On February 8, 2021, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee released his $41.8 billion recommendation for the state’s FY 2022 Budget — along with re-estimates and recommended changes for the FY 2021 Budget. (1) (2) The state budget represents our policymakers’ goals, the public goods and services intended to help meet those goals, and detailed plans to finance them. It is now the job of the legislature to consider and act on this recommendation.

Key Takeaways

- The recommendation reflects significant growth in expected revenue since the current budget passed in June 2020 – enough for a structural rebalance and a large increase in state spending.

- With less federal aid, Gov. Lee’s FY 2022 recommendation is 0.4% (or $166 million) lower than current fiscal year estimates. However, state revenue spending is 9.7% (or $1.9 billion) higher.

- The Budget projects state tax revenues will grow by 3.15% in FY 2021 – including 3.2% growth in General Fund revenues.

- The largest spending increases are recommended for capital improvements, rural economic development, salaries and benefits, K-12 education, TennCare, and local government grants.

- The largest spending reductions are recommended in TennCare, Human Services, and Corrections.

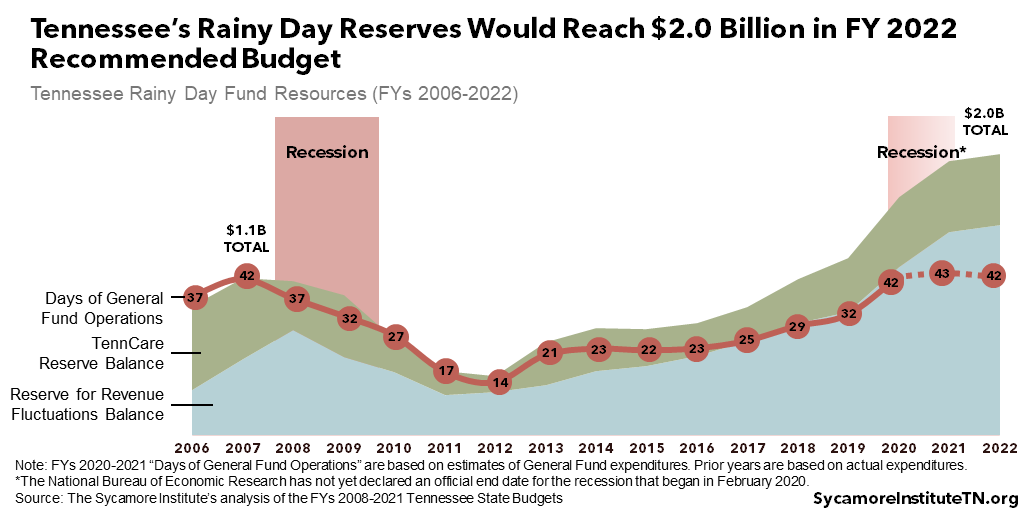

- The two main rainy day reserves combined would total $2.0 billion in FY 2021 and cover about 42 days of General Fund operations — about the same as in FY 2007 before the Great Recession

Recommended Reading

Our Tennessee State Budget Primer provides deeper discussions, related information, additional context, and a glossary of terms for the governor’s current budget recommendation.

General Fund Overview

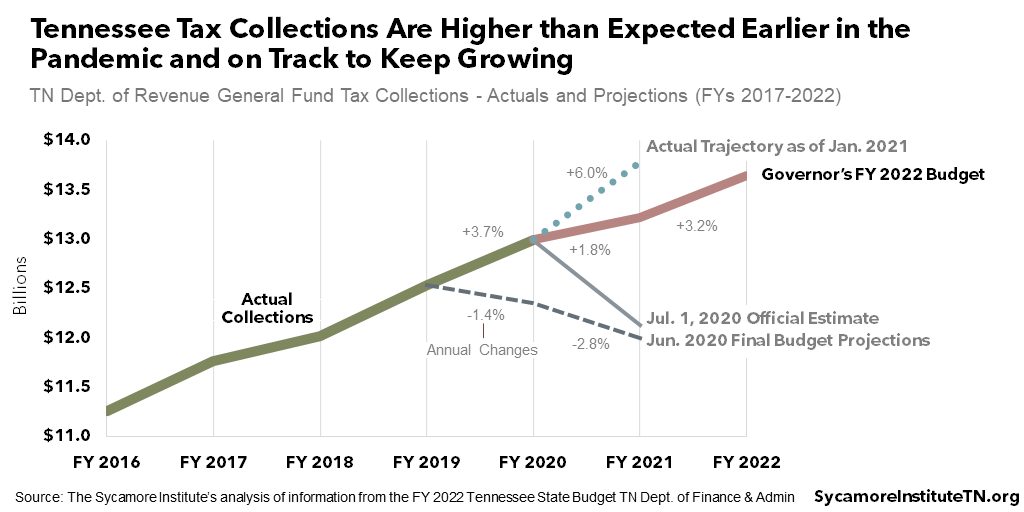

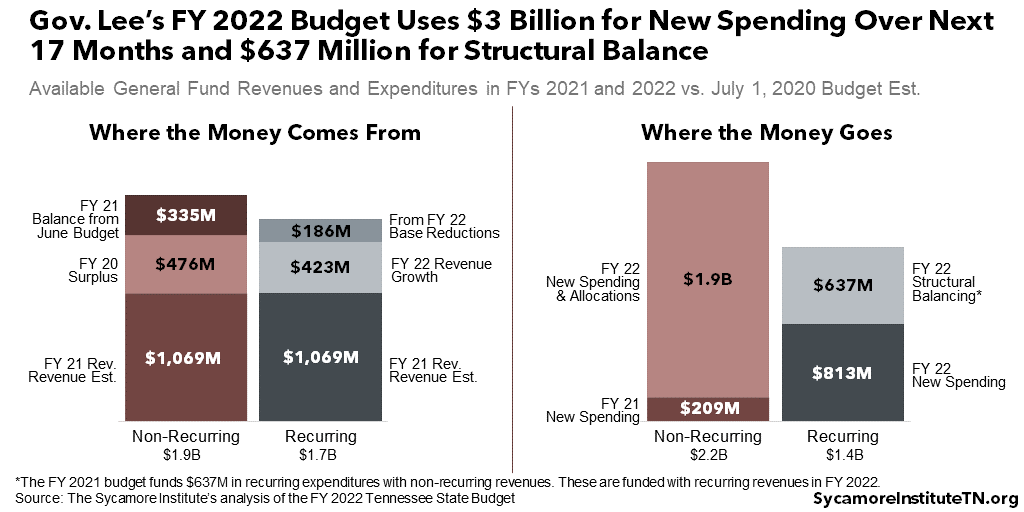

The FY 2022 recommended budget reflects a significant shift in revenue expectations compared to the current budget passed in June 2020 (Figure 1). At that time, the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on state revenues remained unclear. Now, the Lee administration expects General Fund revenues to grow 1.8% in the current fiscal year and another 3.2% in FY 2022 – generating $1.1 and $1.5 billion more revenue, respectively, than is currently budgeted for FY 2021. An additional $1.0 billion is also available from an FY 2020 end-of-year surplus, reducing certain programs next year, and other revenues and balances (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

The recommendation uses $637 million of this money to put the budget back into structural balance in FY 2022. A “structurally balanced” budget uses recurring revenues to cover recurring expenses. In the current budget, however, lawmakers used $637 million in non-recurring revenues (e.g. reserves) and spending reductions to offset expected recurring revenue losses. The governor’s FY 2022 proposal fully covers recurring expenses with recurring revenues – restoring structural balance without the large cuts policymakers braced for last June.

