Key Takeaways

- Governments often subsidize sports venues in an effort to attract or retain professional teams and large events – which they expect to generate other benefits.

- Pro sports stadiums rarely create enough new economic activity to offset public subsidies, according to most economists and researchers.

- New venues can generate net benefits if they create new economic activity, but in most cases, they simply redistribute existing economic activity within a region.

- New venues may create other costs for state and local governments, residents, and businesses not always evident in the price of the initial subsidy.

- Every public investment, including venue subsidies, comes with an opportunity cost – that is, the impact of not using taxpayer dollars for something else.

- Pro sports venues may also generate benefits that are hard to quantify – such as civic pride or cumulative effects in combination with other local attractions.

- Since 2021, state and local officials have committed or planned to commit $1.8 billion in taxpayer-funded subsidies for at least five pro sports venues across Tennessee.

- That figure includes $1.5 billion for a proposed new, covered Titans stadium in Nashville. If approved, this would be the largest taxpayer subsidy for an NFL stadium on record.

Note: The stadium subsidy numbers have changed since this report was published. This report does not reflect those changes.

In the last two years, state and local policymakers approved public subsidies for five professional sports venues‡ in Tennessee – including two of the 13 now operating and replacements for three others. In this report we answer common questions about these stadium deals, how they’re paid for in Tennessee and beyond, and whether they’re worth it. Ultimately, each stadium deal is unique. Citizens and policymakers at various levels of government may see it from different perspectives and should weigh the pros and cons of each one individually.

See Appendix Table 1 for a complete list of professional sports venues‡ either planned or currently operating in Tennessee.

Why Do Governments Subsidize Pro Sports Venues?

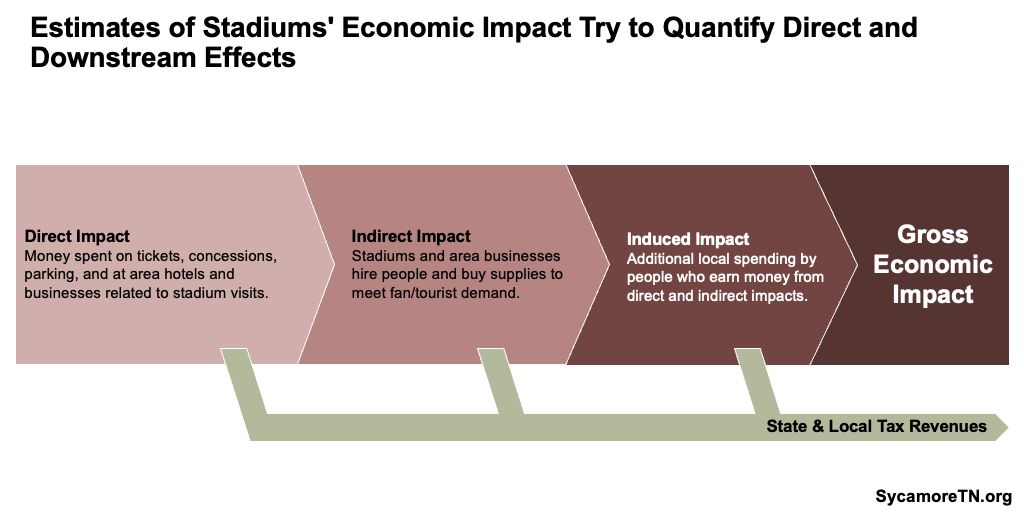

Governments often subsidize sports venues in an effort to attract or retain professional teams and large events – which they expect to generate financial benefits. Economic estimates that support these projects often point to consumer spending and other economic activity tied to related events, tourism, and development. That spending might support local businesses and workers, who in turn spend more themselves. To the extent this commerce stays in the region, it’s subject to state and local sales taxes that can support other public investments (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Sports teams and the exposure they bring can also create intangible goods that are harder to quantify – like civic pride. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Pro sports can serve as a source of entertainment, help to socialize new residents, and contribute to a sense of shared community. (6) As a result, local fans who feel a strong affinity for their hometown team may encourage government officials to use public funds to keep that team nearby and playing in a state-of-the-art venue. Speaking in 1996 of the deal that brought the Tennessee Titans from Houston, Nashville’s mayor said, “You don’t have to be a financial wizard to figure out that this does not pay out very well. […] But there are so many intangible reasons.” (7) While this report focuses on the easier-to-quantify economics of stadium subsidies, policymakers should not discount the role of these potential intangible benefits.

Subsidies often result from the competition between cities (and sometimes states) for one of the limited number of pro sports teams. For example, the NFL controls how many franchises exist and has kept the number at 32 teams since 2002. When demand exceeds this controlled supply, teams have more leverage to get concessions from current or would-be host cities. Recent examples of NFL teams relocating for a new, publicly subsidized stadium or threatening to move before getting one in their current city include the Raiders, Vikings, Falcons, 49ers, and – in 1997 – the Titans. (8) (9) (10) (11)

How Do Tennesseans Pay for Stadium Subsidies?

