Key Takeaways

- To earn a degree, students must cover the costs of school and life, which remain the single largest barrier to post-secondary enrollment and completion.

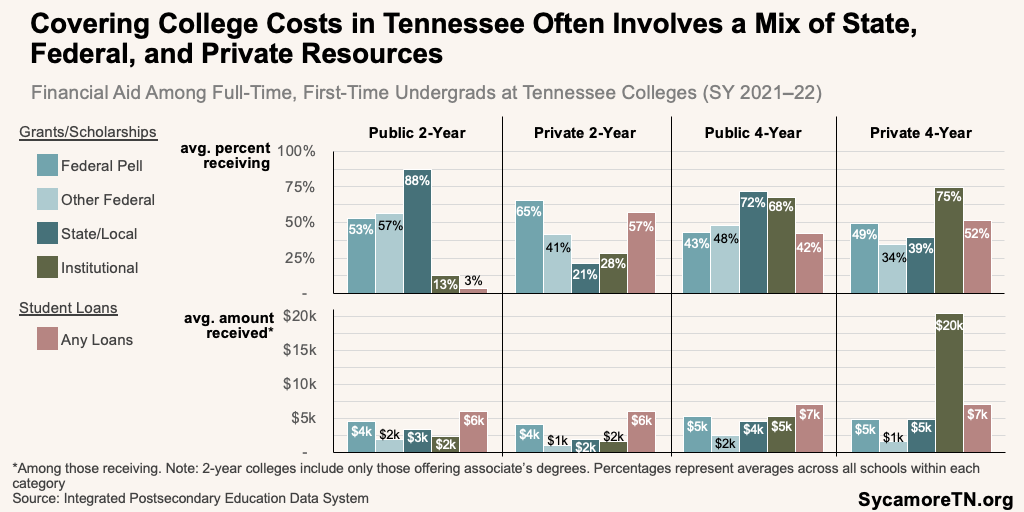

- Covering college costs often involves a mix of state, federal, and private resources.

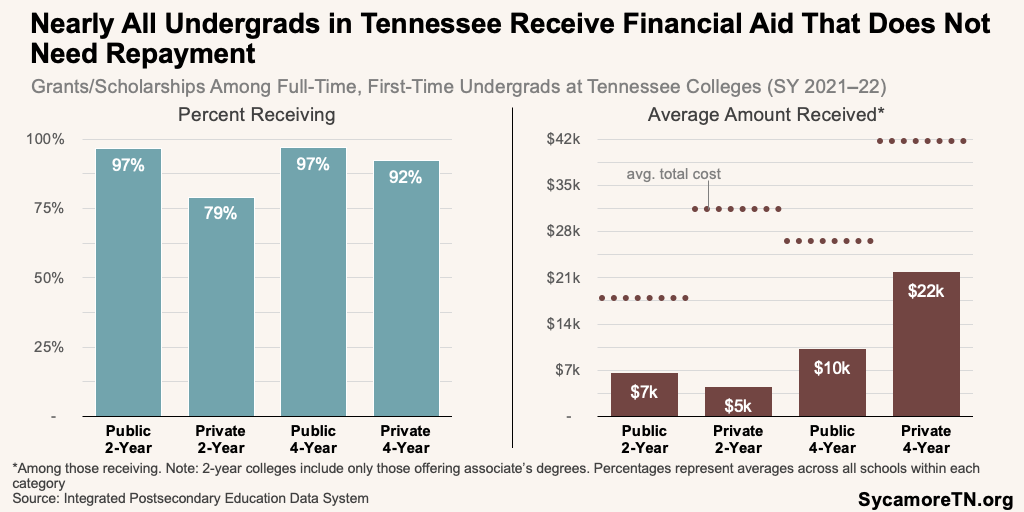

- Very few students face a college’s full “costs” out of pocket because nearly all students receive state, federal, or institutional aid that does not need repayment.

- Emerging issues and challenges include:

- Despite available resources, costs remain a barrier to attending and completing college for many students—as evidenced by the state’s experience with Tennessee Promise.

- Most studies generally agree that undergraduate degrees and debts taken on to pay for them usually have a positive return, but specific pathways and circumstances may not.

- Perceptions of college costs (i.e., sticker shock)—and not actual costs—influence if and where students attend college.

