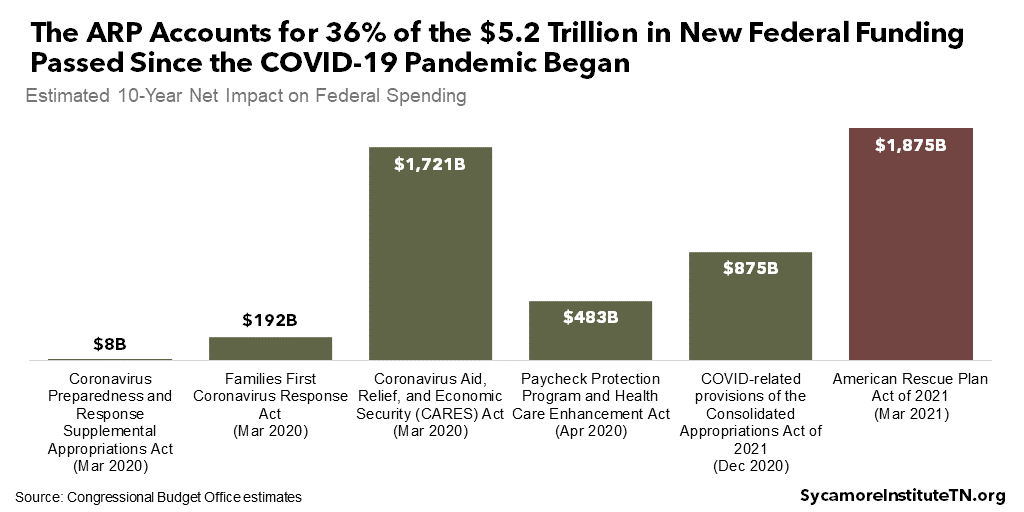

The American Rescue Plan is the largest of six federal funding packages passed since the COVID-19 pandemic began last year (Figure 1). (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) The first five are already bringing at least $9 billion to Tennessee state government, and tens of billions more have gone to residents, businesses, and communities across the state. This latest package will bring another large wave of federal funding that state and local policymakers can use over the next three to four years to address short- and/or long-term challenges.

This report summarizes new federal aid available to Tennessee under the American Rescue Plan (ARP), including the amounts, allowable uses, and what it means for households, businesses, and state and local governments.

Key Takeaways

- The American Rescue Plan could bring $20-30 billion into Tennessee on top of about $35 billion already committed by five other federal funding packages approved since March 2020.

- This unprecedented influx of one-time federal money poses opportunities and challenges for state policymakers to control the pandemic, repair its economic damage, and make long-term investments.

- Some of the more significant areas of funding include:

- Flexible aid to state and local governments.

- Extensions of many existing unemployment compensation policies from previous COVID relief packages.

- Recovery payments directly to individuals.

- One-year expansion of a number of tax credits for families and low-income workers.

- More resources for COVID-19 testing, vaccines, and emergency response.

- Additional subsidies and funding to expand access to health insurance coverage.

- Targeted relief for a number of public and private sector industries the pandemic has hit especially hard.

- Funding for dozens of housing and social service programs related to various economic effects of the pandemic.

Figure 1

Overview of the American Rescue Plan

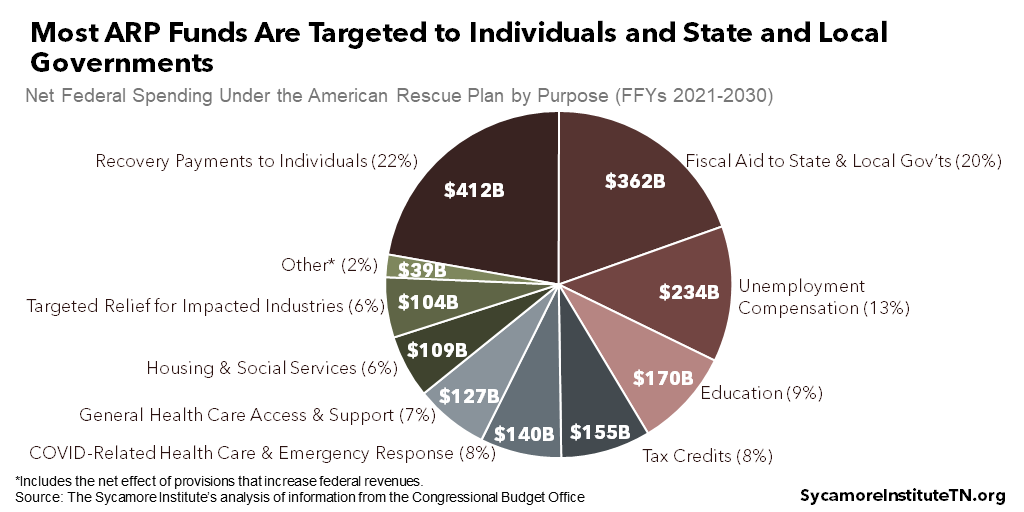

The ARP increases federal spending by an estimated $1.9 trillion to fund dozens of programs across hundreds of provisions. Many key pieces of the package repeat, extend, or expand programs and services first included in past coronavirus relief packages. The majority of the ARP money is targeted to individuals and state and local governments (Figure 2):

- Recovery Payments to Individuals – $412 billion (22%) for another round of direct payments to individuals.

- Fiscal Aid to State & Local Governments – $362 billion (20%) in flexible fiscal aid to both state and local governments.

- Unemployment Compensation – $234 billion (13%) to extend prior COVID-related unemployment compensation

- Education – $170 billion (9%) for K-12 and higher education.

- Tax Credits – $155 billion (8%) for tax credits to individuals and businesses for things like child care and paid leave.

- COVID-19 Response – $140 billion (8%) for testing, vaccinations, and emergency response directly related to COVID-19.

- Other Health Care – $127 billion (7%) in support for health care providers and expanded access to health care and coverage.

- Social Services – $109 billion (6%) for housing and social services like the supplemental nutrition assistance program and rental assistance.

- Targeted Industry Relief – $104 billion (6%) in targeted relief for impacted industries like restaurants, venues, transit, and air travel.

The new law could bring $20-30 billion into Tennessee on top of about $35 billion already committed by prior funding packages. (6) (5) The sections that follow summarize and provide additional context for some of the larger investments the state can expect to see and what they could mean for residents, businesses, and communities.

Figure 2

Figure 3

The Big Picture

This unprecedented influx of one-time federal money poses opportunities and challenges for Tennessee policymakers to control the pandemic, repair its economic damage, and make long-term investments.

Control the Pandemic

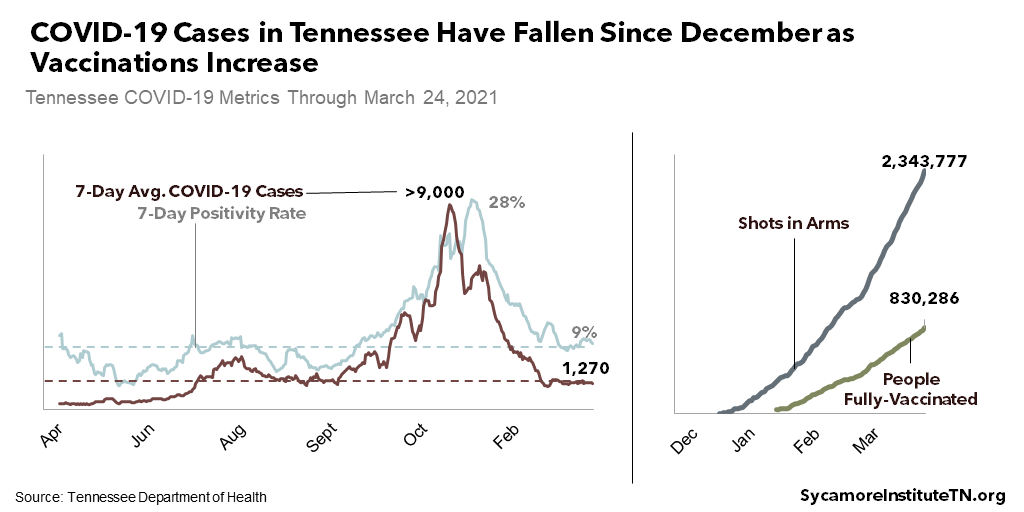

Reducing the spread of COVID-19 remains the single most important thing policymakers can do to expedite a full economic recovery. Consumer spending data show concern about the virus’ spread likely did more than anything else to reduce demand last spring and summer, especially in the hard hit leisure and hospitality sector (e.g. restaurants, bars, performance venues, tourist attractions). Overall, COVID vaccinations in Tennessee are increasing, and case numbers have fallen back to the levels of last summer and early fall (Figure 3). The ARP gives states substantial funding to help those trends continue – including sustained money for testing, contact tracing, vaccinations, and a host of mitigation strategies as businesses and schools continue to reopen.