In Tennessee, governments typically subsidize new stadiums by taking on debt in the form of bonds and diverting future tax collections to pay those debts. Revenue streams used to fund these subsidies in Tennessee include:

- Venue Taxes – Governments can earmark taxes collected at the venue to pay for its construction and/or maintenance. For example, state sales tax collected at Titans’ games helps to pay off the $55 million in bonds the state took out for construction on the team’s current stadium. (12) Similarly, $225 million in municipal bonds for the Nashville Soccer Club’s new GEODIS Park will be paid off using local sales taxes collected on site. (13)

- Taxes on Specific Goods/Services – Governments can levy taxes on specific goods and services to pay for stadium subsidies. For example, Nashville recently got state approval to increase its local tax on all hotel and motel stays – but only for the purpose of subsidizing the construction and maintenance of a new, roofed stadium for the Titans. (14)

- General Fund Taxes – Governments can also promise to cover debt costs from their general operating funds. At the state level, the main general fund revenue streams are the statewide sales, franchise, and excise taxes. At the local level, the main revenue streams are local sales and property taxes. For example, the state’s general fund will help pay off a $500 million bond the state plans to take out for construction of a new, enclosed Titans stadium. (15)

State and local governments can also subsidize venues with direct grants, typically from their General Fund. Unlike bond-financed subsidies, these payments carry no long-term debt service obligations. Recent examples from the state-level include $13.5 million for a new, relocated ballfield for the Tennessee Smokies and $17 million for raceway grants. (16) (15) At the local level, Metro Nashville made a $12.3 million grant toward the construction of Bridgestone Arena in addition to issuing $155 million in bonds. (17)

What Stadiums Have Tennesseans Subsidized Recently?

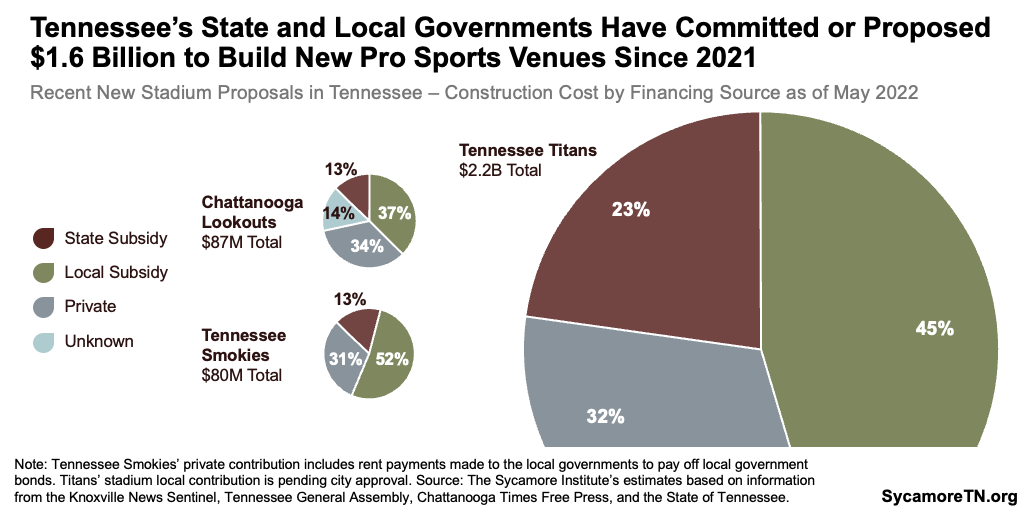

Since 2021, state and local lawmakers have approved taxpayer-funded subsidies for at least five pro sports venues in Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga. Officials have committed or signaled a plan to commit at least $1.6 billion for three new stadiums (Figure 2) and over $220 million for two existing venues (excluding racetracks‡). Together, these funds will subsidize facilities for five of the state’s 15 professional sports teams (Appendix Table 1). Additional funding outside of these estimates are also provided by local and state government for surrounding public infrastructure and ongoing maintenance costs, among other items. (18) (19)

Figure 2

New Venues

- $1.5 Billion for New Tennessee Titans Stadium: Lee and state lawmakers recently approved $55 million in recurring debt costs for $500 million in bonds toward a potential $2.2 billion replacement for the 23-year old Nissan Stadium.(20) The Titans and NFL plan to contribute $700 million, which appears to leave the city of Nashville responsible for the other $1 billion. (21) (22) The city will use at least three different revenue streams to pay its share. First, a new state law lets Nashville increase from 6% to 7% its local tax on all hotel stays. (14) In 2021, the General Assembly also approved a 30-year subsidy directing local sales tax collections and up to $10 million per year in state sales tax from inside the stadium and nearby development to help pay for either renovations or new construction. (23)

- $55 Million for New Tennessee Smokies Ballpark: Construction is underway for a new minor league baseball stadium and surrounding development in Knoxville, where the Tennessee Smokies will move from their current home at Smokies Stadium near Sevierville. In 2021, the state gave a $13.5 million grant for the new $80 million ballpark.(16) Another $130,000 per year in state sales tax collected at the venue would be used to pay off stadium construction debt. (24) (25) Knoxville and Knox County will contribute about $42 million in total, funded at least in part from local sales and property taxes collected in and around the ballpark. The Smokies’ owner will provide nearly $6 million, and the team’s rent payments will cover another $19 million. Most recently, the city and county approved another $14 million – not in these totals – to improve the infrastructure around the new ballpark, including new paving, landscaping, sewer, and sidewalks. (18)

- $43 Million for New Chattanooga Lookouts Ballpark: State lawmakers recently diverted at least $110,000 per year in state sales tax collected at a proposed new $86.5 million minor league baseball stadium in Chattanooga to replace AT&T Field. (26) (26) The city and Hamilton County will contribute about $32 million from venue-related property tax collections and other general fund revenues. Almost $30 million will come from the team’s lease payments and donated land. So far, the state has not funded the local governments’ request for a $13.5 million construction grant and another $7.3 million for related environmental remediation (not included in the total construction cost). (27)

Other Venues and Related Infrastructure

- $200 Million for Bridgestone Arena: Last year, the state extended an annual $10 million subsidy for the arena where Nashville’s professional hockey team has played since 1998. Funded by state sales taxes collected at the venue, the subsidy was set to expire in 2029 but will now continue through 2049. (29) (12)

- $5 Million for CHI Memorial Stadium: Early this year, state lawmakers approved a $5 million public infrastructure grant for the already-completed minor league soccer stadium home to the Chattanooga Red Wolves. (32)

- $17 Million for a Raceway: The state’s approved budget for FY 2023 included $17 million for Tennessee’s Department of Tourist Development for grants to raceways.(15) Although details are not clear, media reports suggest the grant would fund the improvements needed to host NASCAR races at the Nashville Fairgrounds Speedway. (30) (31)

Does Tennessee’s Approach Differ from Other States?