- Students may not access or retain needed grants and scholarships because of complexity and confusion.

- Statutory maximums limit several of Tennessee’s scholarships, which haven’t always kept up with inflation.

- The practice of private scholarship displacement can come with trade-offs for students, colleges, and the private entities that award the funds.

- Although they have expanded access to post-secondary education, Tennessee’s investments in community college may incentivize choices that make it harder for some to earn a degree.

- Federal requirements for “total cost of attendance” and financial aid may affect how schools estimate their costs and contribute to students’ sticker shock, confusion, or unexpected costs.

- Outside pressures—like those in the housing market—can increase student costs and create challenges for colleges and universities.

Post-secondary education can be a path to individual success and economic mobility. However, many Tennessee policymakers and families may find it confusing to discern the true “cost” of earning a degree and the many state, federal, and private resources available to cover those costs. This report sheds light on college costs in Tennessee, how students finance them, and related issues and challenges.

Background

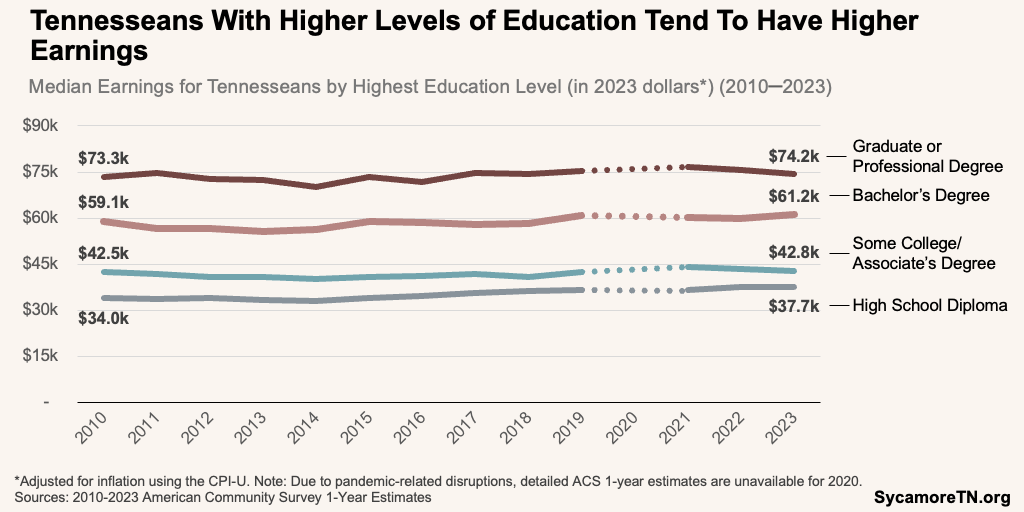

Post-secondary education is increasingly necessary for many jobs and an avenue to financial security. (1) According to one estimate, about 59% of “good jobs”—defined as paying at least $39,400 for Tennesseans ages 25-44 and $50,700 for those 45-64—required at least a bachelor’s degree in 2021. This share is expected to grow to 66% by 2031. (2) A college education is also associated with higher lifetime earnings for most graduates. (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) In fact, Tennesseans with higher education levels tend to have higher earnings (Figure 1), although individual experiences and career paths vary. (9) The career opportunities and higher earning potential that come with education are also associated with better health and well-being, higher social standing, and more community engagement. (1) (10) (7) More income also generates more investment, saving, and spending, which can improve the broader economy and community. (1)

Figure 1

Costs

To earn a degree, students must cover the costs of school and life, which remain the single largest barrier to post-secondary enrollment and completion. These costs can include tuition, mandatory fees, on- or off-campus housing, books, supplies, other school fees (e.g., lab fees, program fees, online course fees), transportation, food, and medical care. (12) To ultimately earn a degree, students must find a way to cover all these costs—often while forgoing full-time work to attend classes. In 2022, for example, only 7% of full-time and 37% of part-time college students ages 16-24 nationally worked full-time (i.e., 35 or more hours per week). (13) Cost is consistently cited as the top barrier to enrolling and completing college. (14) (15)

