so long as they are budget-neutral and would not negatively affect coverage rates. The letter suggests that such a waiver may provide an opportunity for states to receive existing federal funding to implement a high-risk pool or reinsurance program to counter the recent signs of destabilization in the Marketplaces. (13)

The Alaska Reinsurance Program

Secretary Price’s letter points to recent efforts in Alaska to combat large Marketplace premium increases. In 2017, Alaska’s one remaining Marketplace insurer had proposed a 47% premium increase for 2017. In response, the legislature provided $55 million in state funding for an individual market reinsurance program. Once passed, final Marketplace premium increases were reduced to 7%.

Alaska has applied for a Section 1332 waiver, arguing that, by bringing down premiums, the reinsurance program saved the federal government $52 million through reduced premium subsidy costs and increased enrollment. If approved, those federal savings would be passed to the state for the reinsurance program. (24) (13)

The AHCA’s Patient and State Stability Fund – Looking forward, the AHCA proposes a Patient and State Stability Fund that would allot funds to states beginning in 2018 to help high-risk individuals access coverage (among other purposes). $15 billion would be available in each of 2018 and 2019. In 2020-2026, $10 billion per year would be available along with a required state match of 10%-50%. If a state chooses not to apply for funding, the federal government would use the funds to administer a reinsurance program in that state. CBO estimated that the implementation of a reinsurance program through the Stability Fund would, in the context of the AHCA’s other reforms, lower individual market premiums and encourage insurer participation. (14)

Parting Words

We all want better health and well-being for Tennesseans. While many factors influence health, insurance can open the door to services that help us get and stay healthy. Rising premium costs and declining insurer participation in Tennessee’s Marketplace represent a barrier to accessing health insurance. State policymakers should think carefully about ways to maximize opportunities for all Tennesseans to access the health coverage that meets their needs.

Tennessee’s High-Risk Pool Experience

Tennessee created its own high-risk pool, AccessTN, in 2006. For a history of that program, read Tennessee’s High-Risk Pool Experience.

References

Click to Open/Close

1. American Academy of Actuaries. Critical Issues in Health Reform: Risk Pooling. [Online] July 2009. http://www.actuary.org/pdf/health/pool_july09.pdf.

2. U.S. House of Representatives. American Health Care Act. [Online] 2017. https://housegop.leadpages.co/healthcare/.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Key Dates for Calendar Year 2017: QHP Certification in the Federally-Facilitated Marketplaces. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Online] February 2017. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/Revised-Key-Dates-for-Calendar-Year-2017-2-17-17.pdf.

4. Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance. Tennessee’s Health Insurance Marketplace and the ACA. Presentation to Tennessee Senate Commerce and Labor Committee. February 21, 2017. http://tnga.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=399&clip_id=12904.

5. Fletcher, Holly. Tennessee insurance commissioner: Obamacare exchange ‘very near collapse’. The Tennessean. [Online] August 23, 2016. http://www.tennessean.com/story/money/industries/health-care/2016/08/23/insurers-get-approval-for-2017-obamacare-rates/89196762/.

6. The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight. The Transitional Reinsurance Program. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Online] https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Premium-Stabilization-Programs/The-Transitional-Reinsurance-Program/Reinsurance-Contributions.html.

7. Allumbaugh, Joel, Bragdon, Tarren and Archambault, Josh. Invisible High-Risk Pools: HowCongress Can Lower Premiums And Deal With Pre-Existing Conditions. Health Affairs Blog. [Online] March 2, 2017. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/03/02/invisible-high-risk-pools-how-congress-can-lower-premiums-and-deal-with-pre-existing-conditions/.

8.American Academy of Actuaries. Using High-Risk Pools to Cover High-Risk Enrollees. [Online] February 2017. http://www.actuary.org/files/publications/HighRiskPools_021017.pdf.

9. Pollitz, Karen. High-Risk Pools for Uninsurable Individuals. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] February 22, 2017. http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/high-risk-pools-for-uninsurable-individuals/.

10. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). Sharing Risk in Medicare Part D.Report to Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. [Online] June 2015. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-6-sharing-risk-in-medicare-part-d-june-2015-report-.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

11. Haislmaier, Edmund. State Health Care Reform: The Benefits and Limits of “Reinsurance”. The Heritage Foundation . [Online] July 26, 2007. http://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/state-health-care-reform-the-benefits-and-limits-reinsurance.

12. Hall, Jean. Why a National High-Risk Pool is not a Workable Alternative to the Marketplace. The Commonwealth Fund. [Online] December 11, 2014. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2014/dec/national-high-risk-insurance-pool.

13. Price, Tom. Letter to Governors re: Section 1332 Waivers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . [Online] March 13, 2017. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/State-Innovation-Waivers/Downloads/March-13-2017-letter_508.pdf.

14.Congressional Budget Office. American Health Care Act. [Online] March 13, 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52486.

15.Cox, Cynthia, et al. 2017 Premium Changes and Insurer Participation in the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplaces. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] November 1, 2016. http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/2017-premium-changes-and-insurer-participation-in-the-affordable-care-acts-health-insurance-marketplaces/.

16.Cox, Cynthia, et al. Analysis of 2015 Premium Changes in the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplaces. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] January 6, 2015. http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/analysis-of-2015-premium-changes-in-the-affordable-care-acts-health-insurance-marketplaces/.

17.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health Plan Choice andPremiums in the 2017 Health Insurance Marketplace. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Online] October 24, 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-plan-choice-and-premiums-2017-health-insurance-marketplace.

18. Avery, Kelsey, et al. Health Plan Choice and Premiums in the 2016 Health Insurance Marketplace. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [Online] October 30, 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-plan-choice-and-premiums-2016-health-insurance-marketplace.

19. Office of the Assistance Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Addendum to the Health Insurance Marketplace Summary Enrollment Report for 2014. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Online] May 1, 2014. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/addendum-health-insurance-marketplace-summary-enrollment-report.

20. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health Insurance Marketplace 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Online] March 2015, 10. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-marketplace-2015-open-enrollment-period-march-enrollment-report.

21. —. Addendum to the Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Online] March 11, 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/188026/MarketPlaceAddendumFinal2016.pdf.

22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Online] March 15, 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Marketplace-Products/Plan_Selection_ZIP.html.

23. Kaiser Family Foundation. Number of Insurers Participating in the Individual Health Insurance Marketplaces. [Online] 2017. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/number-of-issuers-participating-in-the-individual-health-insurance-marketplace.

24. State of Alaska. Affordable Care Act State Innovation Waiver. [Online] November 22, 2016. https://aws.state.ak.us/OnlinePublicNotices/Notices/View.aspx?id=183687.

25. State of Tennessee. Access Tennessee Act of 2006 (2016 Public Chapter 867). [Online] July 6, 2006. http://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/104/Chapter/PC0867.pdf.