Repair Its Economic Damage

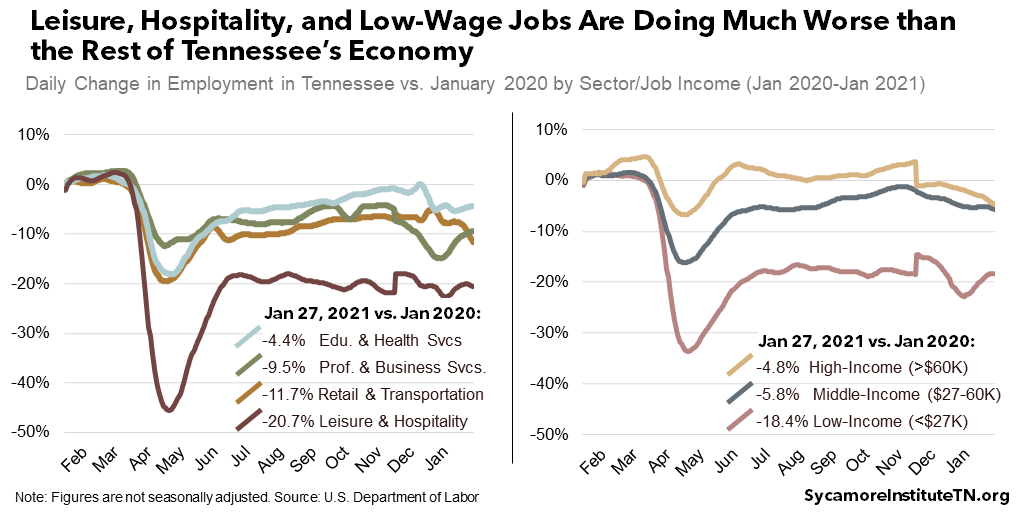

For the hardest-hit Tennesseans still in need of relief, new federal funding could provide a bridge to the post-pandemic economy. Many measures of Tennessee’s economy and fiscal health give cause for optimism, but leisure, hospitality, and low-wage jobs remain about 20% below pre-pandemic levels (Figure 4). Small businesses and lower-income households may have an especially hard time recovering. The longer demand remains low, the greater the chance for long-term economic damage from business closures and job losses without additional support.

Figure 4

Make Long-Term Investments

Much of this funding is flexible enough that policymakers could spend it on a range of long-term challenges that affect health and prosperity in Tennessee. Prioritizing these more forward-looking issues could help to put the state in a stronger position for the future.

Tennessee could use this money to assess its public health response to the pandemic and better prepare for future challenges. Some state policymakers are already considering changes to the organization of Tennessee’s public health system in light of COVID-19 experiences. The ARP could provide extra resources to take a comprehensive look at the state’s public health infrastructure to identify lessons learned, strengths, weaknesses, and potential improvements.

ARP resources could also support overdue investments in infrastructure and technology. For example, data and tech improvements could help policymakers better track, manage, and ensure access to the various programs and systems affected by the pandemic (e.g. telehealth for TennCare enrollees, electronic health records for incarcerated individuals, court and correction systems data). State, local, and school district grants can also be used for certain types of physical infrastructure. In the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Affairs’ (TACIR) inventory of infrastructure needs for 2019-2023, state and local officials identified projects – some already funded and underway – totaling (9):

- $5.2 billion for public school renovations.

- $5.0 billion for water and wastewater systems.

- $13.5 million for broadband internet.

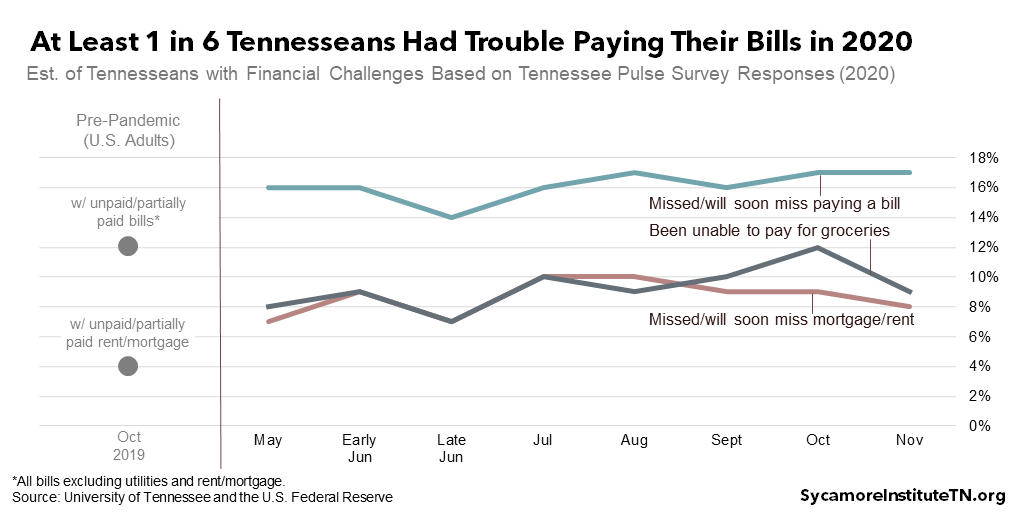

In addition, policymakers could fund pilot projects that inform efforts to help Tennesseans improve their health and economic resilience. As a state, we have high rates of many chronic conditions and health behaviors that increase the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 – like smoking, obesity, heart and kidney disease, and Type 2 diabetes. (10) In the last year, many Tennesseans also struggled to pay their housing, food, and other bills – with missed payments reported at higher rates than national pre-pandemic numbers (Figure 5). (11) (12) These residents’ health and financial challenges will have repercussions for themselves and our broader economy. Using ARP funds, policymakers could test innovative ways to help people achieve better health outcomes and greater economic security.

Figure 5

Challenges Facing State and Local Officials

State and local recipients of new federal aid will face challenges as they plan how and when to spend this influx of money. Some of the issues and considerations include:

- Finite Funding – ARP funds are one-time money that – in some cases – policymakers can spend over several years. Officials will have to figure out ways to deploy these finite resources in ways that help them achieve their recovery goals without creating future unfunded obligations.

- Overlap and Duplication – State, county, and municipal fiscal aid funds can all be used for the same set of purposes. Meanwhile, several federal funding sources overlap in their coverage of COVID-19-related expenses (e.g. FEMA reimbursement, state and local fiscal aid, K-12 education relief, testing and vaccine funding). To make the most impact with the greatest efficiency and least duplication, different levels of government will need to carefully plan and coordinate together. This may prove quite challenging given the number of local governments involved (95 counties and 340 municipalities) – as well as the various rules and complexities of all the relevant federal agencies.

- Administrative Challenges – Depending on policymakers’ goals, some approaches could raise more administrative challenges and burdens than others – especially since state governments cannot use this money to offset tax cuts. For example, creating new programs instead of using existing services, grant opportunities, or the tax code could require needs assessments, applications, and other processes that impede the timely distribution of funds. Officials may also want to reserve some funds to cover the costs of accounting for and evaluating the effectiveness of their spending.

- Meeting Federal Requirements – The complexities involved with adhering to various federal rules could create challenges at all levels of government. For example, evolving guidelines can make it hard for state and local officials to plan. The Coronavirus Relief Fund (an earlier round of flexible funding to states) initially covered relevant expenses incurred before December 31, 2020. Federal regulators then updated the eligibility requirements multiple times – most recently in late November.(13) (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) (19) Finally, just three days before the funds were set to expire, Congress made them available for an additional year.

The new federal funding will almost certainly affect the state’s FY 2022 budget process. The American Rescue Plan provides money for many of the same state-funded initiatives proposed by Governor Lee – including for broadband and other infrastructure, technology improvements, and learning loss initiatives. As a result, we may see changes to the governor’s budget recommendation as the legislature works on it in the coming weeks.