“Post-Secondary” in This Report

This report focuses on paying for post-secondary education at institutions that award associate or bachelor’s degrees. This report may collectively refer to these as post-secondary institutions or colleges and universities. Mentioned two-year schools are limited to those that offer associate’s degrees. Public two-year schools include Tennessee’s 13 community colleges and exclude Tennessee Colleges of Applied Technology (TCATs). Meanwhile, four-year institutions are those that award bachelor’s degrees. The public four-year universities in this report include four undergraduate schools that are part of the University of Tennessee system and six locally governed colleges and universities (e.g., MTSU, ETSU). (31)

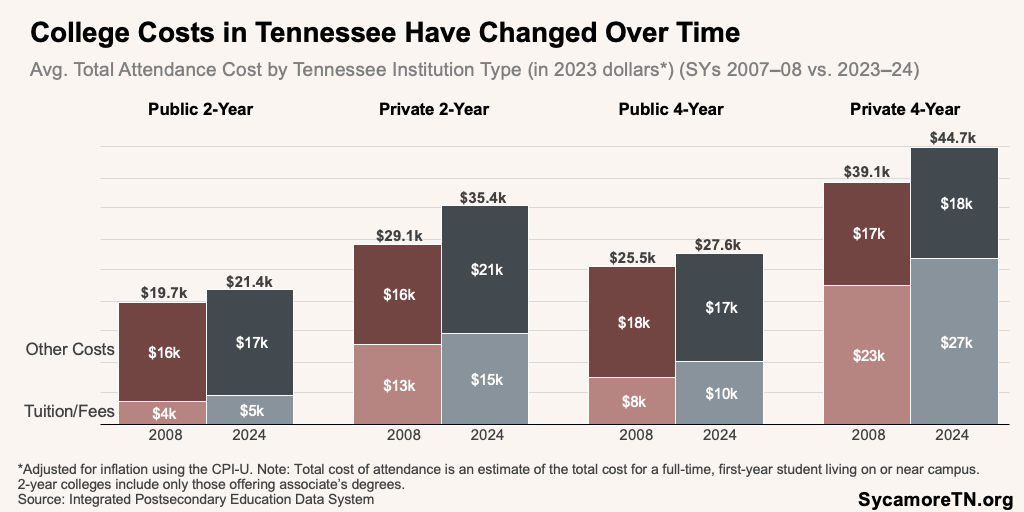

Figure 2

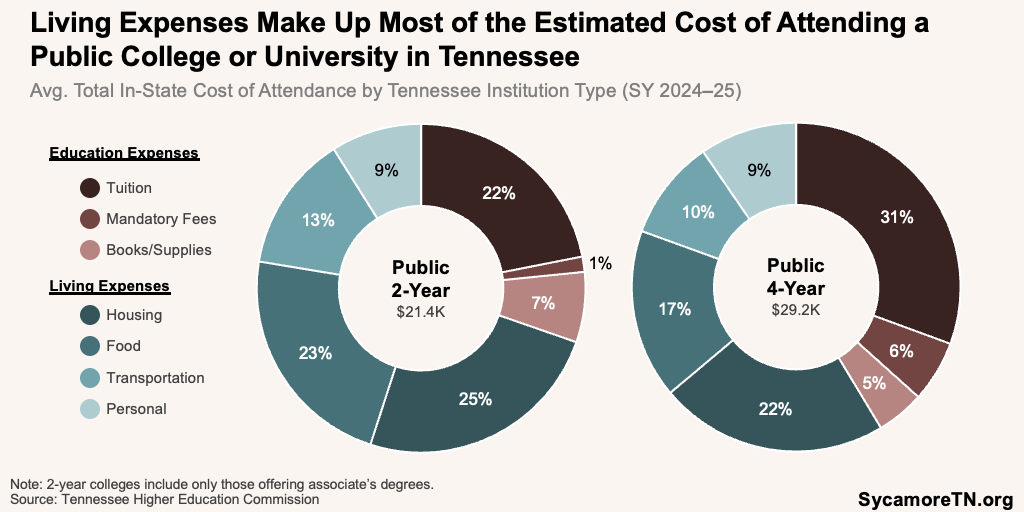

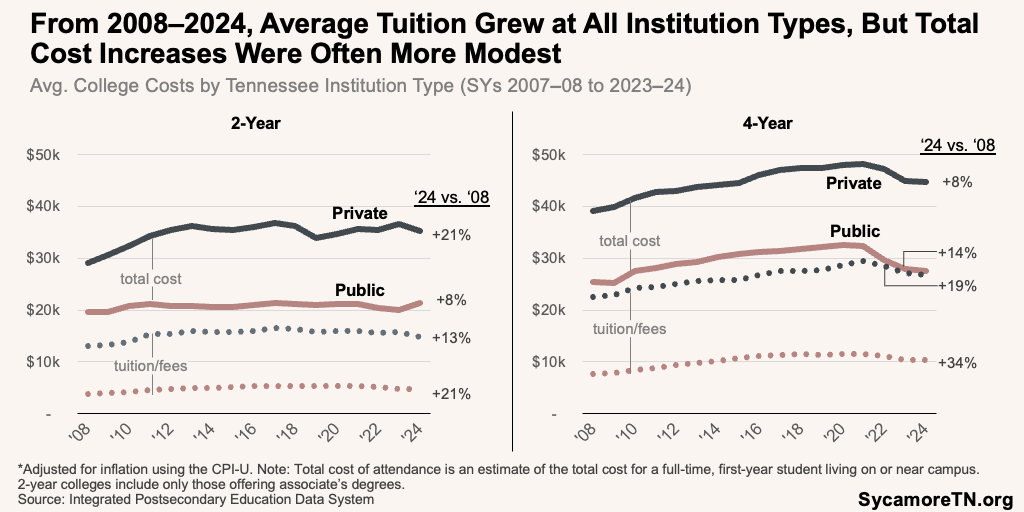

Tennessee’s post-secondary costs and trends vary by institution type and what costs are included (Figure 2). All schools publish tuition, mandatory fees, and a “total cost of attendance.” The latter estimates school and living expenses for a full-time, first-year student living on or near campus. It is also the benchmark for determining financial aid (discussed later). For the 2023-2024 school year (SY), the average estimated total cost of attendance ranged from $21,400 at public two-year colleges to $44,700 at private four-year institutions. (16) Living expenses make up most of those costs at two-year and public four-year institutions, while tuition and fees are the bulk of private four-year costs (Figures 2 and 3). Between SYs 2007–2008 and 2023–2024, average tuition increased at all institution types even after adjusting for inflation, but increases in total cost were more modest at all but private two-year colleges (Figures 2 and 4). (11) (16)

Figure 3

Figure 4

Covering the Post-Secondary Costs in Tennessee

Covering college costs often involves a mix of state, federal, and private resources (Figure 5). Grants, scholarships, and subsidies help cover college costs and do not need repayment. Other sources often involve tapping into the private resources of a student and their families—either now or in the future. Specific sources include:

