Last week, the federal government approved a 10-year renewal of TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid program, which was set to expire on June 30, 2021. (1) (2) (3) It sets several new precedents for the state-federal Medicaid partnership – including never-before-approved flexibilities and the opportunity to draw down new federal dollars without additional state spending.

This brief will help stakeholders understand the details of the agreement and what it could mean for Tennessee. After laying out the mechanics of TennCare III, the analysis compares it to a renewal of the previous waiver and summarizes main points of contention and next steps.

Key Takeaways

- Six key differences between the new TennCare III agreement and what a typical TennCare II renewal might have looked like:

-

- Tennessee may get more federal Medicaid dollars without spending any new state money.

- TennCare can limit coverage of some prescription drugs – a common practice for private insurance and Medicare but never before allowed in Medicaid.

- The state would not need further federal approval for any changes that keep TennCare eligibility and benefits at or above end-of-2020 levels.

- Due to changes in federal policy, the new federal funding cap may pose less financial risk to Tennessee than a renewal of the existing program.

- The new shared savings provisions add to the state’s existing financial incentive to reduce TennCare spending.

- If policymakers want to roll back TennCare III, it could take longer than prior waivers.

- TennCare III creates an unprecedented and complex set of new incentives and opportunities for state policymakers. It also creates new uncertainties for people enrolled in the program.

- TennCare III does not address or preclude a comprehensive expansion of eligibility to all adults with incomes under 138% of poverty if state policymakers choose to pursue that.

- The Biden administration could rescind the approval, but the Trump administration has taken steps to lengthen that process. At the same time, the program will almost certainly face legal challenges in state and federal court.

The Mechanics of Tennessee’s New Medicaid Waiver

The federal government recently approved TennCare III, which renews the program for 10 years and integrates much of Tennessee’s “modified block grant” proposal. The prior TennCare waiver (i.e. TennCare II) was set to expire on June 30th. State officials are calling the changes to existing federal funding limits a “block grant” or “modified block grant” while federal regulators use the terms “aggregate cap” and funding “target.” In this brief, we refer to it as TennCare III’s federal funding cap or limit.

Under TennCare III, federal funding will be limited by an aggregate cap based on state-specific costs, national trends, and certain changes in enrollment. (1) Since its inception in 1994, TennCare has been subject to a federal funding limit known as the budget neutrality cap (see text box for more information). The federal government covers roughly 65% (i.e. federal medical assistance percentage or FMAP) of Tennessee’s Medicaid costs up to that limit. TennCare has consistently remained below the limit and, since 2002, has been allowed to use any “savings” that accumulate to make up for overages in other years. Key features of the new cap include:

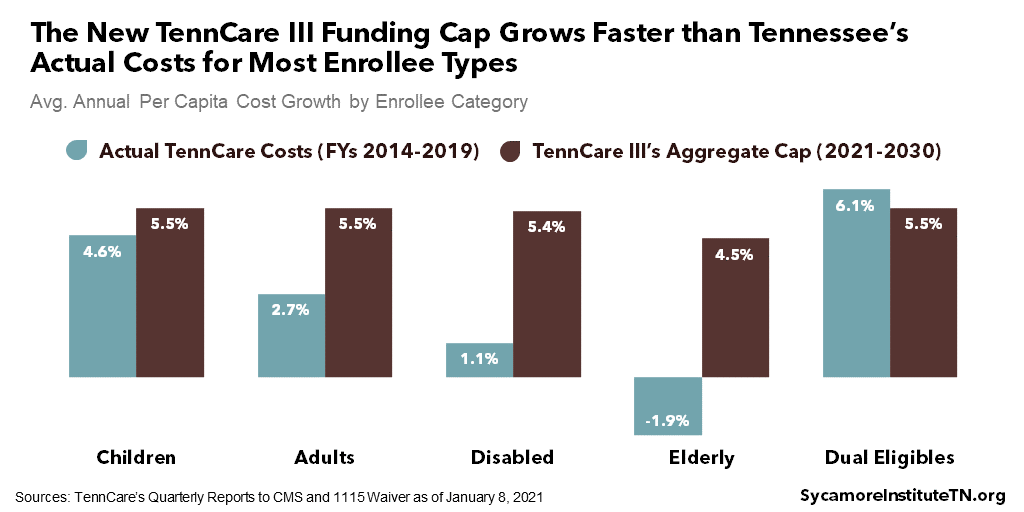

- Enrollee-Specific Per Capita Costs – The basis for the cap is Tennessee’s actual per capita costs for five enrollee categories in 2019 – children, adults, people with disabilities, individuals age 65+, and those enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (i.e. “dual-eligibles”). These costs have been inflated by the national rate of growth to establish a 2021 cap for each group.