Gov. Lee proposes to use the remaining $3.0 billion in available funds for new General Fund spending and allocations over FYs 2021 and 2022 (Figure 2). The new recurring and one-time spending and allocations are laid out in more detail in the sections that follow.

About $274 million of new recurring revenues pay for one-time spending – reflecting concerns that some of the recent gains may not last. Consumer spending, which drives the state’s sales tax collections, has shifted significantly since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Some of the better-than-expected collections have come from a rise in durable goods purchases (e.g. appliances, furniture, electronics). Since consumer spending on one-time items may not translate to long-term revenue growth, the administration chose to use a portion of the new recurring money for non-recurring purposes. (4)

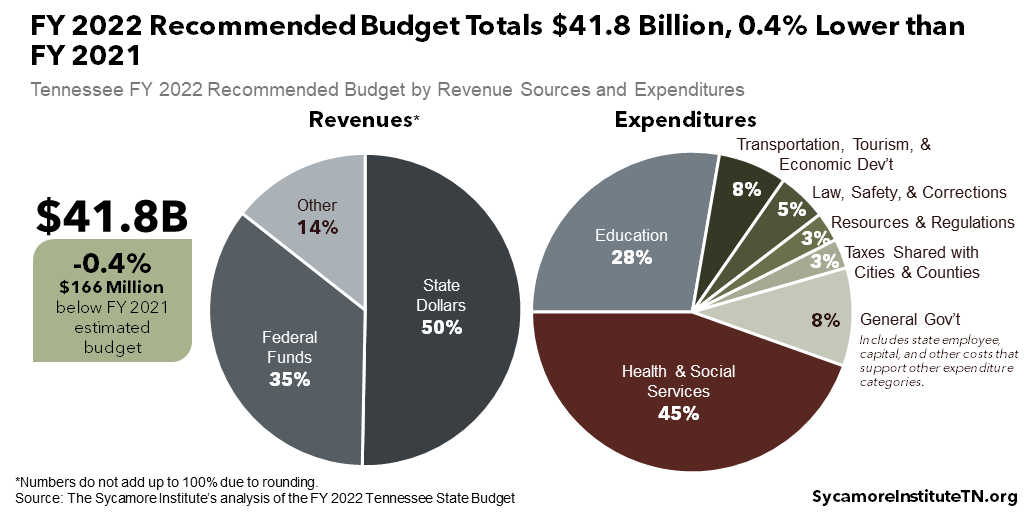

Figure 3

The FY 2022 Recommended Budget

The FY 2022 recommended budget totals $41.8 billion from all revenue sources, a drop of 0.4% (or $166 million) below estimates for the current fiscal year. The funding mix is 50% state dollars, 35% federal funding, and 14% from tuition and other sources. Education (28%) and Health and Social Services (45%) account for nearly three-quarters of total expenditures (Figure 3).

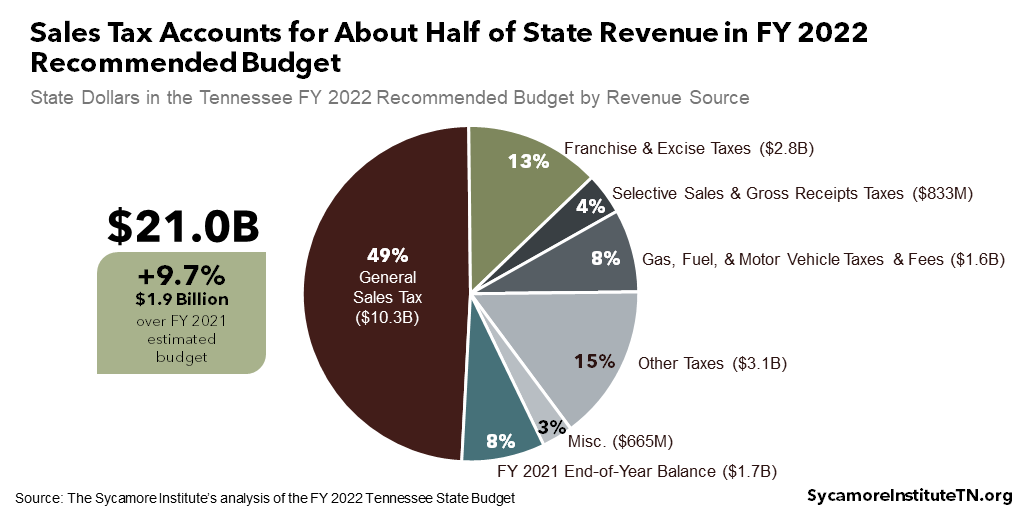

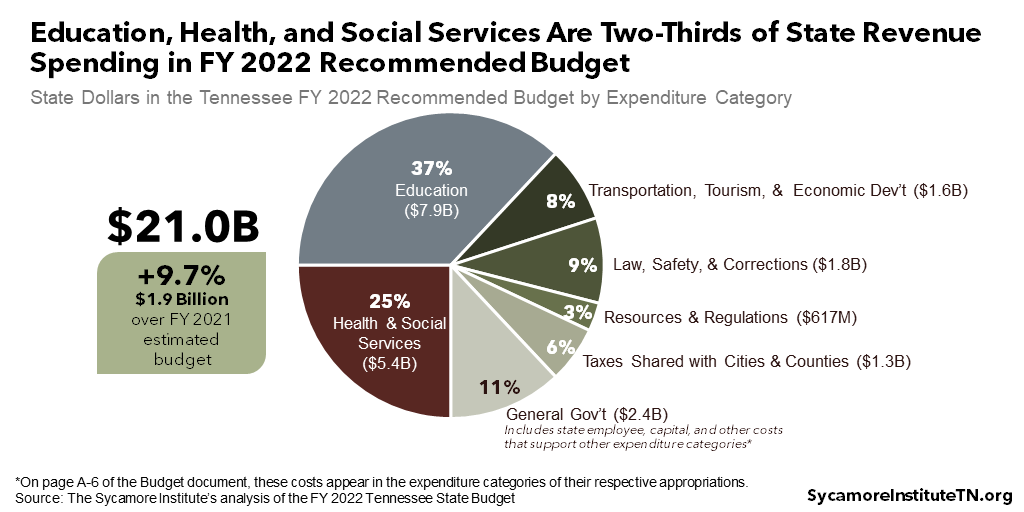

State dollars in the recommended budget total $20.1 billion, an increase of 9.7% (or $1.9 billion) from the current year. State revenues mostly come from the sales tax (49%) and taxes on businesses (13%) (Figure 4). Education (37%) and Health and Social Services (26%) account for just over 60% of expenditures from state appropriations (Figure 5).