Grants, Scholarships, and Subsidies

- State and Federal Scholarships and Grants — Tennessee and the federal government offer financial aid for students who meet income, merit, or categorical criteria (e.g., Tennessee HOPE Scholarship, Federal Pell Grants). Because they do not require repayment, these are often referred to as gift aid.

- Private and Institutional Scholarships and Grants — Institutions and private organizations may also award students with gift aid—scholarships and grants that do not need repayment (e.g., local Rotary Club scholarships, university presidential scholarships, donor-endowed scholarships).

- State Subsidies — State taxpayer dollars support public post-secondary institutions. These dollars are not considered direct financial aid to students, but they subsidize the costs of operating public colleges and keep tuition lower for in-state students.

Other Sources

- Personal Resources — Personal resources include family and student income, savings, and contributions from relatives or friends.

- Federal Student Loans — The federal government offers student loans that borrowers must repay.

- Private Loans and Borrowing — Private borrowing for post-secondary education can include private student loans and other forms of credit like home equity loans, retirement account loans, and credit cards.

Determining the mix of resources a student will tap into often begins with the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). (18) The federally administered FAFSA gathers information on the income and expenses of a student’s family. This information generates a “student aid index” (SAI) that gauges financial need based on how much a family can reasonably contribute to a student’s post-secondary expenses. (19) (20) Together, the SAI and the estimated total cost of the student’s chosen school determine the kind and amount of financial aid a student may be eligible for. (19) (20)