- Enrollee-Specific Cost Projections – Each year, the per capita costs will grow by the national rate of growth projected in the president’s budget for each of the enrollee groups.

- Enrollment – The cap will rise or fall if enrollment in any of the five categories is 1% above or below its 2019 level. Compared to historical enrollment trends, the range in which the cap would remain unchanged is relatively narrow (Figure 1).

- No Exclusions – As with TennCare II’s existing budget neutrality cap, the new aggregate cap applies to all costs covered by the TennCare waiver. In the state’s proposal, supplemental payments to hospitals, prescription drug coverage, and dual-eligibles were not capped.

- Rebasing – The cap will reset in 2026 based on Tennessee’s actual per capita costs for each enrollee group in 2021-2024. Growth will continue to be pegged to the national projections in the president’s budget.

- Cap Compliance – Federal regulators will look at TennCare spending over the entire 10-year period to determine if the state exceeded its aggregate cap. This means that spending less than the cap in one year could offset overages in another. The state can also tap about $6 billion in savings “rolled over” from the last five years of the TennCare II waiver.

- Retroactive Eligibility – Moving forward, pregnant women and children who enroll in TennCare will be able to have medical expenses incurred prior to enrollment covered retroactively for up to three months.

Figure 1

[mk_custom_box bg_color=”#c2d7dc” padding_vertical=”20″ padding_horizental=”15″]

What Is a Medicaid Waiver?

TennCare has operated under an “1115 waiver” since 1994, which lets it deviate from some federal Medicaid rules. Federal regulators can issue these waivers to states so as long as the changes involved promote the objectives of the Medicaid program.

The typical steps for seeking and approving a waiver have accumulated over time in both policy and precedent. For example:

- After an initial public comment period, state and federal officials negotiate the terms of a waiver in a process that is often informal, not public, and without specific deadlines.

- Historically, waivers and renewals expire after no more than five years.

- Most waivers are very specific about how states can deviate from federal rules and require further approval for any changes not specified (e.g. adding a new optional benefit).

All Medicaid programs with 1115 waivers must meet “budget neutrality” rules. In other words, a state cannot cost the federal government more than it would without the waiver. There are two ways to set this budget neutrality cap, which acts as a limit on federal funding for all activities under the waiver. TennCare has traditionally used the per member per month (PMPM) approach based on expected monthly enrollee costs, expected spending growth, and actual enrollment. Meanwhile, the aggregate cap approach accounts for expected enrollee costs and spending growth but not changes in actual enrollment.

See Understanding Medicaid and TennCare: Key Concepts and Context to Know to learn more about how Medicaid works and Tennessee’s history with the program.

How the New Waiver Compares to TennCare II

Below, we explain six key differences between the TennCare III agreement and what a typical TennCare II renewal might have looked like. See Appendix Table 1 for a side-by-side comparison of the new TennCare III waiver, recent federal policy and precedent, and what Tennessee proposed in November 2019.

1. Tennessee may get more federal Medicaid dollars without spending any new state money.

If TennCare spends less than its new federal cap, the state could get up to 55% of the difference as “shared savings.” The agreement lets Tennessee use existing state spending on other health-related programs to match this money, which is not currently allowed. However, savings rolled over from the prior waiver do not count. This new source of federal funding would free up as much as 65% (i.e. the state’s regular FMAP) of the state dollars currently spent on the programs listed below. Only state spending on these programs would be eligible for a shared savings match, and any changes to this list would require federal approval.

- Charitable clinics funded by the Department of Health’s primary care safety net

- The Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services’ behavioral health safety net

- Safety net services funded by the Department of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- K-12 nurses, psychologists, social workers, and at-risk student services funded through the Department of Education

- CoverRx prescription drug assistance program for low-income Tennesseans

State dollars freed up in this way could pay for other expenses, seemingly without restriction. The agreement does not appear to restrict or require reporting on Tennessee’s use of newly available state funds. In a press release, TennCare pointed to its initial proposal and recent budget requests, which prioritized things like dental coverage for new and expecting mothers, expanded post-partum coverage, and waitlists for long-term services and supports. (5) Uses like these would draw down more federal Medicaid funds but would also count towards the state’s spending cap. In addition, Tennessee could use the freed-up state dollars in ways – either health-related or not – that are not eligible for a federal match. In all cases, the shared savings would represent a non-recurring source of funds and would have to be approved during the annual budget process.