Figure 4

Figure 5

The General Fund in Context

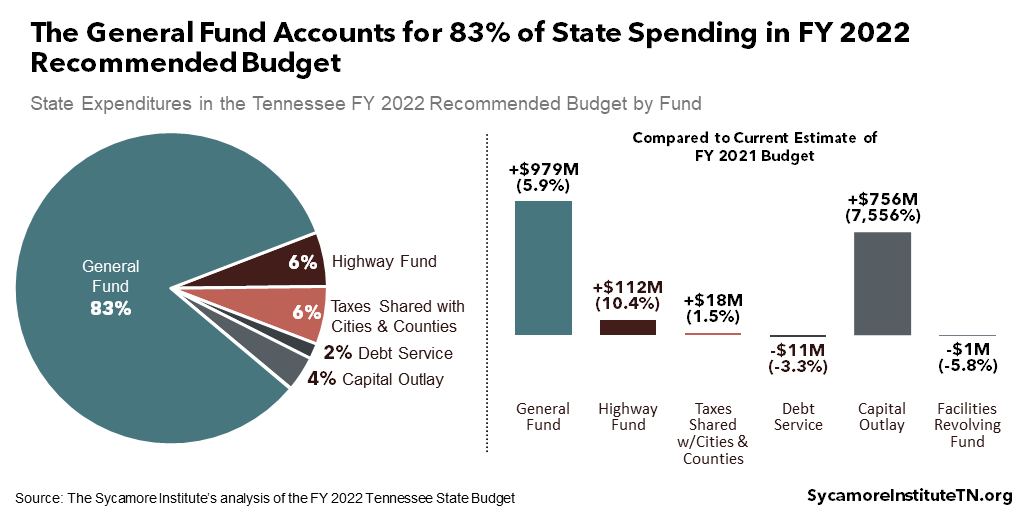

The administration’s budget document and presentations often focus on state dollars in the General Fund, which accounts for 83% of all state spending (Figure 6). That number does not include state appropriations for the Capital Outlay Program and Facilities Revolving Fund, which many discussions and calculations lump in with the General Fund because they are partly paid for with General Fund revenue.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Recommended Cost Increases and One-Time Spending

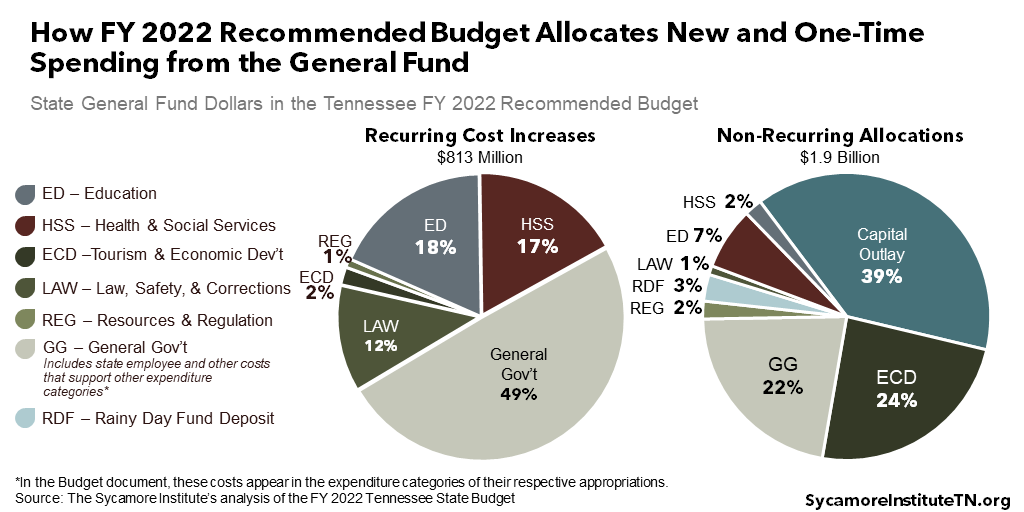

The Budget recommends $813 million in recurring General Fund spending increases and a total of $1.9 billion in non-recurring spending (Figure 7). In general, this additional money pays for rising costs in existing programs as well as the cost of new initiatives and investments.

The Budget’s Largest Recurring Increases

- +$219 million for K-12 education, including +$120 million for teacher pay and +$71 million to fund Basic Education Program (BEP) formula growth.

- +$150 million for personnel-related costs for state employees like salary and health insurance cost increases (excluding those for K-12 and higher education).

- +$135 million for higher education, including salary increases and outcomes-based formula increases for state colleges and universities that have achieved greater productivity.

- +$98 million for TennCare to cover expected cost increases, long-term services and supports for more enrollees, dental care for pregnant and postpartum women, and IT system upgrades. The additional state dollars will draw down about $230 million additional federal dollars.

- +$82 million for the Department of Correction for reimbursements to local governments for housing state prisoners in local jails, increased prisoner health care costs, and investments in re-entry and community supervision.

The Budget’s Largest Non-Recurring Allocations

- $888 million for capital improvements, maintenance, and IT/technology investments across state government.

- $454 million for rural and economic development and transportation, including $200 million for broadband expansion.