Tennessee’s approach to funding stadiums is in line with many other parts of the country. (33) State and local governments in the United States have a long history of subsidizing major league sports. From 1990 to 2010, 84 new venues were built for teams in professional sports leagues, with public financing providing a significant portion of the cost. (34) While most sports stadiums were privately funded until 1953, stadium and arena costs were 90% publicly funded between 1960-1984. (35) (36) Additionally, the average public financial contribution to sports facility costs was $270 million for venues built between 2000 and 2017. (35) Similar debates about the economic impact and trade-offs of paying for stadiums have occurred across most major cities and smaller towns looking to attract or retain teams.

Tentative Details on Potential New Titans Stadium

The agreement that initially attracted the Titans to Nashville makes the city legally responsible for maintaining a “first-class” facility – which is loosely defined. That lease between the Metro Sports Authority in Nashville and the Titans requires the city to pay costs that keep Nissan Stadium in good condition and comparable to other venues of similar age nationally. (37) (38) (39) Each year, the city has allocated $1 million for this purpose. (19)

In early 2022, discussions to renovate the Titans’ current stadium shifted toward building a brand-new venue. The switch reportedly came after a significant jump in the estimated cost of renovating the team’s current home. A 2017 analysis put the cost of required capital improvements at $293 million over the next two decades. (40) In the last six months, news reports have mentioned estimates to renovate the existing stadium that range from $600 million to $1.8 billion. (41) (21)

Titans owners, Nashville, and the state may all share the cost of building a new stadium – most recently estimated at $2.2 billion, and the city aims to shift maintenance costs to the team. (42) The details of the deal as it currently stands are discussed above.

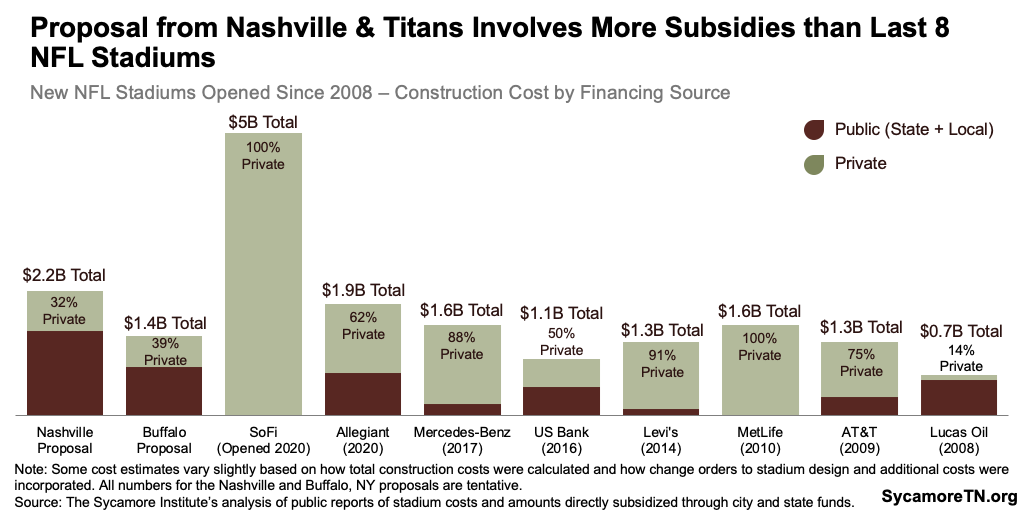

While nothing is final, $1.5 billion in taxpayer-funded subsidies for the proposed new Titans venue would be the largest pro football stadium subsidy on record in the U.S. (Figure 3). The share of direct public subsidization of NFL stadiums has decreased over time, with one study estimating that taxpayers paid about 75% of construction costs between 1987 and 2008 but just 25% from 2009 to 2017. (46) As outlined in news reports, the tentative share of public financing for a new Titans stadium (about 68%) aligns more closely with venues built in the late 1990s and early 2000s than those built more recently. Figure 3 shows publicly reported direct subsidies for stadium construction but does not include indirect subsidies such as the donation of public land, maintenance costs, and additional infrastructure often included in stadium deals. Often, municipal bonds used by private financiers and indirect subsidies were not disclosed in NFL stadium deals. (43) (22) (44)

Figure 3

State and local taxpayers and fans paid the $264 million to build the current stadium, which opened in 1999. The sale of personal seat licenses covered $23 million, the state contributed $55 million, and Metro Nashville put up the rest. Tennessee directs state sales taxes collected at Titans games through FY 2029 to repay its share of the debt, while the city relies on a mix of local sales and ticket taxes collected at games and hotel taxes. (22)

What Economic Impact Do Stadium Subsidies Have?

Pro sports venues rarely create enough new economic activity to offset public subsidies, according to most economists and researchers. (47) (48) (1) (49) (3) (50) (51) (52) Economic projections associated with these developments tend to focus on gross benefits rather than net benefits and do not often account for (2) (47):

- Economic activity that would take place anyway, even without the project.