The level of shared savings available to Tennessee will depend on its performance on quality measures. Tennessee could access 45% so long as it maintains its performance on a to-be-determined set of 10 quality measures. If the state shows improvement on the measures, it could earn up to 55% of shared savings. It is unclear if the process of choosing the measures will play out in public.

Tennessee will likely get far less shared savings under this agreement than the state initially requested (Figure 2). TennCare’s November 2019 proposal based its modified block grant on the caps established in prior waivers. Those caps relied on national costs and trends that, in the aggregate, were well above what Tennessee actually spends on Medicaid. The state had also proposed that the block grant increase when enrollment grows but hold steady when it drops. The final agreement takes a different approach – rebasing the caps and allowing for both increases and decreases due to enrollment.

Figure 2

2. TennCare can limit coverage of prescription drugs – a common practice for private insurers and Medicare but never before allowed in Medicaid.

Tennessee is the first state allowed to use a restricted drug formulary for Medicaid. For adult enrollees, TennCare can choose not to cover some prescription medications without losing mandated discounts from the drug industry. However, the state would have to allow exceptions when a non-covered drug is deemed medically necessary – a process that has not yet been established. Exemptions are also carved out for drugs to treat HIV/AIDS and opioid use disorder. While federal regulators have never before approved a restrictive formulary in Medicaid, Tennessee and many other states do require prior authorization for drugs that are not on their preferred lists. (6)

3. The state would not need further approval for any changes that keep TennCare eligibility and benefits at or above end-of-2020 levels.

Tennessee will no longer need prior federal permission to tap existing flexibilities to change features of the program. As long as TennCare meets the requirement discussed below, it can add new populations and benefits and change enrollment processes, delivery systems, uncompensated care payments to hospitals, and other elements at will. The state would also be able to roll back any such decisions it makes in the future. In addition, any new populations or benefits would be exempt from certain rules – like the requirement to offer identical benefits to every eligible resident of the state (i.e. “comparability” and “statewideness”).

Any reduction in eligibility or benefits below end-of-2020 levels and certain managed care changes would still need federal sign-off. This “maintenance of effort” requirement would trigger the traditional federal approval process for any changes that reduce eligibility or benefits relative to December 31, 2020. TennCare must also continue to meet all reporting and approval requirements associated with managed care oversight regulations.

Existing notification and transparency requirements still apply – whether or not the change in question needs federal approval. Both TennCare and the federal government will still need to publicize proposed changes and seek non-binding public comments before they can take effect – including those that do not need federal permission.

4. Due to changes in federal policy, TennCare III may pose less financial risk to Tennessee than a renewal of the existing program.

Since TennCare’s last renewal in 2016, federal Medicaid officials made a policy change seen as likely to create new financial risks for TennCare when it came up for renewal this year. (7) This new standard for waiver renewals calls for much stricter caps on federal funding to keep Medicaid spending at or below each state’s recent trend. See Appendix Table 1 for additional details on the new standards and how they compare to the TennCare III agreement.

As a result, TennCare III’s funding structure likely exposes Tennessee to less financial risk than it would otherwise face (Figure 2). Tennessee’s per capita Medicaid spending has grown slower than most other states’, so staying below a federal funding limit pegged to the state’s already low spending could have become much harder going forward (Figures 3 and 4). The state may face some additional risk under the waiver if enrollment grows less than 1% above 2019 levels, but overall, the terms are more advantageous. While it is technically possible that Tennessee might have negotiated to renew the existing waiver with a similarly advantageous cap, the odds of success are unclear.

Figure 3

Figure 4

5. The new shared savings provisions add to the state’s existing financial incentive to reduce TennCare spending.

The shared savings approach increases the ‘value’ to the state budget from spending less on TennCare. In FY 2019, TennCare took up about 21% of all state spending, so there is already a strong incentive to find efficiencies in the program. Under the new waiver, however, any reduction in TennCare spending (while still subject to maintenance of effort requirements) could free up about twice as much money in the state budget. Currently, reducing total TennCare spending by $3 saves roughly $1 for the state and $2 for the federal government. Going forward, however, the state would also keep about half of the federal savings – which could free up state dollars for other purposes (Figure 5).

The maintenance of effort requirement does limit Tennessee’s ability to reduce its Medicaid spending. TennCare could tap new and existing flexibilities to produce savings within the funding cap that could potentially affect things like utilization or payment models. However, any changes that explicitly reduce eligibility or benefits below December 2020 levels would require federal approval and trigger an adjustment to the state’s aggregate cap. There would be no additional financial incentive to reducing enrollment since the cap falls when enrollment falls by more than 1% below 2019.