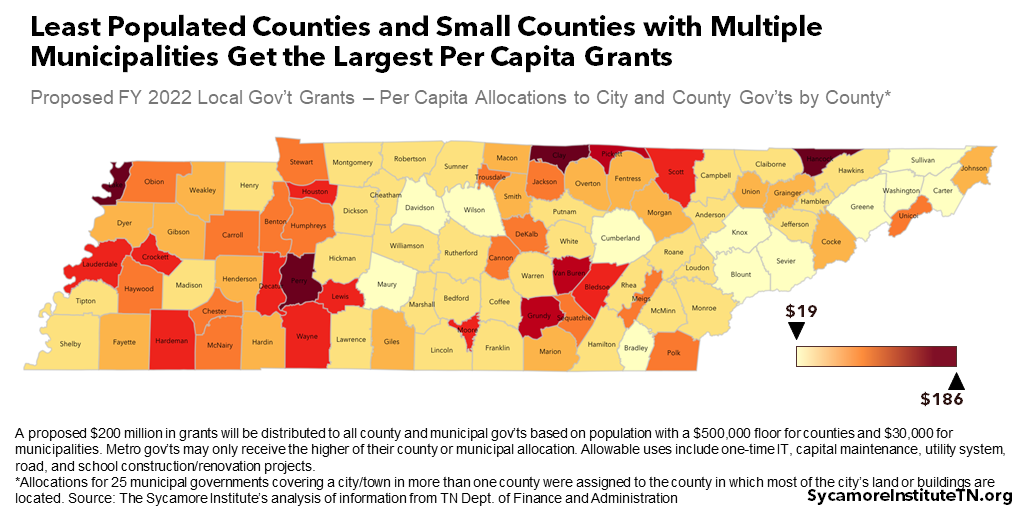

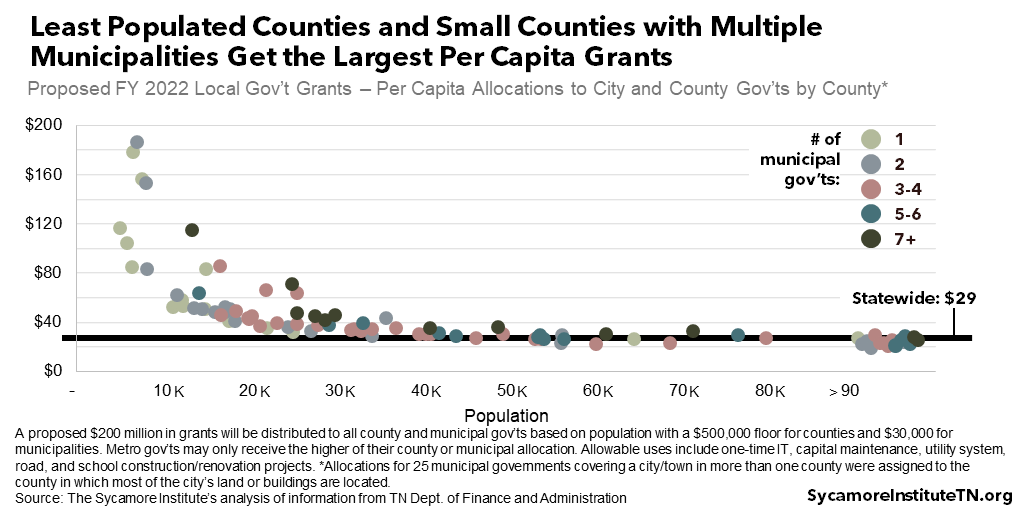

- $200 million for grants to local governments, divided equally between counties and municipalities for one-time IT, capital maintenance, utility system, road, and school construction/renovation projects. Grants will be based on population with a $500,000 floor for counties and $30,000 for municipalities. (5)

- $150 million for COVID-19 response efforts.

- $104 million for K-12 education, including $67 million for learning loss legislation passed during the General Assembly’s January special session, $20 million to hold school districts harmless for COVID-related drops in enrollment, and $12 million for a charter schools facility fund.

Summary of Gov. Lee’s Policy Initiatives

Several of Gov. Lee’s new policy initiatives affect the FY 2022 recommended Budget in a significant way. The total recurring increases and one-time spending discussed in the previous section include the costs summarized below.

Pre-Pandemic Initiatives

The Budget revives many of the funding increases and allocations from the governor’s FY 2021 recommendation that were shelved when the pandemic hit. The FY 2022 budget restores about $230 million in recurring spending increases and $400 million in non-recurring allocations that were dropped during last year’s budget revisions. These include efforts surrounding support for K-12 teachers, school choice, criminal justice reform, rural economic development, capital improvements, and access to care. Examples of some of the larger investments first proposed for FY 2021 that were not included or reduced in the FY 2022 recommendation include:

- $250 million non-recurring for a K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund. An estimated $5-8 million in annual interest earnings off the fund’s investment would have supported mental health efforts in schools. The FY 2022 Budget instead proposes $7 million recurring for the same purpose (see below).

- $46 million recurring to enroll about 2,000 people from the waiting list for TennCare’s long-term services and supports. The FY 2022 Budget proposes a scaled back version – enrolling about 300 high-need individuals with $11 million recurring (see below).

- $40 million recurring to cut the state’s professional privilege tax in half. This is not included in the recommendation for FY 2022.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Capital & Technology Improvements

The governor’s recommendation includes a total of $933 million ($45 million recurring, $888 million non-recurring) for capital projects, maintenance, and technology.

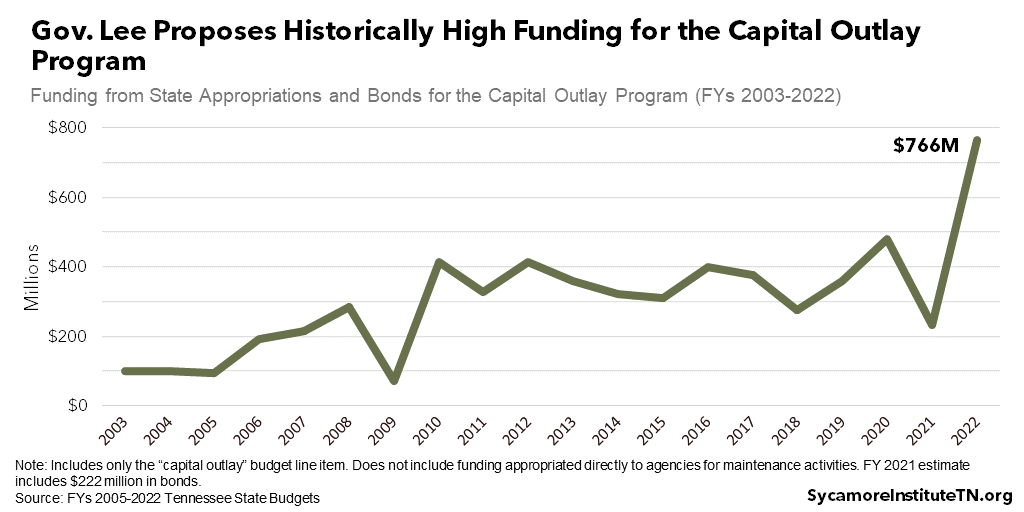

The Budget allocates $766 million non-recurring for the Capital Outlay program – its highest ever funding level (Figure 8). All projects that cost $100,000 or more are funded through the Capital Outlay program. Within the total are $393 million for improvements and major maintenance for state buildings and $372 million for higher education facilities.