- The share of project-related economic activity that exists or occurs outside of the local economy.

- The full costs of the completed project – for example, cost overruns, surrounding infrastructure, maintenance, and law enforcement.

- Opportunity costs (i.e., other investments a community could have made with the same money).

Differentiating New Projects from Replacements

Most evaluations of stadiums’ financial benefits focus on the impact of completely new venues instead of renovations or replacements. Many benefits associated with new NFL stadiums come mainly from the arrival of a new team. (3) It can be harder to evaluate the economic impact of a renovated or replacement stadium because the upside is largely limited to events that the existing venue cannot host. For example, the Titans’ current stadium often hosts concerts and other events in addition to pro football games. The team reportedly estimates that a new, enclosed stadium could attract 15 additional events per year, which proponents argue might include major events like a Super Bowl or Final Four tournament. (53) (54)

Tennessee is currently looking to replace three pro sports venues that are each just over 20 years old. Nissan Stadium in Nashville, AT&T Field in Chattanooga, and Smokies Stadium in Sevierville are all up for replacement. While the Nashville stadium will likely be torn down, the fate of the others is unclear. Public subsidies for the Nashville and Sevierville stadiums are still being paid off. (55) (56) In the prior 25 years, two Tennessee pro sports venues were replaced – Greer Stadium in Nashville and Tim McCarver Stadium in Memphis (Appendix Table 1). Both were nearly 40 years old at the time of their closure and demolition.

Redistribution, Recirculation, and Leakage

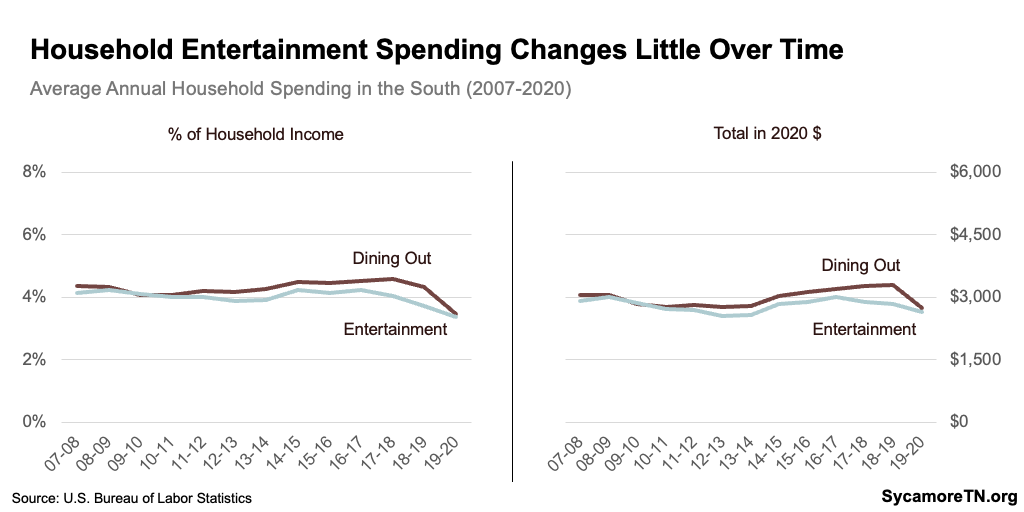

New venues can generate net benefits when they create new economic activity, but most largely redistribute existing activity within a region. People generally have fixed entertainment budgets. For example, households in the South consistently spend about 4% of their incomes on entertainment – or roughly $3,000 a year, on average (Figure 4). Locals who spend money at and around a new venue may otherwise have spent it on different area entertainments or – for travelers from within the region – in nearby communities.(1) (2) (49) (52) Even distance-travelers’ spending isn’t always new, since out-of-town attendees at games or performances often have other reasons driving their visit to that city. In other words, much of this economic activity would happen in the same region with or without a publicly subsidized new venue. (3) (50) (47) (52)

Figure 4

Consumer spending associated with pro sports venues often “leaks” out of the local economy. Much of the direct spending on major league sports ultimately goes to home team owners and players, visiting teams, and the leagues themselves. Even with local owners, players, and coaches, they often put significant money into non-local investments, spend it in other cities, or owe it as federal income tax. (2) (3) (50) (47) States with their own income taxes may see noticeable revenue gains from the presence of high-income personnel, but Tennessee does not have an income tax. (57)

These effects will look different based on the city, region, and state of the venue in question. For example, a typical game or concert in Nashville may attract in-state visitors from nearby communities who might not otherwise visit the city. This would represent new economic activity for Nashville but not for the larger region or state. While we are not aware of specific research on the topic, events in border cities like Memphis, Chattanooga, or Bristol might also pull into Tennessee more economic activity that would have occurred elsewhere.

Cumulative Effects

When combined with other tourist attractions, new sports venues may have a cumulative positive effect on a local economy not captured in studies looking at marginal impact. In other words, the whole of a city or region’s tourist destinations – including a new stadium – may be greater than its individual parts. A new stadium may be one of many attractions that together help to create a desirable tourist/entertainment hub that attracts new economic activity to an area. Studies focused on a new stadium’s marginal economic impact generally will not account for these combined effects.