Figure 5

6. If policymakers want to roll back TennCare III, it could take longer than prior waivers.

The TennCare III waiver does not have to be renegotiated until 2030. Although TennCare did not receive the permanent approval it requested, TennCare III represents only the second the time to date that the federal government has given a 10-year approval. Traditionally, waivers and waiver renewals have only been approved for 3-5 years at a time.

Separate federal guidance lays out a lengthy process for ending a state’s waiver early. Federal Medicaid regulators recently established a new process that gives states at least nine months before federal officials can terminate an approved waiver – during which time states have a window of opportunity to appeal. (9)

The Bottom Line

TennCare III’s funding structure and flexibilities create an unprecedented and complex set of new incentives and opportunities for state policymakers. The agreement’s advantageous federal funding limit mitigates any downside risk and could bring additional federal dollars to Tennessee even without other changes to the program. Meanwhile, state officials can also use new authorities and flexibilities to reduce program costs more easily – freeing up even more state dollars.

These flexibilities also create new uncertainties for people already using TennCare and any who may enroll later under the new waiver. For example, Medicaid stakeholders – particularly those with complex health care needs – have long been uneasy about maintaining timely access to the drugs they need under a formulary. Meanwhile, the flexibilities that allow TennCare to quickly add new populations and benefits also lets them roll back those changes faster. At the same time, there are new, more valuable incentives to find savings within TennCare and few limits on how the state can use the money that might free up. Even with the maintenance of effort requirement, the resulting uncertainties will likely make people who rely on the program for health care anxious.

TennCare III does not address or preclude a comprehensive expansion of eligibility to all adults with incomes under 138% of poverty if state policymakers choose to pursue that. Under the new agreement, TennCare can expand eligibility to new groups without prior federal approval – including those eligible under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). However, the new waiver is unlikely to generate enough savings to fund Tennessee’s 10% share of costs for a full ACA eligibility expansion. Tennessee would also have to go through the regular approval process to access the 90% federal match for that population. Nothing in the TennCare III waiver precludes that, but state and federal officials would have to negotiate if and how it would affect the new funding cap, shared savings, and other items in the waiver. State lawmakers would also have to authorize this type of expansion.

TennCare’s recent record of instituting significant changes has had mixed results. In some circumstances, TennCare has been cited as a national leader in innovative payment and benefit models (e.g. value-based purchasing for behavioral health). (10) (11) (12) (13) In other cases, it has been criticized for how it has handled the implementation of major administrative changes (e.g. eligibility redetermination) and the monitoring of new initiatives (e.g. episodes of care). (14) (15) (16) (17)

What Could Come Next

The TennCare III agreement requires approval from state lawmakers before it takes effect. The same legislation that required the Lee administration to submit its initial block grant proposal to the federal government also requires the General Assembly’s approval of the final plan. (18)

Any major changes to the program associated with the new features of TennCare III will take time to materialize. Many of the flexibilities require public input and prior notification to the federal government. It will also take TennCare some time to create a new formulary and the processes associated with it. Meanwhile, shared savings do not have to be used in the year they are earned. It could take several years to accumulate enough savings to launch any of the program priorities TennCare officials have identified.

The Biden administration could rescind the approval, but the Trump administration has taken steps to lengthen that process. There is tremendous pressure from Medicaid stakeholders nationwide to overturn many of the new approaches floated by the Trump administration (e.g. work requirements, block grants). (19) (20) (21) By extending the waiver period and sending out new waiver termination guidance, however, the current administration may have slowed down the next one’s ability to roll back the TennCare III waiver.

At the same time, this agreement will almost certainly face legal challenges in state and federal court. The TennCare III waiver includes legal justifications for many of its more novel and contentious elements – including shared savings and the drug formulary. Those arguments, however, may not prevent lawsuits from being filed against the federal government. Meanwhile, any changes down the road that may negatively affect a TennCare enrollee could trigger a lawsuit against the state. As to the specific circumstances, legal arguments involved, and chance that ongoing legal proceedings halt the waiver’s implementation – only time will tell.

References

Click to Open/Close

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and TennCare. TennCare III: Tennessee’s 1115 Demonstration Waiver. [Online] January 8, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/tenncarewaiver.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee Medicaid Block Grant Waiver Amendment Approved by Federal Government. [Online] January 8, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/governor/news/2021/1/8/tennessee-medicaid-block-grant-waiver-amendment-approved-by-federal-government.html.