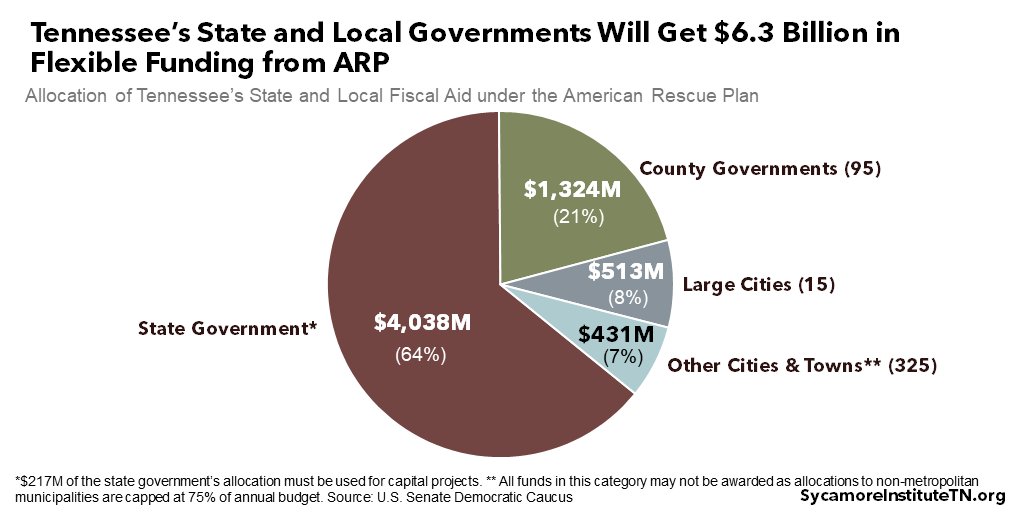

Figure 6

Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments

Tennessee is slated to receive a total of $6.3 billion from the ARP in flexible funding for state and local governments (Figure 6). (20) Under a prior round of flexible funding from the Coronavirus Relief Fund, a total of $2.6 billion was distributed only to state government ($2.4 billion) and the state’s three largest local governments ($285 million total).

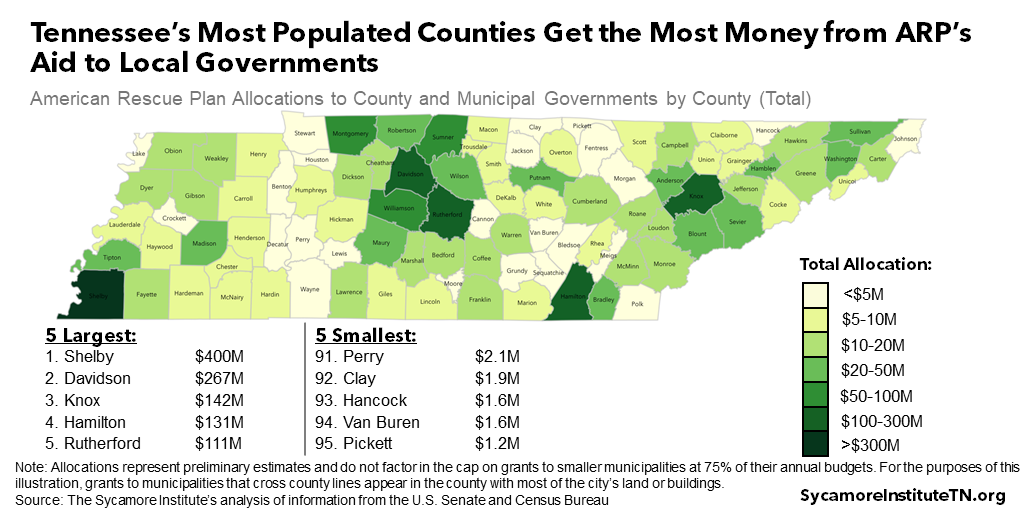

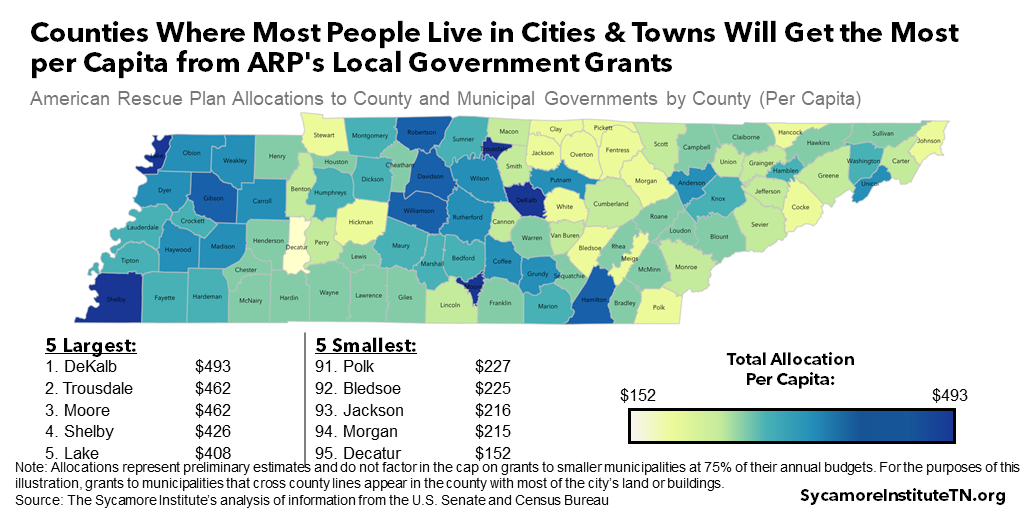

Local government allocations are based on either population or an existing federal funding formula. The Coronavirus Relief Fund created last year gave direct funding to just three local governments in Tennessee – Metro Nashville-Davidson County, Memphis, and Shelby County. ARP, on the other hand, will send money to every county government in the state and most municipalities. The most populated counties will get the largest allocations (Figure 7), while counties with a high share of residents served by municipal or metropolitan governments will get the most per capita (Figures 8) (20):

- County Governments – 95 grants ranging from $98,000 for Pickett County to $182 million for Shelby based on population.

- Metropolitan Cities – 15 grants ranging from $5 million for Bristol in Sullivan County to $168 million for Memphis in Shelby County based on a formula that accounts for population, poverty, and housing.[i]

- Other Cities and Towns – 325 grants ranging from $23,000 for Cottage Grove in Henry County to $16 million for Bartlett in Shelby County based on population. These grants will be administered by the state and capped at 75% of each municipality’s most recent annual budget. As a result, some of these funds may be returned to the federal government.(22) For example, the $24,000 estimated grant for Saulsbury in Hardeman County exceeds the cap since the town had about $27,000 in revenue and $20,000 in expenses in FY 2020. (23)

Figure 7

Figure 8

State and local officials will have wide discretion in how they spend this money over the next four years. The state allocation includes $217 million to use without a time limit on capital projects that “enable work, education, and health monitoring in response to COVID-19.” (24) (25) State and local governments must use all other ARP grant money on expenses incurred before December 31, 2024 on the following (22) (24):

- Costs directly related to COVID’s health and economic effects, including assistance to affected households, relief for small businesses and industries hurt by the pandemic, and aid to nonprofits.

- Premium pay for essential government employees.

- Investments in broadband, water, or sewer infrastructure.

- Offsetting a drop in tax revenue from one fiscal year to the next.(22)