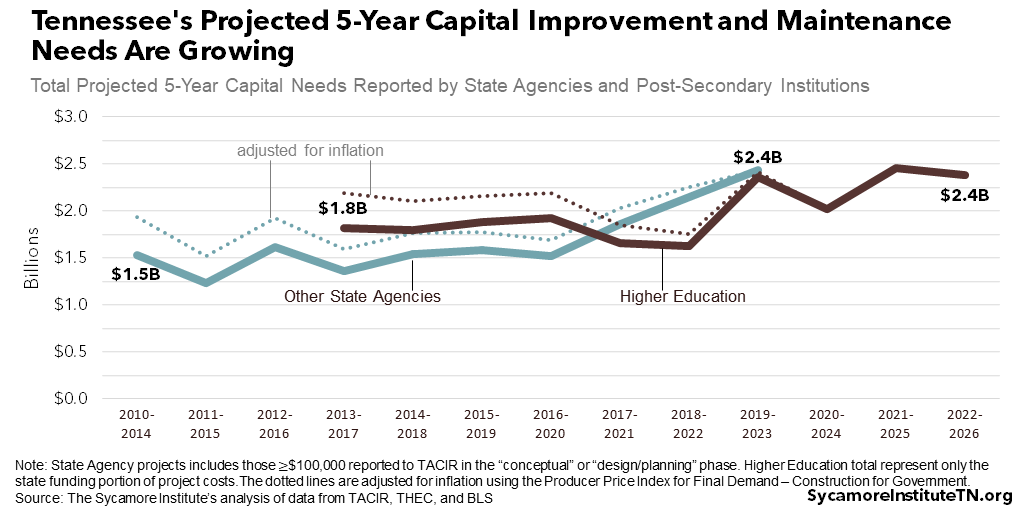

The state’s Capital Outlay needs have grown over the last decade and may exceed the available funding (Figure 9). Last November, for example, the Tennessee Higher Education Commission reported $633 million of capital improvement and maintenance needs for FY 2022 and another $1.7 billion over the subsequent four years. This represents a 31% increase from 10 years prior (9% after adjusting for inflation). (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) In 2019, other state agencies reported another $2.4 billion of potential capital needs through 2024 in the conceptual and planning phases – 59% more than a decade earlier (26% after adjusting for inflation). (6) (14)

The Budget recommends another $57 million for maintenance projects by specific departments, including a $20 million recurring increase and $37 million non-recurring. Within this total is $30 million non-recurring to address deferred maintenance of Tennessee State Parks and $10 million recurring increases for both higher education and general services.

Technology investments make up another $100 million, including a $24 million recurring increase and $86 million non-recurring. The largest of the investments are $43 million ($13 million recurring, $30 million non-recurring) for TennCare’s eligibility and data systems and $15 million non-recurring for IT modernization within the Department of Environment and Conservation.

Rural Economic Development

The Budget includes $229 million for programs aimed at improving rural communities and their economies. Among the programs funded are $22 million non-recurring for Rural Economic Opportunity Grants and $2 million recurring for an Office of Rural Initiatives within the Tourist Development Department.

The largest investment is $200 million in non-recurring funding for broadband expansion. The funds would support grants and tax credits for local governments and private entities to expand broadband infrastructure to unserved and underserved areas. In a January 2021 report, the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR) estimated it would take about $149 million to reach to an estimated 37,000 unserved housing units in Tennessee. (15)

K-12 Teacher Pay

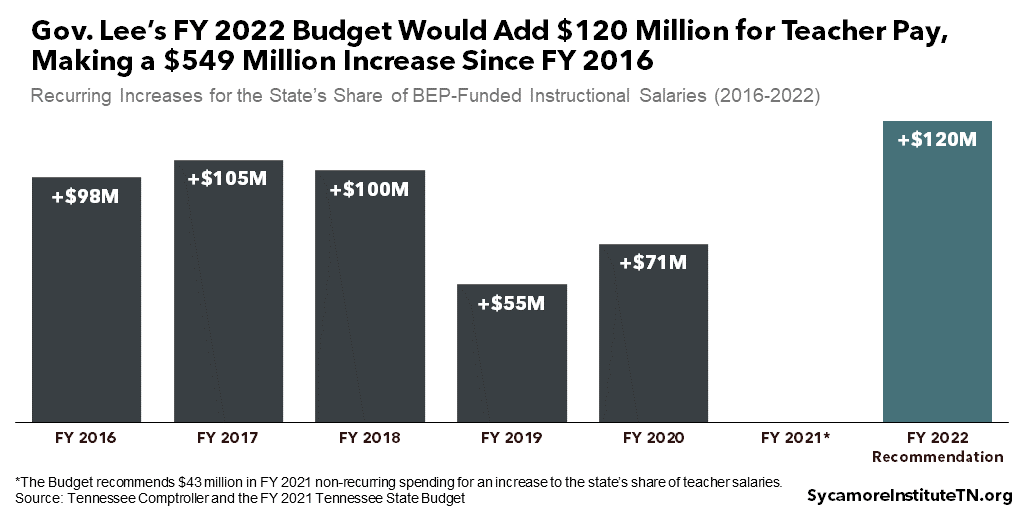

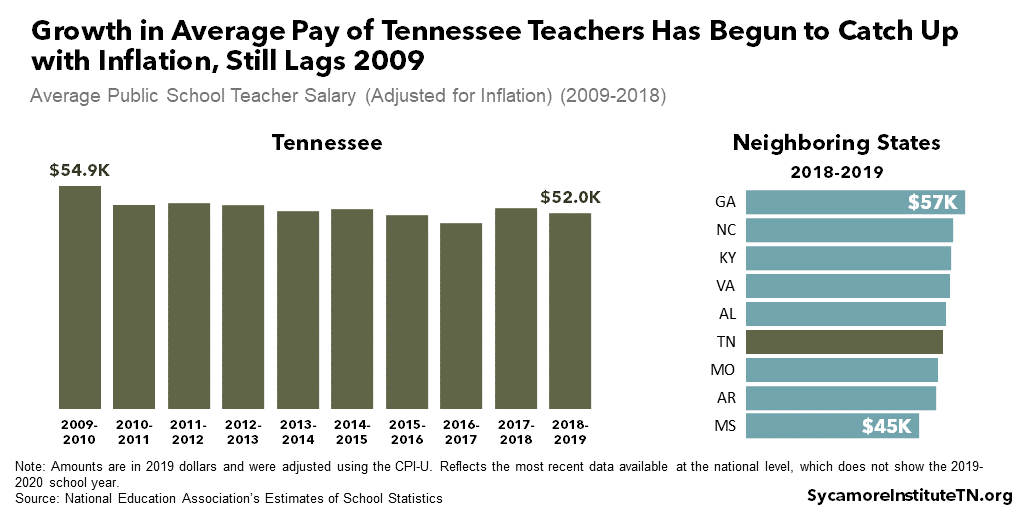

The increases for K-12 education include $120 million recurring for a 4% boost in the state’s contribution to local teacher salaries. Between FY 2016 and FY 2020, lawmakers enacted a total of $429 million in recurring increases for teacher pay (Figure 10). Since that time, growth in Tennessee teachers’ average pay has begun to catch up with inflation. After adjusting for inflation, however, teachers’ average pay during the 2018-2019 school year was still about 5.4% lower than a decade earlier (Figure 11). (16)