Figure 5

Very few students face a college’s full “costs” out of pocket because nearly all students receive state, federal, or institutional aid that does not need repayment (Figure 6). For example, in SY 2021-2022, 97% of full-time, first-time undergraduates at public two-year institutions received grants and scholarships that totaled $6,500 per student, on average. This represented about 36% of the average total cost of attendance at these schools. At private two-year colleges, 79% got an average of $4,500—or 14% of total costs. Among four-year institutions, 97% got an average of $10,300 at public universities—or 39% of total costs—and 92% got an average of $21,900 at private ones—or 52% of total costs. (16)

Figure 6

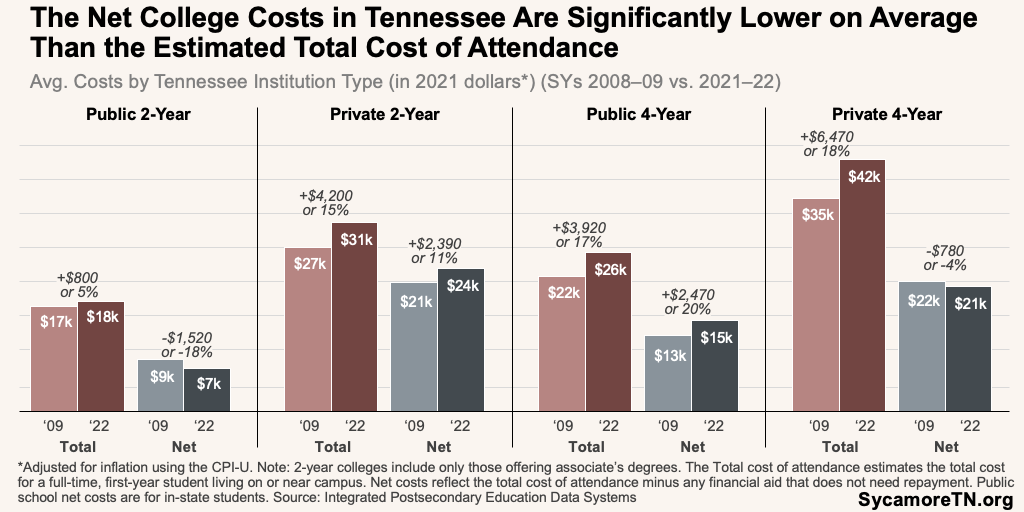

The net costs of college in Tennessee are significantly lower on average than estimated total costs and—for some institution types—have even declined over time (Figure 7). After accounting for student aid, the average net cost to attend a community college was about 61% less than the total cost of attendance for SY 2021-2022. It was 24% less at private two-year colleges and 43% and 50% less at public and private four-year institutions, respectively. Meanwhile, after adjusting for inflation, the net cost of public two-year colleges and private four-year universities declined between the 2008-2009 and 2021-2022 school years. (11) (16)

Figure 7

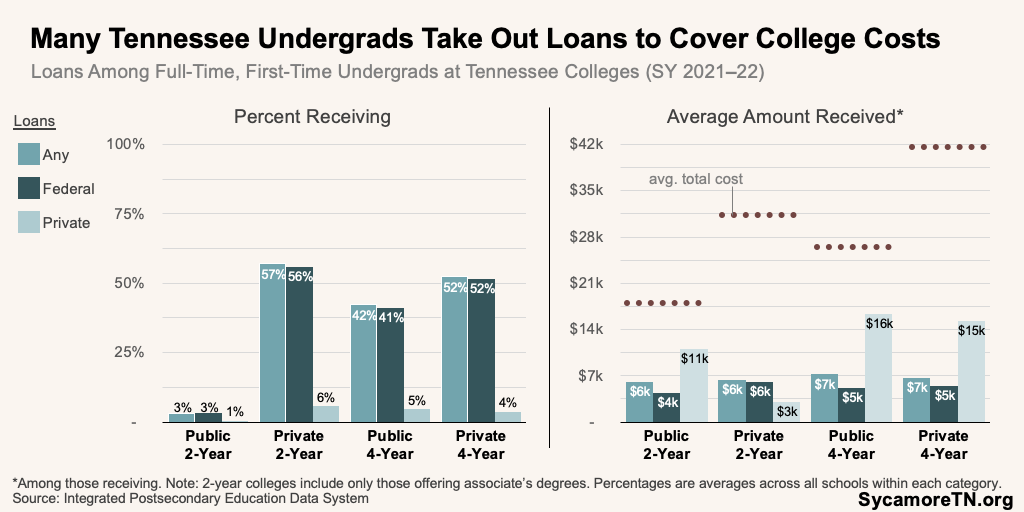

Most undergraduates use personal resources and/or borrow money to cover what grants and scholarships don’t. Tennessee-specific data show that very few students at community colleges took out loans in the 2021-2022 school year, but over half of students at private colleges and universities did (Figure 8). Meanwhile, national survey data for 2024 show that about 74% of families of U.S. undergrads ages 18-24 used parents’ income or savings, 59% used students’, and 16% got money from relatives or friends to cover college costs. (21)