Employment Effects

Stadium construction and renovations can temporarily boost local employment, depending on the circumstances. Large, publicly funded building projects are often used as a way to stimulate the economy during economic recessions, when the demand for construction usually drops. However, there is disagreement as to whether those projects produce the swift economic benefits policymakers seek. (60) The benefits when the economy is strong are even less clear – especially when the construction industry faces supply chain issues, labor shortages, rising costs, and booming demand. (61)

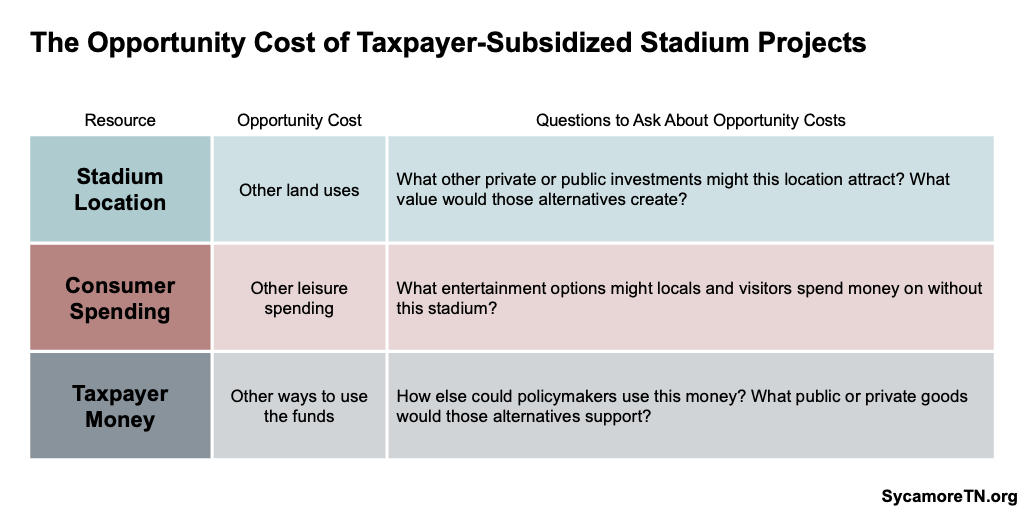

New spending in a region can also create permanent jobs, but tourism-related jobs tend to pay relatively low wages and have become increasingly hard to fill. Many of the jobs available at sports venues and nearby leisure and hospitality businesses are temporary, part-time, and/or low-paying. (52) By the time a new Titans stadium would open, the labor market will likely look very different than it does today. However, employers in this sector have struggled to fill open jobs in the wake of economic disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. As of April 2022, 8.9% of available leisure and hospitality jobs in the U.S. were unfilled – one of the highest vacancy rates of any industry (Figure 5). (59)

Figure 5

Accounting for Other Expenses

Pro sports venues may create additional costs for state and local governments, residents, and businesses beyond any direct subsidies for venue construction. For example, governments often build or improve roads and other infrastructure to support large new venues. (2) Some – like Metro Nashville did with the Titans current stadium – agree to pay ongoing maintenance costs for a facility. Other costs to taxpayers can include expenses for infrastructure maintenance, garbage and sanitation, security, and facility enhancements. (3) (47) Events at the venue may also create harder-to-quantify costs and inconveniences for local residents like increased traffic or quality-of-life concerns. (52)

Large, one-time events that attract significant out-of-town spending can also carry costs and additional subsidies that might outweigh the benefits. Major events like the Super Bowl are often pitched as a reason for public investment in pro sports venues, and such events do sometimes follow. However, there is debate over their economic impact based on which metrics people cite and how they compare to baseline levels. (62) (63) In addition to new revenue, examples of potential costs include more security personnel, transportation for attendees, parking lot construction, development of nearby land, and event-specific tax breaks. Some Super Bowl host cities report favorable outcomes, while others have reported losing money. (64) The amount of new economic activity may also depend on a city’s level of activity before the event. It’s possible that a city with little tourism and high hotel vacancy rates might see a bigger boon from large one-time events than cities that consistently attract visitors.

Opportunity Costs

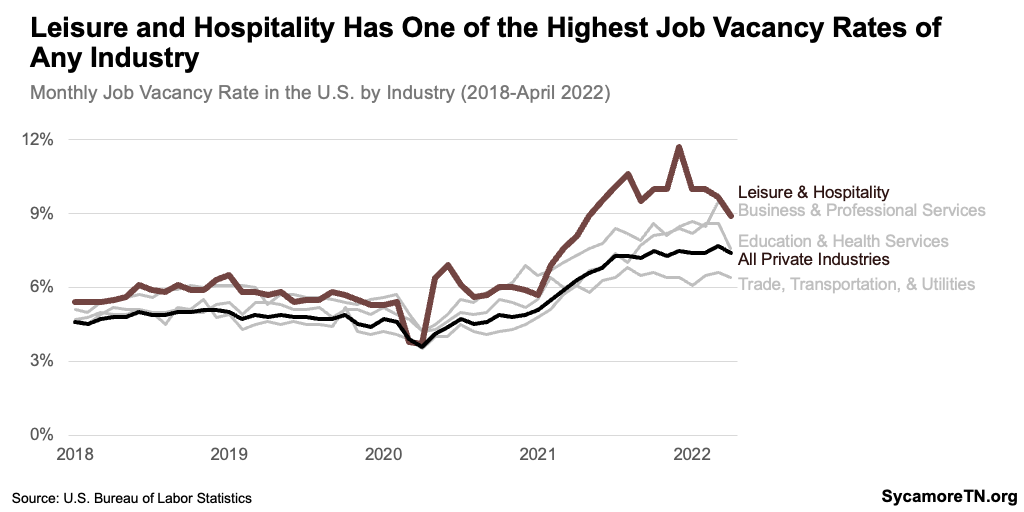

Every public investment has an opportunity cost – other potential uses for the money that the chosen use takes off the table (Figure 6). A dollar spent on pro sports venues cannot also fund basic infrastructure, education, public safety, or tax relief – and vice versa. (2) (1) (49) (50) (47) (52) A full estimate of a public subsidy’s economic benefit would weigh it against the potential benefits of other plausible uses.