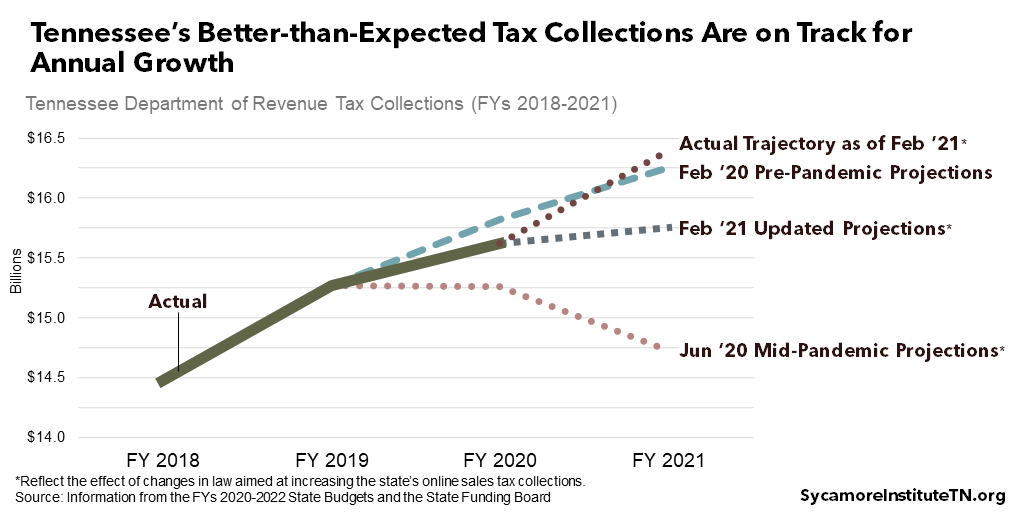

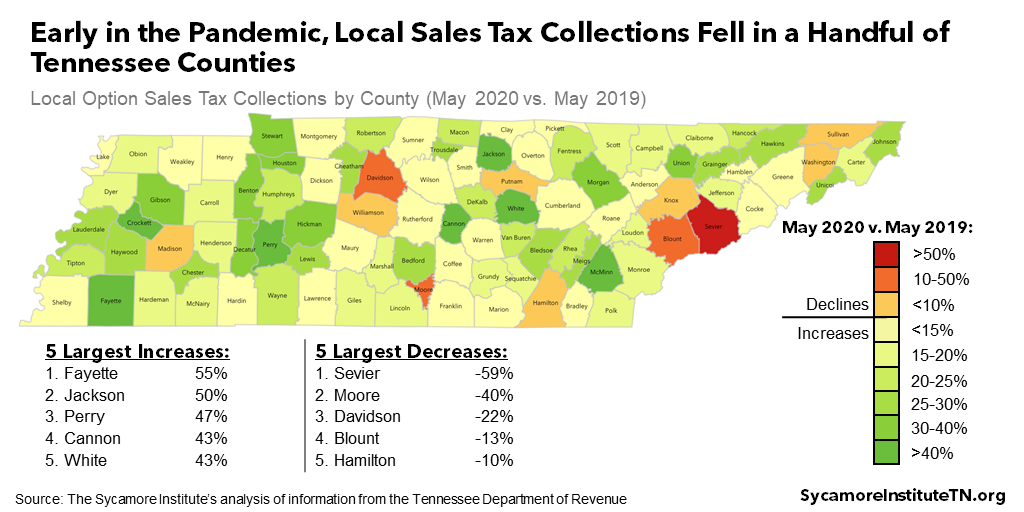

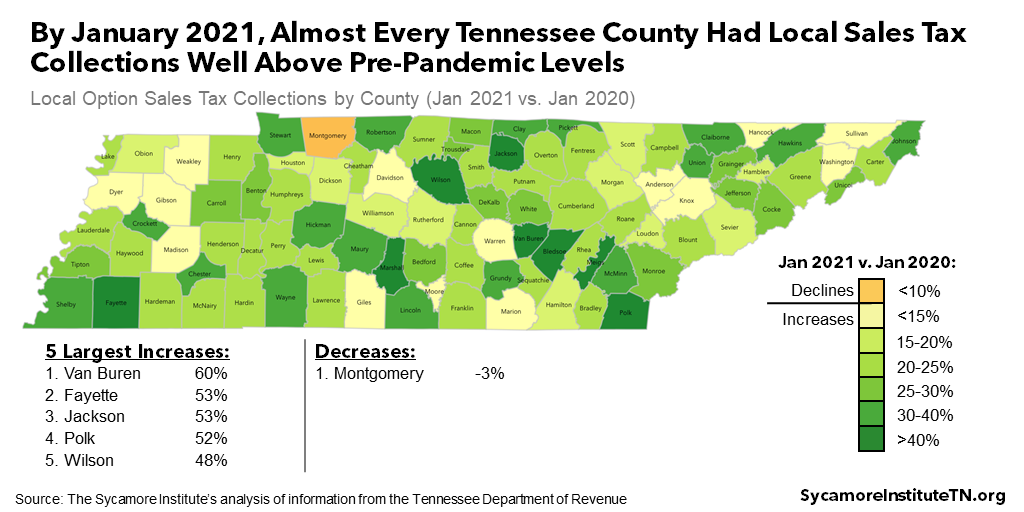

Tennessee state government and many localities may not meet the criteria for using these funds to replace lost revenue. Despite dire projections early in the pandemic, Tennessee’s total tax collections continue to grow (Figure 9). While a handful of counties saw local sales tax collections fall early on (Figure 10), nearly all were well above pre-pandemic levels by January 2021 (Figure 11). (26) The Biden administration may provide additional guidance on how to define revenue losses for this purpose (e.g. in total or by specific tax? adjusted for inflation? independent of tax changes that might have increased revenues over the prior years?).

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Comparing Tennessee’s revenue situation to other states’ is challenging. Real-time data for all 50 states are largely unavailable. There are also many ways to assess each state’s fiscal situation. For example, reporting and other analyses have attempted to compare revenues to prior years, to pre-pandemic projections, to post-pandemic projections, and to budgeted revenues. Overall, it appears that states’ fiscal situations are a mixed bag. For example:

- Across all 50 states last fall, expectations for general fund revenues were down 10.8% from pre-pandemic forecasts for FY 2021 and 4.4% for FY 2020. However, 18 states reported that FY 2021 revenues were coming in better than expected.(30)

- Adjusting for inflation, FY 2020 tax collections fell in 43 states compared to the prior year. Tennessee had one of the smallest declines.(31)

- Tennessee is among 23 states whose tax collections for March 2020-January 2021 were larger than what was collected in the year prior.(32)

State government cannot use ARP money to offset new tax cuts or to fund pensions. States cannot use the funds to offset the loss of revenues from any change made between March 3, 2021 and September 30, 2023 – legal or administrative – that cuts state taxes. This includes tax rate reductions, rebates, deductions, and credits. (22)

Figure 12

Unemployment Compensation

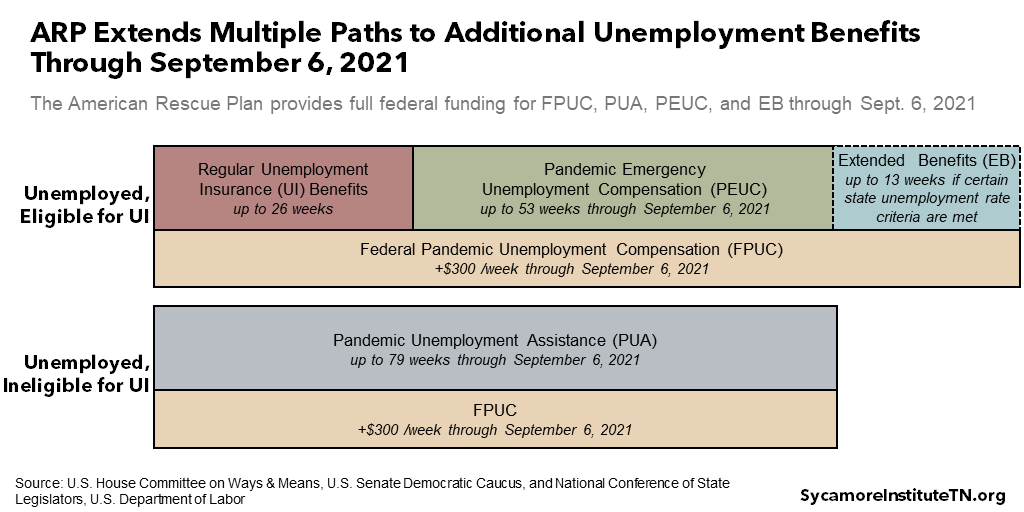

The American Rescue Plan extends many existing unemployment insurance (UI) policies from previous COVID relief packages. It includes federal funding through September 6, 2021 for the following provisions – many of which were set to expire on March 14, 2021 (unless otherwise noted) (Figure 12) (33) (34) (24) (35) (36) (37) (38):

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) – An additional $300 per week for those receiving UI. Congress reauthorized FPUC at this level in late December 2020 after initially providing an additional $600 per week from April-July 2020.

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) – $300 per week for up to 79 weeks for unemployed workers who aren’t normally eligible for UI (e.g. self-employed, part-time workers). The CARES Act made PUA available for up to 39 weeks, and the December 2020 relief package extended it to 50 weeks.

- Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) – Up to 53 additional weeks of UI benefits for those who exhaust their 26 weeks of regular UI. The CARES Act funded PEUC for up to 13 weeks, which was increased to 24 weeks in December 2020.

- Extended Benefits (EB) – Money to cover states’ 50% share of up to 13 weeks of extended benefits if workers exhaust their 26 weeks of regular UI while unemployment in their state is unusually high.

- Waiting Week – Fully reimburses states for waiving the 1-week waiting period for UI recipients retroactively to the beginning of 2021. Prior federal aid included 100% reimbursement through the end of 2020, when the amount dropped to 50%.

- Benefit Tax Exclusion – Excludes up to $10,200 of unemployment benefits from federal taxable income for households earning less than $150,000.