Figure 8

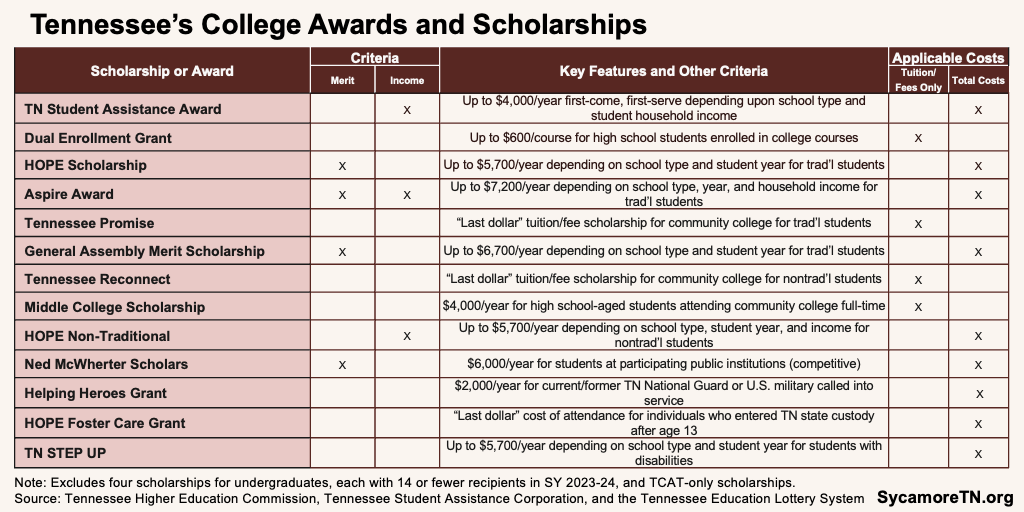

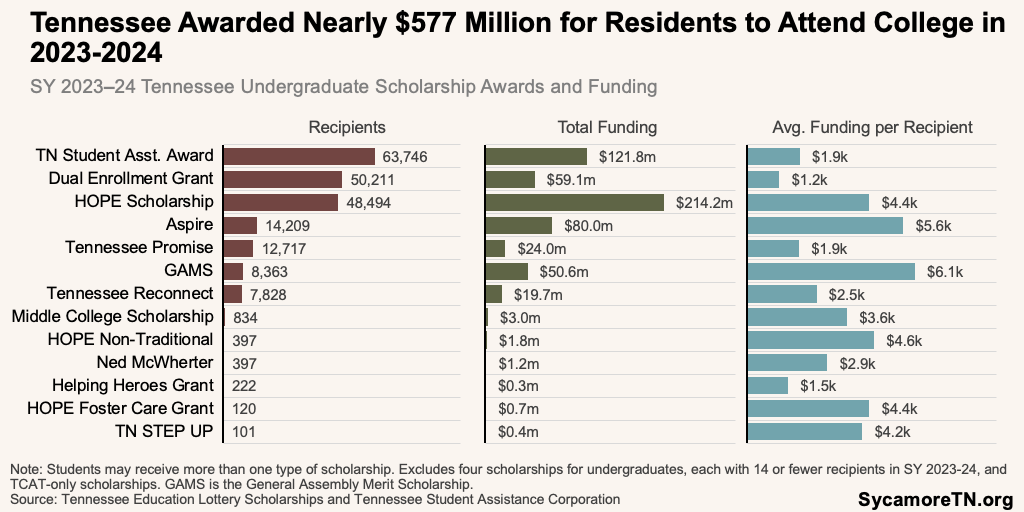

State Grants and Scholarships

Tennessee offers numerous scholarships to help state residents earn a post-secondary degree. (22) For SY 2023-2024, the state awarded nearly $577 million across 16 different scholarships for public and select private two- and four-year colleges and universities in Tennessee (Figure 9 and Table 1). (22) Scholarships are awarded to students who meet merit, income, or categorical criteria (e.g., specific fields of study), attend community college, or take college courses while in high school. (22) The following sections briefly explain each of the state’s largest grants and scholarships. See Appendix Table A1 for additional information on eligibility and requirements.