Figure 6

Even new or dedicated revenue streams that repay stadium debts represent public subsidies with opportunity costs. Governments often use taxes collected on site to pay their debts from building a stadium, which some view as a user fee on the fans. In the absence of a stadium, much of that taxable spending would likely have occurred elsewhere in a city or region. And without subsidies to pay off, the revenue would flow instead to a state or city’s general fund to support routine public services. In contrast, the typical new business owner does not get to apply the sales taxes they collect towards their rent or mortgage. Ultimately, of course, the opportunity cost of diverting any new revenue also depends on many other factors discussed in this report.

Dedicating publicly owned land and other resources (e.g., enhanced security, new infrastructure) to stadium uses can also have trade-offs, depending on desirability for other purposes. For example, some stadiums are built in an effort to revitalize surrounding areas that have little economic activity, while others use land that already has high development potential. Using desirable or high-value land for subsidized stadium developments can limit other activities – like businesses, housing, or other entertainment options – that might have located there with or without subsidies.

Parting Words

In the last 18 months, state and local policymakers have approved a variety of public subsidies for at least five professional sports venues across Tennessee. Every deal like this is unique and has a complex set of considerations and trade-offs that officials at the state and local level may see from different perspectives. When evaluating these proposals, policymakers at all levels of government should carefully consider the potential benefits and costs.

‡ Our counts and the list of professional sport venues do not include racetracks because of the number and diversity of professional racing categories and venues, which often only host a single race each year.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Wolla, Scott A. The Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Online] May 2017. https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/page1-econ/2017-05-01/the-economics-of-subsidizing-sports-stadiums/.

- Zaretsky, Adam. Should Cities Pay for Sports Facilities? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Online] April 1, 2001. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/april-2001/should-cities-pay-for-sports-facilities.

- Siegfried, John and Zimbalist, Andrew. The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities. Journal of Economic Perspectives. [Online] Summer 2000. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.14.3.95.

- Sack, Kevin. Can Nashville Say No to NFL Team? Maybe. [Online] May 3, 1996. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/03/us/can-nashville-say-no-to-nfl-team-maybe.html.

- DeMause, Neil. Why Do Mayors Love Sports Stadiums? The Nation. [Online] July 27, 2011. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/why-do-mayors-love-sports-stadiums/.

- Rosentraub, Mark S, Tsvetkova, Alexandra and Swindell, David. Public Dollars, Sports Facilities, and Intangible Benefits: The Value of a Team to a Region’s Residents and Tourists. Journal of Tourism. [Online] 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alexandra-Tsvetkova/publication/261251545_Public_Dollars_Sport_Facilities_and_Intangible_Benefits_The_Value_of_a_Team_to_a_Region%27s_Residents_and_Tourists/links/0deec533b1e65bec76000000/Public-Dollars-Sport-Facilitie.

- Simers, T.J. Nashville Joins Major Leagues With a Big ‘Yes’ Vote on Oilers . Los Angeles Times. [Online] September 1, 1996. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-09-01-sp-39823-story.html.

- Kerr, Jeff. Las Vegas Raiders Latest NFL Franchise to Change Cities: Here’s a Look at All 11 Who’ve Done It. CBS Sports. [Online] February 4, 2020. https://www.cbssports.com/nfl/news/las-vegas-raiders-latest-nfl-franchise-to-change-cities-heres-a-look-at-all-11-whove-done-it/.

- Belson, Ken. NFL Warns That Vikings Could Move. The New York Times. [Online] April 20, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/20/sports/football/nfl-warns-that-vikings-could-move.html.

- Florio, Mike. Withough a New Stadium, Falcons Will Move (Elsewhere in Atlanta). NBC Sports. [Online] February 13, 2013. https://profootballtalk.nbcsports.com/2013/02/13/without-a-new-stadium-falcons-will-move-elsewhere-in-atlanta/.

- Upton, John. The San Francisco Retreat. Slate. [Online] January 31, 2013. https://slate.com/culture/2013/01/49ers-santa-clara-why-didnt-san-francisco-try-harder-to-keep-its-football-team-from-moving-out.html.

- Fiscal Review Committee Staff. Fiscal Note: HB 157 – SB 481. [Online] February 25, 2021. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/112/Fiscal/HB0157.pdf.

- Bonn, Kyle. Nashville SC Stadium GEODIS Park: History, Capacity, Debut as Largest Soccer-Specific Stadium in USA is Open for MLS Play. The Sporting News. [Online] May 2, 2022. https://www.sportingnews.com/us/soccer/news/nashville-sc-stadium-geodis-park-history-capacity-debut-soccer-usa/orlhys2itcr3j0jnpjaxzl6x.

- Tennessee General Assembly. House Finance, Ways, and Means Amendment 1 to HB 681/SB 421. [Online] May 2022. Accessed from https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/default.aspx?BillNumber=HB0681&GA=112.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 1130 (2022). [Online] June 1, 2022. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/112/pub/pc1130.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 454 (2021). [Online] 2021. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/112/pub/pc0454.pdf.

- The Metropolitan Government of Nashville & Davidson County. Bridgestone Arena. Nashville.gov. [Online] [Cited: May 26, 2022.] https://www.nashville.gov/departments/sports-authority/bridgestone-arena.

- Whetstone, Tyler. Taxpayer’s Front $14M to Spruce Up Neighborhood Around Knoxville’s New Smokies Stadium. Knoxville News Sentinal. [Online] February 8, 2022. https://www.knoxnews.com/story/news/politics/2022/02/09/14-million-spruce-up-neighborhood-around-knoxville-smokies-stadium/6661692001/.