Figure 13

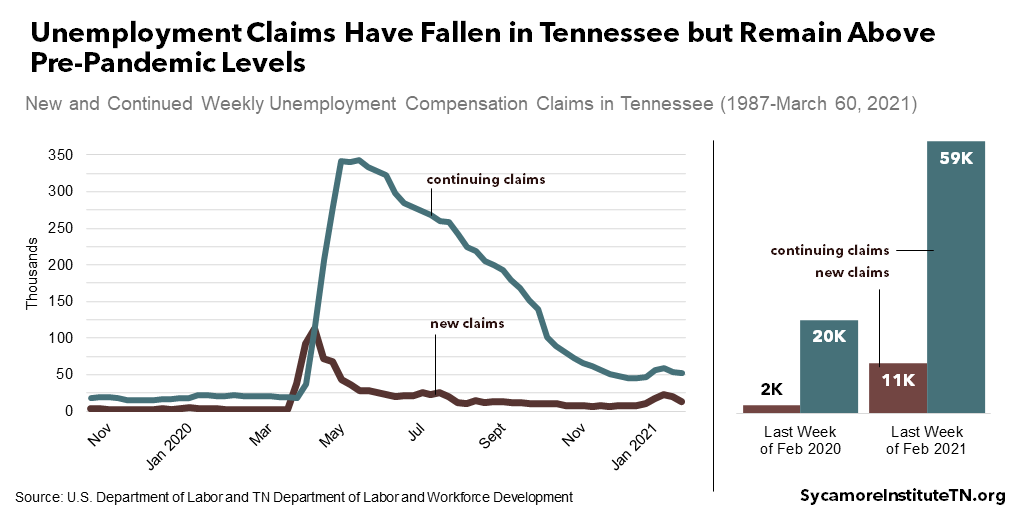

The number of unemployed Tennesseans on UI is still higher than before the pandemic began (Figure 13). After spiking to historically high levels in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, new and continuing claims began to fall. At the end of February, however, continuing claims remained nearly twice the level of one year earlier. New claims were nearly five times higher. (39) (40)

Direct Recovery Payments

The ARP includes a third round of direct relief payments to individuals of up to $1,400 for each adult and dependent. (34) (24) Payment amounts will phase down to zero for individuals making $75,000-$80,000 based on their 2019 or 2020 tax returns. About 3.2 million Tennessee households will get an estimated $8.2 billion. (41) The first round of direct relief paid up to $1,200 per adult and $500 per child. (42) The second was up to $600 per person and child. (43)

Tax Credits for Families and Low-Income Workers

The latest relief package expands a number of tax credits for families and low-income workers for 2021. These include (35):

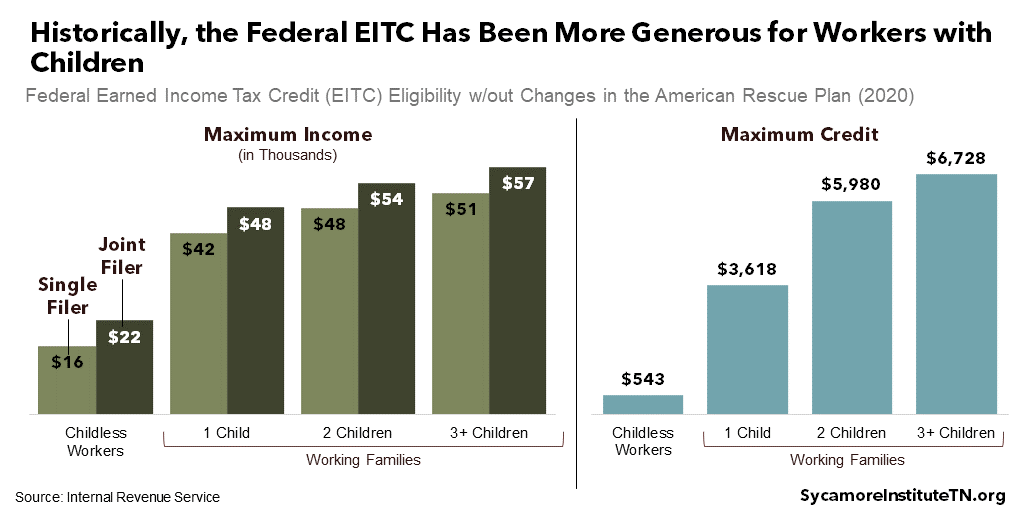

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) – Increases and expands the EITC for low-income working adults without children. In 2021, the maximum credit will increase from $543 to $1,502. It also and expands eligibility to include adults ages 19-24 and over 65, as well as those with incomes slightly above the current $16,000 maximum. In 2020, about 604,000 Tennessee households claimed about $2,550 each from the EITC, on average.(44) An estimated 395,000 additional Tennesseans will qualify for the EITC under this provision. (45)

As a refundable tax credit on a portion of workers’ incomes, the EITC effectively raises the earnings of eligible low- and moderate-income adults. Researchers generally agree that the EITC incentivizes work and reduces poverty, but the income limits and credit size have traditionally been less generous for childless workers (Figure 14). (46)

- Child Tax Credit – Increases the federal tax credit for dependent children from $2,000 per child to $3,000-$3,600 depending on the child’s age and boosts the maximum child age from 16 to 17. By making the credit fully refundable, it also allows individuals with little or no income tax liability to receive a tax refund of up to the maximum credit amount. Eligible families can also opt to get up to half of their credit in monthly installments. Some have likened the expansion to “child allowance” policies which vary in detail but generally include regular payments to families with children.

- Child Care Tax Credit – Boosts the maximum tax credit available for child care expenses from $1,050 for one child and $2,100 for two or more to $4,000 and $8,000, respectively, and makes the credit fully refundable.

Figure 14

Figure 15

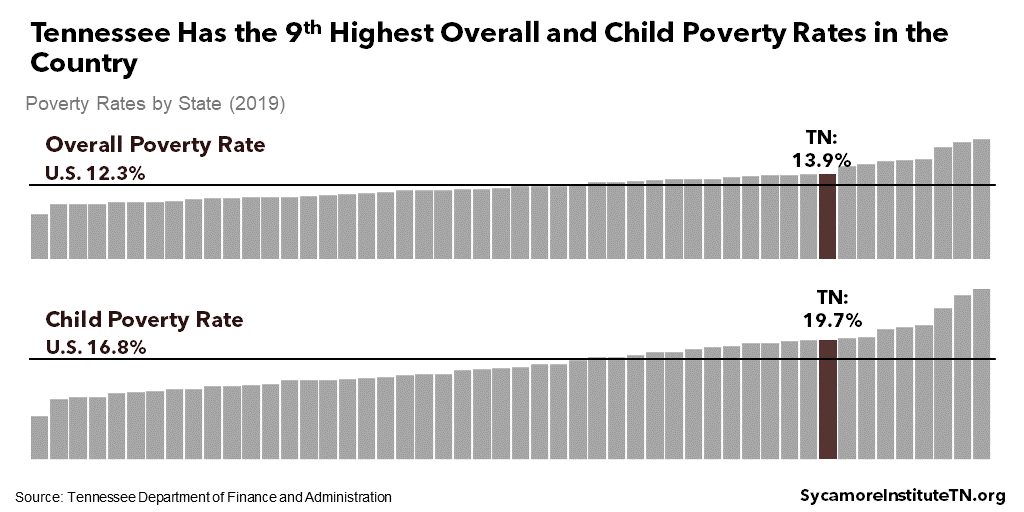

These provisions are expected to reduce Tennessee’s high rates of poverty. In 2019, 13.9% of all state residents and 19.7% of all children lived in households with incomes under the poverty – the 9th highest rates in the country (Figure 15). (48) Refundable tax credits like the EITC and other public assistance (e.g. UI, temporary assistance for needy families) already reduce Tennessee’s official poverty rate by an estimated 10% every year. (49) Available estimates forecast that the expansion of the tax credits above could further reduce Tennessee’s child poverty rate by between 30%-45%. (50) (45)

Each of these tax credits come with potential trade-offs. For example, the EITC has an unusually high rate of improper payments to people who are not actually eligible, which some attribute to its complex eligibility criteria. (51) (52) There is also concern that these credits can create undesirable or suboptimal incentives. The child tax credit, for example, is not linked to employment and so may discourage work. (53) Both credits could also better incentivize married households. And while the EITC encourages recipients to enter the workforce, it does not have the same effect on second earners in a family or encourage working more hours. (54) (55)

Education

The American Rescue Plan repeats and increases education funding from prior relief packages. Tennessee’s is expected to receive a total of $3.3 billion, including (56):