Table 1

Figure 9

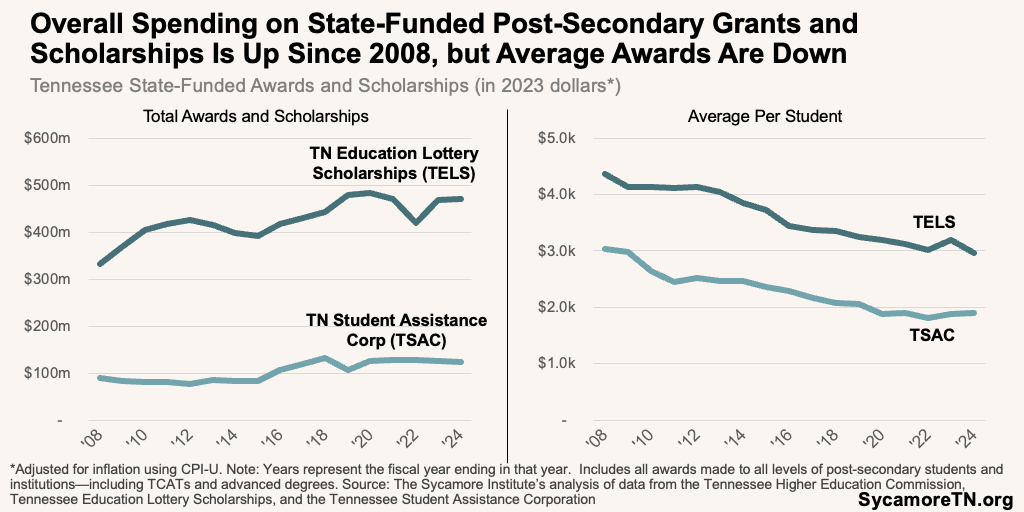

A mix of taxpayer and state lottery dollars finance Tennessee’s state-funded scholarships.(31) (22) Most scholarships offered by the state of Tennessee receive funding from the Tennessee lottery system. However, state General Fund dollars finance a few others—predominantly the Tennessee Student Assistance Award. (31) (22) (36) After adjusting for inflation, overall spending on state-funded post-secondary grants and scholarships is higher than in FY 2008, but the average award amount per recipient is down (Figure 10). (37) (38) (39) (40) (31) (22) (35) (11)

Figure 10

Tennessee Student Assistance Award

The Tennessee Student Assistance Award (TSAA) is need-based and reaches the most Tennessee students—nearly 64,000 in SY 2023-2024. A student’s financial need, as determined by the FAFSA and the cost of the post-secondary institution they attend, determines TSAA eligibility. Students can receive up to $2,000 per year for public colleges and universities and up to $4,000 for private institutions. The Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation board establishes maximum award amounts annually based on available funds. (30) (41)

Tennessee’s Merit-Based Scholarships

Tennessee offers four merit-based scholarships that target recent high school graduates (i.e., traditional first-time students). The HOPE Scholarship requires a 3.0 grade point average (GPA) or a 21 on the ACT exam. The Aspire Award follows the same criteria but provides supplemental funds for students from lower-income families. The General Assembly Merit Scholarship requires a 3.75 GPA or a 29 on the ACT, and the Ned McWherter Scholars Program is a competitive scholarship that requires a 3.75 GPA or 32 ACT score to apply. These scholarships—which range in value from $4,500 for HOPE to $6,000 for Aspire—can be used for costs at any two- or four-year nonprofit colleges accredited in Tennessee. A separate HOPE Non-Traditional Scholarship does not have merit-based criteria but targets lower-income, non-traditional students. (22) (27)

Tennessee Promise and Reconnect

Tennessee’s Promise and Reconnect Scholarships are “last dollar” scholarships that help students cover tuition and mandatory fees for community college. To qualify, students must first tap into any other available merit- and need-based financial aid. In general, Promise and Reconnect fill any remaining gaps for tuition and mandatory fees during the first two years of study at a community college or Tennessee College of Applied Technology (TCAT). Tennessee Promise targets traditional first-time students, while Reconnect is for adults seeking to attend college for the first time or finish their degree. (28) (32) Funds can be used at some four-year universities, but the scholarship is capped at the value of tuition and fees at community colleges.