- The Metropolitan Government of Nashville & Davidson County. FY 2022 Operating Budget. [Online] July 2021. https://www.nashville.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/FY-2022-Operating-Budget-Book-linked.pdf?ct=1637354354.

- Friedman, Adam. Senate Panel Cuts Titans Stadium From State Budget as Lee, Lawmakers Clash Over Priorities. The Tennessean. [Online] April 21, 2022. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/2022/04/21/senate-removes-titans-stadium-budget-lee-and-lawmakers-clash/7356826001/.

- Mazza, Sandy and Stephenson, Cassandra. Titans: $2.2B New NFL Stadium a Better Value for Nashville than Nissan Stadium Renovations. The Tennessean. [Online] May 19, 2022. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/2022/05/19/tennessee-titans-say-new-nfl-stadium-would-best-value/9813062002/.

- County, The Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson. FY 2022-23 through FY 2027-28 Mayor’s Draft. Nashville.gov. [Online] May 14, 2022. https://www.nashville.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/FY23_CIB_MayorsDraft.pdf?ct=1652578361.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 401 (2021). [Online] May 2021. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/112/pub/pc0401.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 422 (2021). [Online] 2021. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/112/pub/pc0422.pdf.

- Fiscal Review Committee Staff. Fiscal Memorandum: SB 783 – HB 1204. Tennessee General Assembly. [Online] April 19, 2021. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/112/Fiscal/FM1208.pdf.

- Tennessee General Assembly. HB 2609 – SB 2890. [Online] 2022. https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/default.aspx?BillNumber=HB2609&GA=112.

- Pare, Mike. Chattanoogans See How New Ballpark Helped Revitalize Part of a South Carolina City. Chattanooga Times Free Press. [Online] March 19, 2022. https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2022/mar/19/chattanoogans-ballpark/565403/#/questions/.

- Fiscal Review Committee Staff. Fiscal Memorandum: HB 2609-SB 2890. [Online] April 12, 2022. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/112/Fiscal/FM2764.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 591 (2021). [Online] 2021. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/112/pub/pc0591.pdf.

- Elliott, Stephen. Lee Proposes Millions for NASCAR, Titans. Brentwood Home Page. [Online] March 29, 2022. https://www.williamsonhomepage.com/brentwood/lee-proposes-millions-for-nascar-titans/article_2590359e-6565-5982-8434-6e0f53e23349.html.

- Rau, Nate. Fairgrounds Racetrack Renovation in Holding Pattern. Axios Nashville. [Online] March 30, 2022. https://www.axios.com/local/nashville/2022/03/30/fairgrounds-racetrack-renovation-in-holding-pattern.

- Pare, Mike. $200 Million East Ridge Project Will Benefit From State, County Funds. Chattanooga Times Free Press. [Online] May 4, 2022. https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/business/aroundregion/story/2022/may/04/200-millieast-ridge-project-will-benefit-stat/568357/.

- Brown, Eliot. Texas Rangers’ Planned New Arlington Stadium Shows Ballparks’ Shorter Lifespan. The Wall Street Journal. [Online] June 17, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/texas-rangers-planned-arlington-stadium-shows-ballparks-shorter-lifespan-1466181483.

- Long, Judith Grant. Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities. s.l. : Routledge, 2012. https://www.routledge.com/Public-Private-Partnerships-for-Major-League-Sports-Facilities/Long/p/book/9780415629799.

- Mayer, Martin and Cocco, Adam. Pandemic and Sport: The Challenges and Implications of Publicly Financed Sporting Venues in an Era of No Fans. October 30, 2020, Public Works Management and Policy, Vol. 26, pp. 26-33. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1087724X20969161.

- Howard, Dennis and Crompton, John. Financing Sport: Fourth Edition. s.l. : FiT Publishing, 2018. https://fitpublishing.com/books/financing-sport.

- Rau, Nate. Scoop: Titans Exploring New Stadium. Axios Nashville. [Online] February 17, 2022. https://www.axios.com/local/nashville/2022/02/17/tennessee-titans-new-stadium.

- Masters, Julia and Sichko, Adam. Titans Study: Metro Facing $1.8B Bill to Upgrade Nissan Stadium. Nashville Business Journal. [Online] May 19, 2022. https://www.bizjournals.com/nashville/news/2022/05/19/titans-metro-stadium-cost.html.

- Sutton, Caroline. Titans: $1.8B Needed to Maintain Nissan Stadium Through 2039, But New Stadium Could Cost $2.2B. News Channel 5. [Online] May 20, 2022. https://www.newschannel5.com/sports/titans-1-8b-needed-to-maintain-nissan-stadium-through-2039-but-new-stadium-could-cost-2-2b.

- Garrison, Joey. Nashville’s Nissan Stadium, Bridgestone Arena Need $477M in Upgrades, New Reports Say. The Tennessean. [Online] May 18, 2017. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/2017/05/18/nashvilles-nissan-stadium-bridgestone-arena-need-477m-upgrades-new-reports-say/101829430/.

- Gallagher, Michael. Lee Says State Open to Helping Titans With Stadium Project. Nashville Post. [Online] March 23, 2022. https://www.nashvillepost.com/sports/titans/lee-says-state-open-to-helping-titans-with-stadium-project/article_f929c8c2-aae0-11ec-91cb-eb750b5a33fc.html.

- Cooper, John. Mayor Cooper: Nashville’s Football Stadium Will Not Be Taxpayer Burden Under New Plan. The Tennessean. [Online] May 12, 2022. https://www.tennessean.com/story/opinion/2022/05/12/mayor-cooper-nashvilles-new-football-stadium-not-burden/9732484002/.