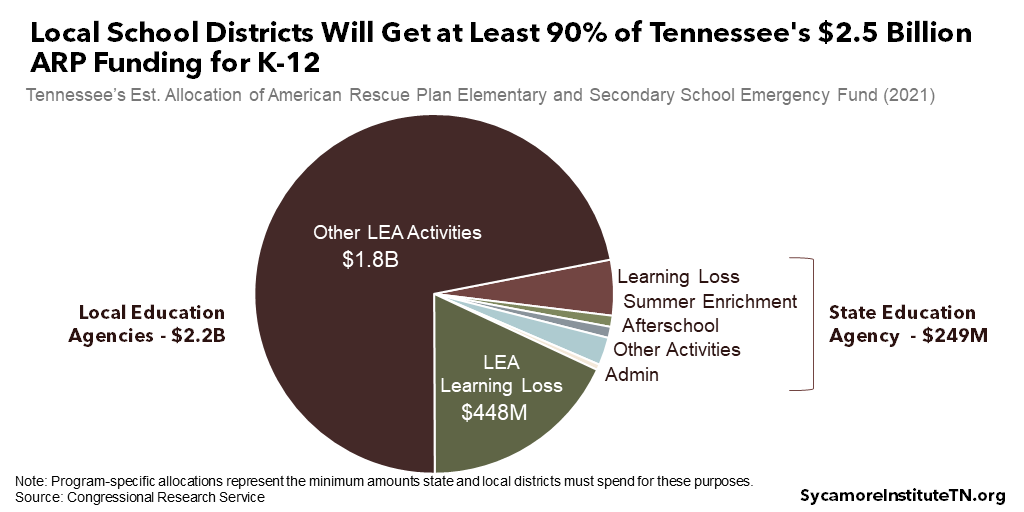

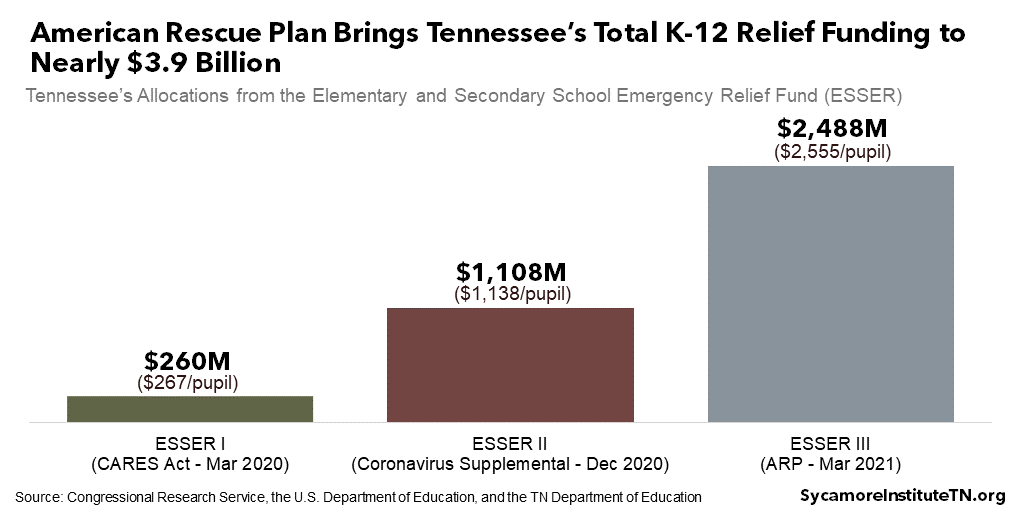

- K-12 Public Education – $2.5 billion from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER). (56) At least 90% of the funds will be distributed to local school districts, which must spend at least 20% to address learning losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 16). Outside of specific set-asides for learning loss and other activities, school districts have very broad flexibility in how they spend the funds. The U.S. Department of Education must spend the funds by September 30, 2023, and they may issue specific timelines for state and local expenditures. (34)(22)

This will be the state’s third and largest ESSER allocation. Tennessee has already received $1.4 billion from last year’s COVID-19 relief packages (Figure 17). (57) (58) Those prior allocations must be spent by June 30, 2022 and June 30, 2023, respectively. Most of that money remains unspent, as school district applications and spending plans for the most recent round of K-12 relief were not due until March 15, 2021. (59)

- K-12 Private Education – $80 million to provide assistance to private schools affected by the pandemic.

- Higher Education – $702 million to public and private post-secondary schools, which must spend at least half on emergency financial aid grants to students. The remainder can be used to offset lost revenues and emergency expenses related to COVID-19. Funds must be spent by September 30, 2023.

Figure 16

Figure 17

COVID-19 Testing, Vaccines, and Emergency Relief

The American Rescue Plan puts more money in FEMA’s disaster relief fund, which reimburses state and local governments for COVID-19-related costs. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimburses state and local governments and nonprofits for certain expenses related to presidentially-declared disasters. As of January 2021, Tennessee was eligible for over $700 million in FEMA disaster relief reimbursement for COVID-related expenses and is expected to get another $500 million through September 30, 2021. (61) The ARP’s $50 billion for the disaster relief fund is expected to pay for these costs through the end of FY 2021. (61)

Recently, the Biden administration substantially expanded the scope of FEMA reimbursement for COVID-19-related measures. Under the new policy, FEMA will pay 100% of all eligible costs back to January 2020 instead of 75%. The list of eligible expenses also grew to include costs associated with opening schools, childcare facilities, transit systems, etc. Expenses that were already eligible include personal protective equipment, testing, operating food banks and alternate care sites, and disinfecting public facilities. (62)

The ARP also provides targeted funding for COVID-19 testing and vaccines. A total of $48 billion will go toward COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, and other mitigation efforts. Another $8 billion will support vaccine distribution. It is not yet clear how much of this money states will get. (33) (34)

Access to Health Care

The ARP increases and expands subsidies in 2021 and 2022 for people who buy eligible health insurance plans at healthcare.gov. People with incomes between 100-400% of poverty will get additional premium assistance, and premiums will be capped at 8.5% of income for those earning between 400-500% of poverty. (63) About 218,000 Tennesseans enrolled in individual market coverage via healthcare.gov for 2021. (64) (65) In 2020, 86% of Tennessee’s enrollees qualified for premium subsidies. (66)

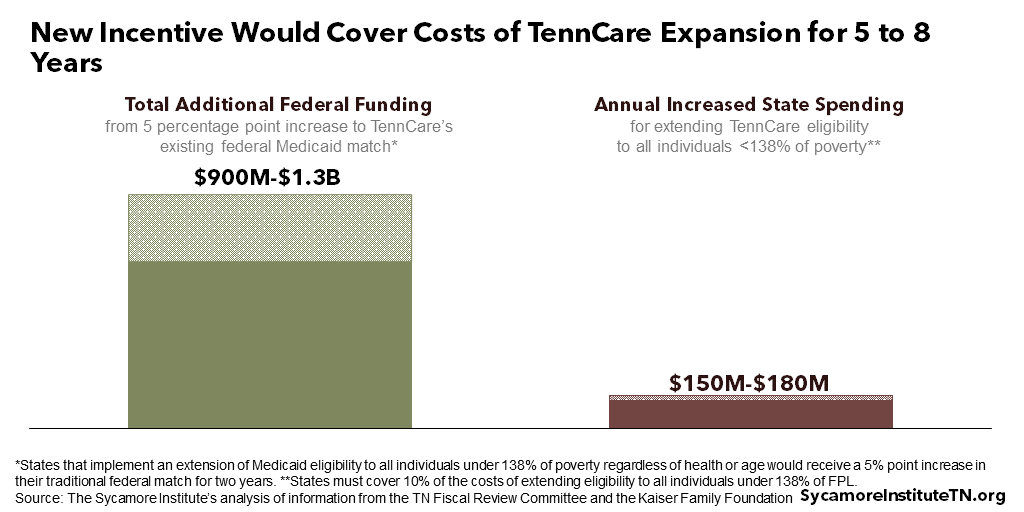

The new law also offers a two-year increase in federal funding to states that extend Medicaid eligibility to all residents with incomes below 138% of poverty. Today, thirty-eight states cover everyone under that threshold regardless of their health or age. Tennessee is one of 12 states where residents must first match an eligible category (e.g. child, pregnant woman, person with a disability), each of which has its own income requirements. (64) In exchange for expanding eligibility, these 12 states would get a two-year, five percentage point bonus to their standard federal Medicaid match for existing enrollees.