Figure 10

Figure 11

State policymakers have signaled an interest in making changes to ensure the proposed salary boost makes it to classroom teachers’ paychecks. (18) The funds are awarded to local districts through a component of the Basic Education Program (BEP) that supports instructional pay. State policymakers have expressed frustration that past increases for this purpose have not always translated to an equivalent boost in pay for all classroom teachers. A few reasons why that might have happened:

- Local Flexibility – The BEP is often described as “a funding formula, not a spending plan.” Funding for the different components drives overall BEP award amounts, but local districts have flexibility in how they allocate state funds. (19)

- Local Match – State BEP funds only cover a portion of local education costs.(19) For a 4% increase in the state contribution to become a 4% paycheck boost, local districts would also have to raise their own spending on BEP-funded teacher salaries by 4%.

- BEP Definitions – The instructional salary component of the BEP includes all personnel who are certified to teach, which can include both classroom teachers and administrators.(17)

- Non-BEP Teachers – Nearly all school districts employ more classroom teachers than they get funding for from the BEP.(17) As a result, across-the-board teacher raises would require most local districts to spend even more than what it takes to match BEP funds from the state.

Criminal Justice Reform

The Budget includes about $48 million for several proposals meant to reduce incarceration and improve outcomes for Tennesseans involved in the criminal justice system. Highlights include:

- $27 million related to re-entry services, including a $16 million recurring increase to boost state prisoner housing reimbursements for local jails that offer evidence-based re-entry services, $5 million in non-recurring grants to help local jails adopt these programs, a $4 million recurring increase for a proposed “Re-entry Success Act,” and a $2 million recurring increase for a re-entry employment initiative.

- $7 million recurring increase and $2 million non-recurring for behavioral health programs within the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services that serve people involved in the criminal justice system (e.g. support for recovery courts, criminal justice liaisons, and the “Creating Homes” initiative for re-entering populations).

- $3 million recurring for two new day reporting and community resource centers. Day reporting centers provide an alternative to incarceration.

- $3 million in non-recurring projects that could inform longer-term criminal justice reform efforts. These include $2 million for a criminal justice data infrastructure project and $1 million for a study of the state’s criminal code.

Access to Health Care

The Budget includes $29 million to expand access to health care, including a $22 million recurring increase and $6 million in non-recurring spending. Highlights include:

- $20 million for TennCare would increase access to long-term services and supports for about 300 new enrollees ($11 million recurring), dental care for pregnant and postpartum women ($2 million recurring), and coverage for adopted youth ($350,000 recurring). Also included is a five-year pilot to extend postpartum coverage for mothers on TennCare from 60 days to 12 months ($7 million non-recurring).

- $7 million recurring to expand access to mental health services for school-aged children. This replaces the governor’s FY 2021 proposal to establish a $250 million K-12 Mental Health Trust Fund – from which about $5-8 million in annual interest earnings would have supported the same purpose.

- $2 million recurring increase to expand the primary care safety net.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Grants to Local Governments

The budget recommends $200 million for one-time grants to local governments. The funding will be divided roughly equally between municipal and county governments for one-time IT, capital maintenance, utility system, road, and school construction/renovation projects. Grants will be based on population with a $500,000 floor for county governments and $30,000 for municipalities. (5) The least populated counties and small counties with more municipal governments are slated to get the most per capita from the proposed grants (Figures 12 and 13).

Recommended Spending Reductions

The Budget recommends ‑$186 million in recurring General Fund reductions. (2) These targeted decreases affect specific programs or departments that may still experience an overall funding increase.

The Budget’s Largest Recurring Base Reductions

- -$106 million from TennCare, including -$37 million due to the annual recalculation of Tennessee’s federal match rate and -$25 million from prescription drug savings.(2) This will result in a net decrease of about $129 million in federal funding.

- -$13 million from the Department of Human Services – the largest of which is -$8 million to temporary cash assistance under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. The reduction is associated with using education spending to fulfill the state’s maintenance of effort requirement for receiving federal TANF funding. This $8 million reduction is more than offset by restoring a non-recurring reduction that was made for FY 2021. Overall, recommended state funding for temporary cash assistance within DHS is $6.4 million, which is about $2.5 million above FY 2021 but about half that of recent years’ spending levels. (2)

- -$11 million from the Department of Corrections, including -$9 million from proposed legislation that would restructure the Community Corrections program.(2)

Funds Reserved for Legislative Action

The Budget reserves $3 million recurring and $15 million in non-recurring funds for initiatives and amendments of the legislature. (3) Another $13 million recurring and $20 million in non-recurring funds are reserved for the Administration Amendment expected later in the legislative session.

State Tax Revenue Growth

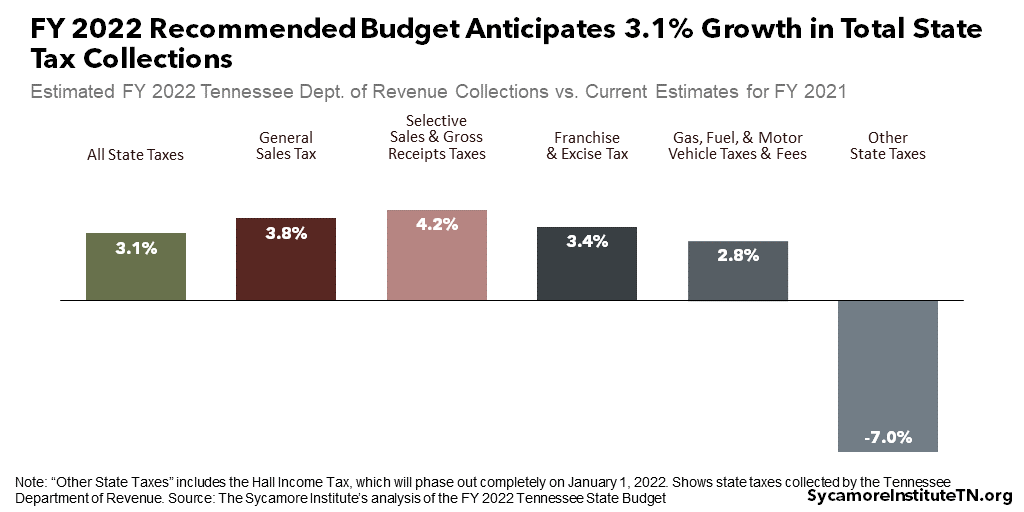

The Budget expects total state tax collections to grow by 3.15% (or $496 million) in FY 2022. The State Funding Board recommended a range of 2.5–3.0% growth in recurring Department of Revenue state tax revenues based on estimates from several experts, which ranged from 3.1-4.8%. (1) Recurring General Fund revenues make up about 84% of all Department of Revenue state tax collections and are expected to grow by 3.2% in FY 2022 (Figure 1).