- Watson, Stephen. Pay to Play: How 21 NFL Stadiums Have Been Financed. Buffalo News. [Online] September 5, 2021. https://buffalonews.com/news/local/pay-to-play-how-21-nfl-stadiums-have-been-financed/article_319a3686-0c28-11ec-a568-dbcbdd817498.html.

- Ewing, Claudine. Public Dollars Often Used for New Sports Stadiums, Arenas. WGRZ News. [Online] August 2, 2021. https://www.wgrz.com/article/news/local/public-dollars-often-used-for-new-sports-stadiums-arenas/71-ee6cab82-418f-41ce-944a-6e875ac39460.

- Ferre-Sadurni, Luis. Buffalo Bills Strike Deal for Taxpayer-Funded $1.4 Billion Stadium. The New York Times. [Online] March 28, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/28/nyregion/buffalo-bills-stadium-deal.html.

- Baumann, Robert, Matheson, Victor and O’Connor, Debra. Hidden Subsidies and the Public Ownership of Sports Facilities: The Case of Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara. Worcester : College of the Holy Cross, Department of Economics, Massachusetts. https://crossworks.holycross.edu/econ_working_papers/186/.

- Bradbury, John Charles, Coates, Dennis and Humphreys, David R. The Impact of Professional Sports Franchises and Venues on Local Economies: A Comprehensive Survey. SSRN. [Online] January 31, 2022. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4022547.

- Cockrell, Jeff. What Economists Think about Public Financing for Sports Stadiums. Chicago Booth Review. [Online] February 1, 2017. https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/what-economists-think-about-public-financing-sports-stadiums.

- Farren, Michael D. Stadium Subsidies are a Terrible Investment for Taxpayers. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. [Online] August 20, 2019. https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/quotable-quotes-stadium-subsidies-are-terrible-investment-taxpayers.

- Coates, Dennis and Humphreys, Brad R. Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Subsidies for Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Mega-Events? Economic Journal Watch. [Online] September 2008. (pdf download) https://econjwatch.org/file_download/222/2008-09-coateshumphreys-com.pdf.

- Agha, Nola and Rascher, Daniel. Economic Development Effects of Major and Minor League Teams and Stadiums. Journal of Sports Economics. [Online] November 28, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1527002520975847.

- Crompton, John L. Economic Impact Analysis of Sports Facilities and Events: Eleven Sources of Misapplication. Journal of Sports Management. [Online] https://college.agrilife.org/rptsweb/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2020/08/a65494313458a3f1ca55a89d7afaf3c74ac9.pdf.

- Moraitis, Mike. Report: $500M Proposal for New Titans Stadium Calls for Enclosed Venue. USA Today Sports. [Online] March 28, 2022. https://titanswire.usatoday.com/2022/03/28/tennessee-titans-new-stadium-proposal-enclosed-report/.

- Friedman, Adam, Stephenson, Cassandra and Mazza, Sandy. Exclusive: New Nashville NFL stadium could exceed $2B and be ready by 2026. The Tennessean. [Online] April 14, 2022. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/davidson/2022/04/15/new-nashville-nfl-stadium-could-exceed-2-b-and-ready-2026/7317699001/.

- Simlot, Vinay. What Happens to the Baseball Stadium in Kodak if the Tennessee Smokies Leave? WBIR 10 News. [Online] November 21, 2021. https://www.wbir.com/article/news/local/sevierville-sevier/what-happens-to-stadium-in-kodak/51-17543609-61c2-4c68-9ce8-c36322dccf32.

- Paschall, David. Lookouts Must ‘Start Over’ for Pro Baseball to Remain in Chattanooga. Chattanooga Times Free Press. [Online] February 26, 2022. https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2022/feb/26/lookouts-start-over/564116/#/questions/.

- AECOM. Preliminary Buffalo Bills Stadium Analysis. [Online] November 2021. https://esd.ny.gov/sites/default/files/news-articles/ESD-Bills-Stadium-Analysis-Summary-FINAL-11-1-21.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Expenditure Surveys. [Online] 2022. https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/cex/concepts.htm.

- —. Economic News Release: Job Openings Levels and Rates by Industry and Region, Seasonally-Adjusted. [Online] March 29, 22. [Cited: April 19, 2022.] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.t01.htm.

- Copeland, Claudia, Levine, Linda and Mallett, William J. The Role of Public Works Infrastructure in Economic Recovery. Congressional Research Service. [Online] September 21 2011. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R42018.pdf.

- Horan, Kyle. Builders Association CEO Thinks Construction Prices May Stabilize in Future . News Channel 5. [Online] September 18, 2021. https://www.newschannel5.com/news/builders-association-ceo-thinks-construction-prices-may-stabilize-in-future.

- Cameron, Steve and Kim, Gene. Why Hosting the Super Bowl Isn’t Worth It, According to an Economist. Business Insider. [Online] February 5, 2021. https://www.businessinsider.com/super-bowl-nfl-football-hosting-cost-worth-host-cities-2019-2.

- Kopsky, Claire. Economist: Pros May Not Outweigh Cons of Building New Titans’ Stadium. News Channel 5 Nashville. [Online] April 12, 2022. https://www.newschannel5.com/news/economist-pros-may-not-outweigh-cons-of-building-new-titans-stadium.

- PlayNY Team Editorial. Is It Financially Worth It For a City to Host the Super Bowl? Depends On Who You Ask. PlayNY. [Online] February 7, 2022. https://www.playny.com/cost-of-hosting-super-bowl/.

Featured image adapted from photo by xetark