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS Administrator Seema Verma’s Press Call Remarks as Prepared for Delivery on TennCare. [Online] January 8, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-administrator-seema-vermas-press-call-remarks-prepared-delivery-tenncare.

- TennCare. Enrollment Data. [Online] [Cited: January 11, 2021.] https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/information-statistics/enrollment-data.html.

- —. Tennessee Medicaid Block Grant Waiver Agreement: Frequently Asked Questions. [Online] January 8, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/TennCareBlockGrantFAQs.pdf.

- OptumRx. TennCare Preferred Drug List: Effective January 1, 2021. [Online] [Cited: January 12, 2021.] https://www.optumrx.com/content/dam/openenrollment/pdfs/Tenncare/home-page/preferred-drug-list/Preferred%20Drug%20List%20(PDL).pdf.

- Hill, Timothy B. SMD # 18-009: Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Waivers. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Online] August 22, 2018.

- TennCare. Quarterly Reports to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). [Online] 2013-2019. [Cited: January 12, 2020.] Available from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/demonstration-and-waiver-list/83206.

- Stein, Michelle. Verma Saddles Biden CMS With New Procedures For Axing 1115 Demos . Inside Health Policy. [Online] January 8, 2021. (Subscription Required) https://insidehealthpolicy.com/daily-news/verma-saddles-biden-cms-new-procedures-axing-1115-demos.

- Soper, Michelle Herman, Matulis, Rachael and Menschner, Christopher. Moving Toward Value-Based Payment for Medicaid Behavioral Health Services. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. [Online] June 2017. https://www.chcs.org/media/VBP-BH-Brief-061917.pdf.

- Smith, Derica and Hanlon, Carrie. Case Study: Tennessee’s Perinatal Episode of Care Payment Strategy Promotes Improved Birth Outcomes. National Academy for State Health Policy and the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality. [Online] October 2017. https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Tennessee-Case-Study.pdf.

- Spencer, Anna and Crawford, Maia. Promising State Innovation Model Approaches for High-Priority Medicaid Populations: Three State Case Studies. Center fo Health Care Strategies, Inc. [Online] March 2019. https://www.chcs.org/media/Promising-State-Innovation-Model-Approaches.pdf.

- Honsberger, Kate and Hanlon, Carrie. Tennessee: Using Managed Care Incentives to Improve Preventive Services and Care for Children. National Academy for State Health Policy. [Online] January 2018. https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Tennessee-Case-Study-2018.pdf.

- Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. Review of TennCare Eligibility Redeteriminations. [Online] December 6, 2017. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/sa/advanced-search/2017/tenncarememoandreport.pdf.

- —. Performance Audit Report: Division of TennCare. [Online] December 2018. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/sa/advanced-search/2018/pa18043.pdf.

- Kelman, Brett. Tennessee Erased Insurance For At Least 128,000 Kids. Many Parents Don’t Know. The Tennessean. [Online] April 1, 2019. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/health/2019/04/02/tennessee-tenncare-coverkids-medicaid-erased-health-care-coverage-for-children/3245116002/.

- Kelman, Brett and Reicher, Mike. At Least 220,000 Tennessee Kids Faced Loss of Health Insurance Due to Lacking Paperwork. The Tennessean. [Online] July 14, 2019. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/investigations/2019/07/14/tenncare-coverkids-medicaid-children-application-insurance-denied/1387769001/.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 481 (2019). [Online] May 24, 2019. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/111/pub/pc0481.pdf.

- Huberfeld, Nicole and Shafer, Paul. In Its First 100 Days, The Biden Administration Must Restore The Soul Of Medicaid . Health Affairs. [Online] January 11, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20210106.54888/full/.

- Rosenbaum, Sara. How the Biden Administration Can Act to Strengthen Medicaid. Commonwealth Fund. [Online] December 11, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/how-biden-administration-can-act-strengthen-medicaid.

- Alker, Joan. What Can We Expect from Biden Administration on Work Reporting Requirement Waivers? Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. [Online] November 12, 2020. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2020/11/12/what-can-we-expect-from-biden-administration-on-work-requirement-waivers/.

- Hill, Timothy B. SMD # 18-009: Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Waivers. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Online] August 22, 2018. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18009.pdf.

- Lynch, Calder. SMD # 20-001: Healthy Adult Opportunity. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). [Online] January 30, 2020. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd20001.pdf.

- TennCare. Amendment 42: Modified Block Grant and Accountability. [Online] November 20, 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/Amendment42FinalVersion.pdf.