Revenue Growth Highlights

The direction and degree of expected change varies by revenue type (Figure 14):

- +3.8% gain ($379 million) in general sales tax collections

- +4.2% gain ($33 million) in selective sales and gross receipts taxes collections

- +3.4% gain ($93 million) in franchise and excise tax collections from businesses

- +2.8% gain ($43 million) in gas, fuel, and motor vehicle taxes and fees collections

- -7.0% drop ($50 million) in other state taxes, including the Hall income tax phased out by the 2017 IMPROVE Act on January 1, 2021

Figure 14

Federal Funds and Coronavirus Relief

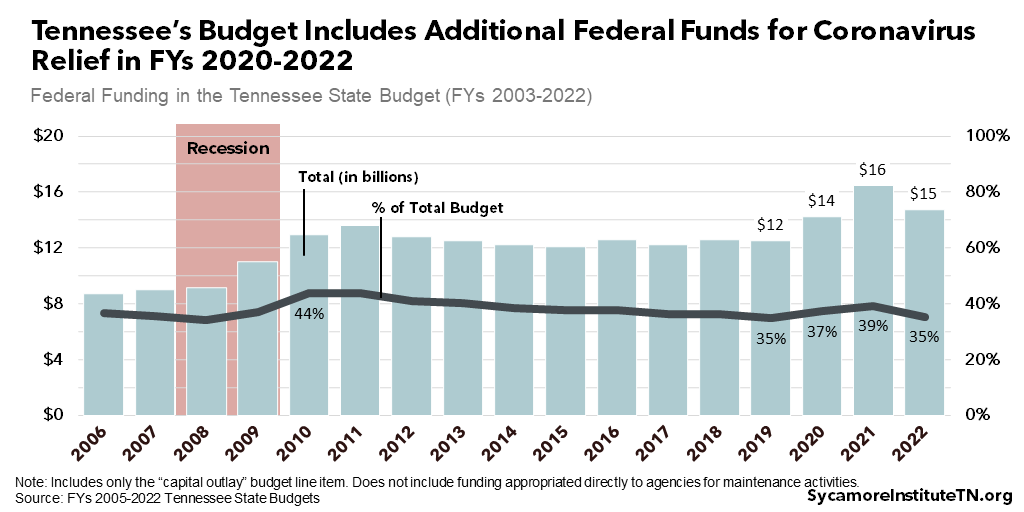

The FY 2022 Budget reflects a decline from current, higher-than-usual federal funding, which came from coronavirus relief bills that Congress passed in 2020. State budget estimates for FY 2021 reflect an historic amount of federal funding (Figure 15). Even with these additional dollars, however, the state’s budget is currently expected to rely less on federal funding this fiscal year than in the wake of the Great Recession. The governor’s proposal does not try to predict how much – if any – additional relief money Congress may give states in the coming months.

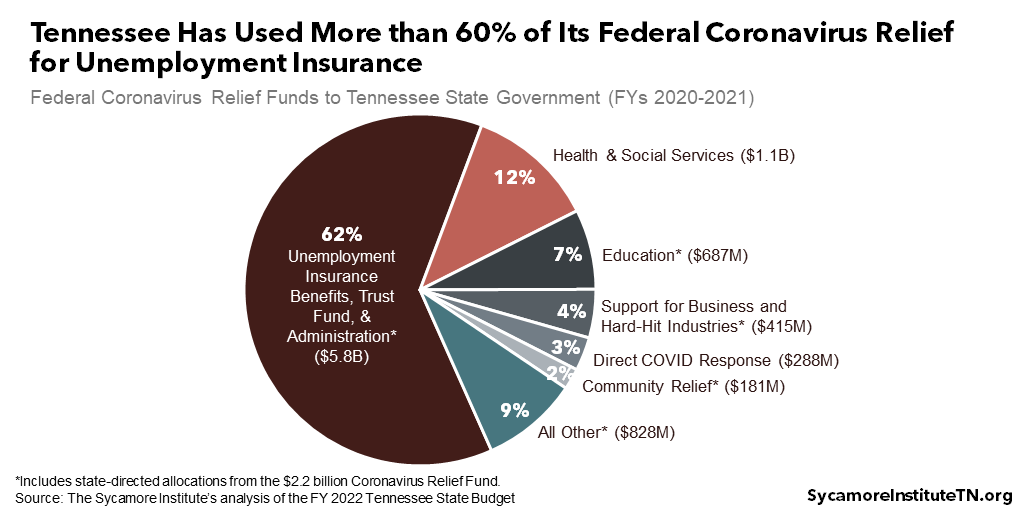

The Budget estimates Tennessee will receive a total of $9.3 billion from the federal coronavirus relief packages already enacted by Congress – not all of which flows through the state budget. Over 60% of this money ($5.8 billion) has gone to the unemployment insurance program (Figure 16). Most of it paid benefits and replenished the state’s unemployment trust fund to avoid a tax hike on employers by replenishing the state’s unemployment trust fund – neither of which appear in the state budget. The remaining federal relief funds have supported direct COVID-19 response efforts, other health and social services, education, and aid to small business, hard-hit industries, and communities.

Figure 15

Figure 16

Rainy Day Reserves

The Budget recommends a combined balance of $2.0 billion in the Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations and the TennCare Reserve by the end of FY 2022 (Figure 17). These rainy day reserves represent Tennessee’s ability to respond to an economic downturn. Reserve balances provide a cushion during a recession, which typically increases demand for state programs and services but decreases the revenues that fund them.

- This combined balance would give the budget about the same cushion it had just before the Great Recession. At $2.0 billion, the two reserves would cover about 42 days of state-funded General Fund operations at the governor’s recommended FY 2022 levels. That is one day less than the current budget but about the same as in FY 2007, when the combined balance was about $881 million lower.

- The Budget hits that mark by adding $50 million to the Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations in FY 2022. This deposit would grow that account to $1.5 billion — the highest dollar amount ever.

- The Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations would exceed its statutory target by $194 million. State law sets a target for that fund at 8% of General Fund revenues, and the FY 2022 recommended balance represents 9.2%[i].