In Tennessee, this incentive would cover the state’s costs of expanding Medicaid eligibility for an estimated 5-8 years (Figure 18). To collect the incentive, TennCare would need to extend eligibility to an estimated 230,000 uninsured Tennesseans with incomes under 138% of poverty. (70) (71) If state policymakers take that step, the federal government would pay about 70% of existing TennCare costs for two years – up from the usual rate of about 65%. Tennessee would get between $900 million[i] and $1.3 billion in total incentive funds while spending an estimated $150-180 million per year to cover 10% of the new enrollees’ costs. (72) (69) (68)

Figure 18

Targeted Relief for Affected Industries

ARP includes targeted subsidies for a number of public and private sector industries the pandemic has hit especially hard. Funding available nationwide include:

- Public Transit – A total of $28 billion for public transportation authorities. Twelve urban areas that include parts of Tennessee are expected to get a total of $113 million, and Tennessee’s remaining rural areas will receive an estimated $10 million.(73) (74) (6)

- Airports & Aviation – $15 billion to offset payroll costs and avoid layoffs for airline employees, $3 billion to do the same for aviation manufacturing, and another $8 billion for commercial airports. All airports in Tennessee will receive grants, but the allocations have not yet been finalized.(75)

- Restaurants – A total of $29 billion for grants to restaurants and bars that experienced revenue declines between 2020 and 2019. Eligible establishments must apply through the U.S. Small Business Administration to access the funds, which will be based on revenue losses up to a maximum of $5 million for single restaurants and $10 million for restaurant groups.(76)

- Venues – $1.3 billion for grants to shuttered live event venues – including music venues, museums, movie theaters, playhouses, etc. This is the second round of funding for this program. Eligible establishments must apply through the U.S. Small Business Administration and may qualify for up to $10 million each.(77)

Housing and Social Services

The American Rescue Plan funds dozens of housing and social service programs related to various economic effects of the pandemic. Most of this funding will be distributed via existing formula grant programs administered by the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and Agriculture (USDA). Some of the larger appropriations include (5):

- Housing – $42 billion for rental assistance, housing vouchers, homelessness assistance, and other programs aimed at ensuring stable housing.

- Child Care – $46 billion for the Child Care and Development Block Grant Program, Head Start, and other childcare assistance programs. This does not include the expansion of the child care tax credit discussed earlier.

- Nutrition – $6.8 billion for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and other nutrition assistance programs.

Parting Words

With the end of the pandemic hopefully in sight, Tennessee will soon experience an unprecedented influx of federal funding. Whether state and local policymakers think they need this money or not, they must now decide what to do with it. Using these funds responsibly, without redundancy, and in line with federal rules will require careful planning and coordination between state, regional, and local authorities. If they can achieve this, however, Tennessee has an opportunity to address both short-term needs and long-term challenges to our health and prosperity.

[i] These municipalities are those that also directly receive federal Community Development Block Grant f(CDBG) funds based on specific metropolitan and urban designations, and the allocations are based on the CDBG formula. (21)

[i] TennCare estimated that a 6.2% point increase in the state’s federal Medicaid match represented about $554 million in FY 2020. (72) Based on these estimates, a 5% point increase is equivalent to a one-year $447 million increase in federal funding – without accounting for any changes in health care costs or enrollment in future years.

Editors Note: This report was updated on March 30, 2021 to provide additional detail for the method used to allocate fiscal aid to metropolitan cities.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Congressional Budget Office. The Budgetary Effects of Laws Enacted in Response to the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic, March and April 2020. [Online] June 2020. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-06/56403-CBO-covid-legislation.pdf.

- —. Additional Information About the Economic Outlook: 2021 to 2031 . [Online] February 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57014.

- —. Estimate for Divisions O Through FF of H.R. 133, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 . [Online] January 14, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-01/PL_116-260_div%20O-FF.pdf.

- —. Summary Estimate for Divisions M Through FF of H.R. 133, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. [Online] January 14, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-01/PL_116-260_Summary.pdf.

- —. Estimated Budgetary Effects of H.R. 1319, American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 . [Online] March 10, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57056.

- Federal Funds Information for States (FFIS). The ARP: Initial State Allocations, Estimates. [Online] March 12, 2021. https://ffis.org/PUBS/budget-brief/21/16.

- Tennessee Department of Health . “Daily Case Information” and “COVID Vaccine State Summary” Datasets. [Online] March 15, 2021. [Cited: March 15, 2021.] Available from https://www.tn.gov/health/cedep/ncov/data/downloadable-datasets.html.

- Chetty, Raj, et al. Real-Time Economics: A New Platform to Track the Impacts of COVID-19 on People, Businesses, and Communities Using Private Sector Data. Opportunity Insights. [Online] https://tracker.opportunityinsights.org/.

- Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR). Infrastructure Needs Inventory: Data Explorer. [Online] [Cited: March 16, 2021.] https://www.tn.gov/tacir/infrastructure/data-explorer.html.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Evidence Used to Update the List of Underlying Medical Conditions that Increase a Person’s Risk of Severe Illness from COVID-19. [Online] November 2, 2020. [Cited: March 24, 2021.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/evidence-table.html.

- The University of Tennessee Knoxville. Tennessee Pulse Survey: Time Series Data. [Online] 2020. [Cited: March 16, 2021.] http://core19.utk.edu/tn-pulse-timeseries.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2019 – May 2020. [Online] May 21, 2020. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2020-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2019-dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm.

- Federal Funds Information for States. COVID-19: Treasury. [Online] January 26, 2021. [Cited: March 15, 2021.] https://ffis.org/COVID-19/treasury.

- U.S. Department of Treasury Office of Inspector General. Coronavirus Relief Fund Reporting and Record Retention Requirements. [Online] July 2, 2020. Available from http://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/Documents/Treasury_Office_of_Inspector_General_Coronavirus_Relief_Fund_Recipient_Reporting_and_Record_Keeping_Requirements___OIG-CA-20-021.

- —. Coronavirus Relief Fund Reporting Requirements Update. [Online] July 31, 2020. Available from https://ffis.org/sites/default/files/public/treasury_office_of_inspector_general_coronavirus_relief_fund_recipient_reporting_update_oig-ca-20-025_1.pdf.

- —. Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions Related to Reporting and Recordkeeping (Revised) . [Online] September 21, 2020. Available from https://ffis.org/sites/default/files/public/treasury_oig-_crf_faqs_september_2020_updates_pdf.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Treasury. Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions – Updated as of July 8, 2020. [Online] July 8, 2020. Available from https://treasurer.mo.gov/pdf/Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Frequently-Asked-Questions.pdf.

- —. Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions – Updated as of October 19, 2020. [Online] October 19, 2020. Available from https:/gfoaorg.cdn.prismic.io/gfoaorg/ac76b69e-65b3-46b4-a2d8-5a91ca3ccb54_Updated_CRF_FAQs10-19-2020.pdf.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Inspector General. Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions Related to Reporting and Recordkeeping (Revised). [Online] November 25, 2020. Available from https://gfoaorg.cdn.prismic.io/gfoaorg/22113339-bc08-4708-988d-a1adf8f2d726_Treasury+OIG+FAQs+November+Update.pdf.

- U.S. Senate Democratic Caucus. State and Local Fiscal Aid: Allocation Estimates. [Online] March 8, 2021. Downloaded from https://www.democrats.senate.gov/final-state-and-local-allocation-output-030821.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Community Development Block Grants Program. [Online] [Cited: March 23, 2021.] https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/cdbg.

- U.S. Congress. H.R. 1319. [Online] [Cited: March 15, 2021.] https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr1319/BILLS-117hr1319enr.pdf.

- Town of Saulsbury, Tennessee. Report on Financial Statements and Additional Information – Year Ended June 30, 2020. [Online] 2020. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/la/advanced-search/2020/city/1848-2020-c-saulsbury-rpt-cpa89-1-04-21.pdf.

- U.S. Senate Democratic Caucus. The American Rescue Plan – Summary of Senate Modifications to the House Bill. [Online] March 2021. [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/ARP%20Summary%20of%20Modifications%20in%20the%20Senate%20Bill.pdf.

- National Asssociation of Counties (NACo). U.S. Senate’s American Rescue Plan Coronavirus State & Local Fiscal Recovery Fund. [Online] March 8, 2021. https://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/NACo-Analysis-of-State-and-Local-Recovery-Funds_March-8-2.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Revenue. Monthly Collections Spreadsheets. [Online] [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://www.tn.gov/revenue/tax-resources/statistics-and-collections/monthly-collections-spreadsheets.html.

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee State Budgets for FYs 2020-2022. [Online] Available from https://www.tn.gov/finance/fa/fa-budget-information/fa-budget-archive/fiscal-year-2021-2022-budget-publications.html.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. February Revenues. [Online] March 12, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/finance/news/2021/3/12/february-revenues.html.

- Tennessee Department of Revenue. Notice #19-05 Local Sales Tax Reporting by Out-of-State Dealers. [Online] June 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/revenue/documents/notices/sales/sales19-05.pdf.

- National Association of State Budget Officers. The Fiscal Survey of States: Fall 2020. [Online] October 2020. https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states.

- Rosewicz, Rose, Theal, Justin and Fall, Alexandre. Pandemic Drives Historic State Tax Revenue Drop. Pew. [Online] February 17, 2021. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2021/02/17/pandemic-drives-historic-state-tax-revenue-drop.

- Urban Institute Tax Policy Center. State Revenues Showed Mixed Picture in January and Remain Down in Half of States Since the Onset of the Pandemic. [Online] March 2021. (Subscription Required) https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/projects/state-tax-and-economic-review/data-subscriptions.

- U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means. Section-by-Section Summary: Subtitle A — Crisis Support for Unemployed Workers. [Online] February 2021. [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/1.UI_sxs.pdf.

- U.S. Senate Democratic Caucus. Section-by-Section Summary: The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (H.R. 1319). [Online] February 21, 2021. [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://budget.house.gov/sites/democrats.budget.house.gov/files/documents/ARP%20Act%20SxS%20-%20as%20of%2002.22.21.pdf.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. What It Means For States: The America Rescue Plan Act Provisions. [Online] March 2021. [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/statefed/The-American-Rescue-Plan-Act-Provisions_v01.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Advisory: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 9-21. [Online] December 30, 2020. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_9-21.pdf.

- Congressional Research Service. Unemployment Insurance Provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (Division N, Title II, Subtitle A, the Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020). [Online] January 11, 2021. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11723.

- U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. Advisory: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 14-21. [Online] March 15, 2021. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_14-21.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Data. [Online] [Cited: March 12, 2021.] https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims.asp.

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Tennessee Unemployment Claims Data: Week Ending on March 6, 2021. [Online] March 11, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/general-resources/news/2021/3/11/tennessee-unemployment-claims-data.html.

- Congressional Research Service. Memo: State-Level Estimates of Eligibility for a Proposed Third Direct Payment. [Online] March 3, 2021. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/State-Level%20Estimates%20for%20a%20Proposed%20Third%20Direct%20Payment%20v2.pdf.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. The CARES Act Provides Assistance to Workers and Their Families. [Online] April 2020. [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/cares/assistance-for-american-workers-and-families.

- —. Treasury and IRS Begin Delivering the Second Round of Economic Impact Payments to Millions of Americans. [Online] December 29, 2020. [Cited: March 10, 2021.] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1224.

- U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Statistics for Tax Returns with EITC – 2020 (TY 2019). [Online] December 2020. [Cited: March 24, 2021.] https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. American Rescue Plan Act Will Help Millions and Bolster the Economy. [Online] March 15, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/american-rescue-plan-act-will-help-millions-and-bolster-the-economy#tax.

- Tax Policy Center. What is the Earned Income Tax Credit? Urban Institute and Brookings Institution. [Online] 2020. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-earned-income-tax-credit.

- U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Earned Income and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Tables. [Online] [Cited: March 15, 2021.] https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/earned-income-and-earned-income-tax-credit-eitc-tables.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-Year 2019 Estimates. [Online] September 2020. [Cited: March 15, 2021.] Data retrieved from https://www.data.census.gov.

- Fox, Liana. The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2019. [Online] September 15, 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-272.html#:~:text=Beginning%20in%202011%2C%20the%20U.S.,in%20the%20official%20poverty%20measure.

- Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy. A Poverty Reduction Analysis of the American Family Act, H.R. 1560, 116th Congress. [Online] January 25, 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/600f2123fdfa730101a4426a/1611604260458/Poverty-Reduction-Analysis-American-Family-Act-CPSP-2020.pdf.

- LaJoie, Taylor. Treasury Audit Highlights the Need for Clearer Eligibility Guidelines for the EITC. Tax Foundation. [Online] May 5, 2020. https://taxfoundation.org/treasury-audit-eitc-eligibility-guidelines/.

- Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration. Office of Audit Highlights: Improper Payments. [Online] April 30, 2020. https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2020reports/202040025_oa_highlights.html#:~:text=The%20IRS%20estimates%2025.3%20percent,Fiscal%20Year%202019%20were%20improper.

- Rachidi, Angela. Why the Child Tax Credit is the Worng Policy for Low-Income Families. American Enterprise Institute. [Online] December 19, 2019. https://www.aei.org/poverty-studies/why-the-child-tax-credit-is-the-wrong-policy-for-low-income-families/.

- Sawhill, Isabel V. and Pulliam, Christopher. Lots of Plan to Boost Tax Credits: Which is Best? Brookings Institution. [Online] January 15, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/research/lots-of-plans-to-boost-tax-credits-which-is-best/.

- Rachidi, Angela and Cherry, Robert. Reform EITC to Support Married Couples & Working-Class Families. American Enterprise Institute. [Online] January 20, 2021. https://www.aei.org/op-eds/reform-eitc-to-support-married-couples-working-class-families/.

- Congressional Research Service. Memo: Estimated FY2021 Grants to States and Institutions of Higher Education Under the Education Stabilization Fund Based on the Senate-Passed Substitute to H.R. 1319. [Online] March 8, 2021. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CD%20memo_ESSER_EANS_HEERF_Senate%20passed%20sub%20to%20HR1319_3-8-21.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Education. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund: CARES Act Allocations. [Online] April 2020. https://oese.ed.gov/files/2020/04/ESSER-Fund-State-Allocations-Table.pdf.

- —. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER II). [Online] January 5, 2021. https://oese.ed.gov/files/2021/01/Final_ESSERII_Methodology_Table_1.5.21.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Education. Questions and Answers: Elementary and Secondary School Relief (ESSER) Fund 2.0 Allowable Costs. [Online] January 13, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/health-&-safety/ESSER%202.0%20FAQ.pdf.

- —. 2020 Annual Statistical Report . [Online] [Cited: March 21, 2021.] https://www.tn.gov/education/data/department-reports/2020-annual-statistical-report.html.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Disaster Relief Fund: Monthly Report as of January 31, 2021. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. [Online] February 10, 2021. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_february-2021-disaster-relief-fund-report.pdf.

- —. FEMA Statement on 100% Cost Share . [Online] February 3, 2021. https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20210203/fema-statement-100-cost-share.

- Park, Edwin and Corlette, Sabrina. American Rescue Plan Act: Health Coverage Provisions Explained. Georgeown University Health Policy Institute. [Online] March 11, 2021. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/American-Rescue-Plan-v2-3.pdf.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2021 Federal Health Insurance Exchange Weekly Enrollment Snapshot: Final Snapshot. [Online] January 12, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2021-federal-health-insurance-exchange-weekly-enrollment-snapshot-final-snapshot.

- —. 2021 Special Enrollment Period Report. [Online] March 3, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2021-marketplace-special-enrollment-period-report.

- —. 2020 OEP State, Metal Level, and Enrollment Status Public Use File . [Online] April 2, 2020. Available from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Marketplace-Products/2020-Marketplace-Open-Enrollment-Period-Public-Use-Files.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map. [Online] March 8, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/.

- Tennessee General Assembly Fiscal Review Committee. Fiscal Note: HB 2529-SB 2526. [Online] March 7, 2020. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/111/Fiscal/HB2529.pdf.

- Rudowitz, Robin, Corallo, Bradley and Garfield, Rachel. New Incentive for States to Adopt the ACA Medicaid Expansion: Implications for State Spending. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] February 18, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/new-incentive-for-states-to-adopt-the-aca-medicaid-expansion-implications-for-state-spending/.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2019 1-Year Estimates. [Online] Sepetember 2019. Data retrieved from http://data.census.gov.

- Garfield, Rachel and Orgera, Kendal. The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] January 21, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/.

- Bureau of TennCare. FY 2022 Governor’s Budget Hearing. [Online] November 10, 2020. Video available at https://sts.streamingvideo.tn.gov/Mediasite/Play/05da57e66ab24c1d8c66b10dbe9b8ec71d?catalog=4051b7583650455881c5d67ab998921721&playFrom=0&autoStart=true.

- U.S. Senate Democratic Caucus. American Rescue Plan – 5307 Runs (Urbanized Areas). [Online] March 8, 2021. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/American%20Rescue%20Plan%20Act%20-%205307%20Runs%20(Tentative)%203.8.21.pdf.

- —. American Rescue Plan Act 533 Amounts – Formula Grants for Rural Areas. [Online] March 8, 2021. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/American%20Rescue%20Plan%20Act%205311%20Amounts%20(Tentative)%203.8.21.pdf.

- Federal Aviation Administration. Airport Rescue Grants. [Online] March 16, 2021. [Cited: March 24, 2021.] https://www.faa.gov/airports/airport_rescue_grants/.

- U.S. Chamber of Commerce. What You Need to Know About Restaurant Revitalization Fund Grants. [Online] March 24, 2021. [Cited: March 24, 2021.] https://www.uschamber.com/co/run/business-financing/restaurant-revitalization-fund-grants-guide.

- U.S. Small Business Administration. Shuttered Venue Operators Grant. [Online] [Cited: March 24, 2021.] https://www.sba.gov/funding-programs/loans/covid-19-relief-options/shuttered-venue-operators-grant.

Photo at top by Senate Democrats