Figure 17

Figure 18

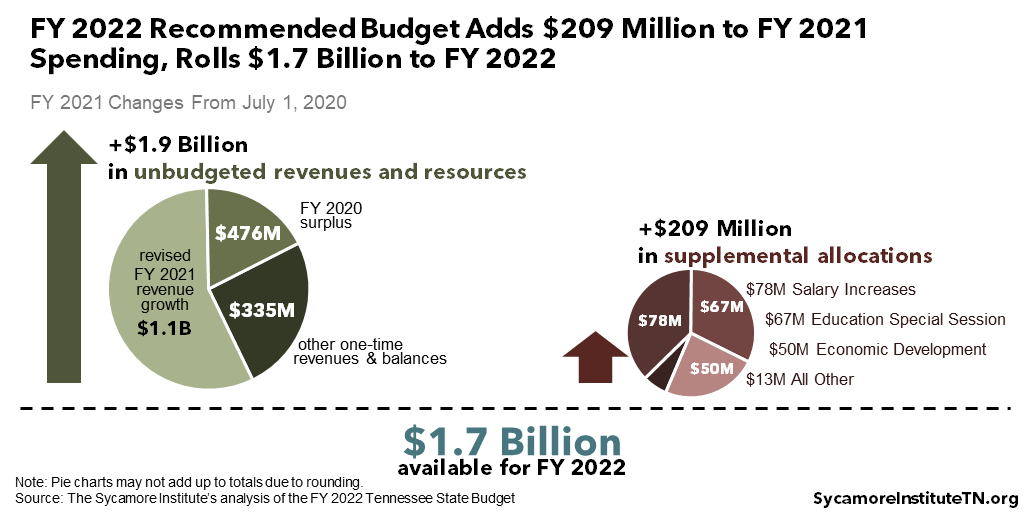

Changes to the FY 2021 Budget

The Budget includes $209 million of supplemental spending in FY 2021, the current fiscal year (Figure 18). These supplemental requests are common because actual revenues and spending needs are often higher or lower than originally estimated. Of the $209 million supplemental recommendation, the largest portions include:

- $78 million for salary increases – including a 2% raise retroactive to January 1, 2021 for state and higher education employees and for the state’s share of teacher salary costs.

- $67 million for learning loss legislation passed during the General Assembly’s special January session.

- $50 million for an undisclosed economic development project.

The Budget also anticipates $1.9 billion more money available for FY 2021 than was budgeted when the fiscal year began in July. These funds consist of a $476 million surplus from FY 2020, $1.1 billion in unbudgeted FY 2021 revenue collections, and a $335 million balance from the budget approved in June. Some of this money funds the supplemental spending items discussed above, while the remaining $1.7 billion will roll over to FY 2022 as non-recurring revenue to pay for non-recurring recommendations discussed earlier. (3)

Key FY 2022 Budget Documents and Resources

For more details on Gov. Lee’s FY 2022 recommended Budget, see the following documents and resources.

- FY 2022 Budget Document

- FY 2022 Budget: Volume 2 – Base Budget Reductions

- Budget Overview: FY 2022

- The Commissioner of Finance and Administration’s FY 2022 Budget Presentation

- FY 2022 Legislative Budget Hearings with the Commissioner of Finance and Administration:

[i] Calculated by adding Department of Revenue and Other State Revenue allocations to the General Fund, Education Fund, and Debt Service Fund minus the Gas Tax allocation to the Debt Service Fund (from page A-65 of the Budget).

References

Click to Open/Close

- State of Tennessee. FY 2021-2022 Tennessee State Budget. [Online] February 8, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/2022BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- —. FY 2021-2022 Tennessee State Budget: Volume 2 – Base Budget Reductions. [Online] February 8, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/2022BudgetDocumentVol2.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. January Revenues. [Online] February 12, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/finance/news/2021/2/12/january-revenues.html.

- —. Budget Overview: FY 2021-2022. [Online] February 4, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/overviewspresentations/22AdReq15i.pdf.

- —. Commissioner’s Presentation: FY 2022 Recommended Budget. [Online] February 9, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/overviewspresentations/FY22RecommendedBudget.pdf.

- —. 2021-22 Local Government Grants. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/finance/looking-for/2021-22-local-government-grants-.html.

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC). Capital Project Recommendations for 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, and 2019-20. [Online] Obtained from THEC on Feburary 18, 2021.

- —. 2015-16 Capital Project Recommendations. [Online] November 20, 2014. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/cm/2014/CMFall2014_I.D.%202015-16%20Capital%20Project%20Recommendations.pdf.

- —. 2016-17 Capital Project Recommendations. [Online] November 19, 2015. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/cm/2015/I.E._2016-17_Capital_Recommendations11-19-15.pdf.

- —. 2017-18 Capital Project Recommendations. [Online] November 16, 2016. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/cm/2016/VI_2017-18_Capital_Projects_Recommendations.pdf.

- —. 2018-19 Capital Project Recommendations. [Online] November 15, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/cm/2017/fall-2017/VII._Capital_Projects_Recommendations_Fall_2017.pdf.

- —. 2020-21 Capital Projects Recommendation. [Online] November 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/bureau/fiscal_admin/capital_outlay/capital-budget/captbudget/2020-21%20Capital%20Recommendation_TC.pdf.

- —. 2021-22 Capital Project Recommendations. [Online] November 6, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/cm/2020/fall/IV.%202021-22%20Capital%20Projects%20Recommendation.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. PPI Commodity Data for Final Demand-Construction for Government (WPUFD432). [Online] 2010-2021. [Cited: February 17, 2021.] Accessed via https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet.

- Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR). 2010-2019 5-Year Inventory Data from Building Tennessee’s Tomorrow: Infrastructure Needs Inventory . [Online] https://www.tn.gov/tacir/infrastructure/infrastructure-reports-/building-tennessee-s-tomorrow-2019-2024.html.

- —. Broadband Internet Deployment, Availability, and Adoption in Tennessee Four Years After the Broadband Accessibility Act. [Online] January 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tacir/2021publications/2021_BroadbandUpdate.pdf.

- National Education Association. Rankings of States and Estimates of School Statistics. [Online] [Cited: February 10, 2021.] Data accessed from https://www.nea.org/research-publications.

- Bergfeld, Tara and Wesson, Linda. Teacher Salaries in Tennessee, 2015-2018. Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury, Office of Research and Education Accountability. [Online] April 2019. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/orea/documents/orea-reports-2019/Salaries_FullReport.pdf.

- Tennessee General Assembly. Testimony and Statements before the Senate Finance, Ways, and Means Committee on February 4, 2020 and February 9, 2021. [Online] Video available at http://tnga.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=431&clip_id=21413 and http://tnga.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=614&clip_id=23836.

- Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. Basic Education Program. Officesof Research and Education Accountability. [Online] [Cited: February 5, 2020.] https://comptroller.tn.gov/office-functions/research-and-education-accountability/legislative-toolkit/bep.html.