Post-Secondary Assistance for High Schoolers

State Dual Enrollment Grants cover some or all the costs of earning college credit in high school. The grants help cover the tuition and mandatory fees for up to 10 courses at two- and four-year institutions and TCATs for Tennessee high school students. These courses often help students prepare for college and complete introductory college courses, which can help them graduate earlier and/or decrease their post-secondary costs. (23)

Tennessee Middle College Scholarships provide financial assistance for high school juniors and seniors to earn their associate’s degree while finishing high school. In their last two high school years, eligible students receive $2,000 a semester to enroll at a community college. This can help students enter the workforce sooner or go on to pursue a four-year degree. (25)

Federal Grants

Federal Pell Grants are need-based financial aid that help cover post-secondary costs for students from lower-income families. (42) Pell Grant amounts are based on each student’s financial situation, the cost of attendance at their chosen four-year institution, and full- or part-time enrollment. Awards are capped based on a national annual per-student maximum, currently $7,395 for the 2024-2025 school year. (42) In 2024, over 133,000 Tennessee students received an average grant of just over $5,000. (43)

Private and Institutional Grants and Scholarships

Private businesses, foundations, nonprofits, colleges, and universities themselves award students scholarships and grants to help pay for post-secondary education. (21) For example, about 49% of full-time, first-year students at Tennessee’s public four-year universities and 79% of those at private ones received institutional support in 2021-2022 (Figure 5). (16) Meanwhile, national data show that about 35% of U.S. undergrads received an average of $2,800 per year from private scholarships in 2024. (21)

Federal Student Loans

The federal government guarantees and subsidizes loans to help families borrow for post-secondary costs.(44) Federal loans allow students and families to borrow money for any costs not covered by other financial aid. The federal government often offers loans at lower interest rates than private ones and, in some cases, are directly subsidized to delay the accumulation of interest costs while students are in school.(44) Annual and total limits vary across several types of loans—from $5,500 a year for a Direct Subsidized Loan and up to a school’s cost of attendance for a Direct PLUS Loan. (44)

Figure 11

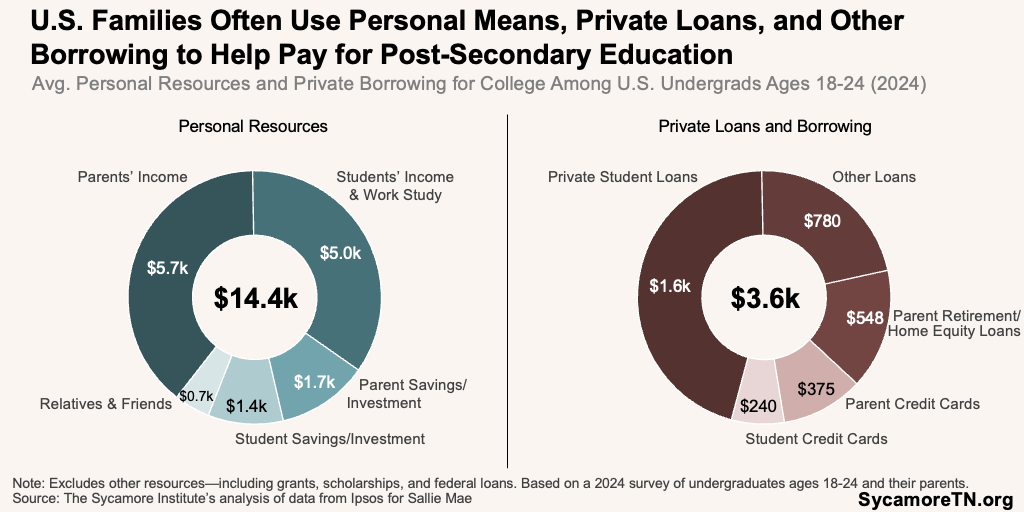

Private Loans and Borrowing

When other resources do not meet a student’s needs, families may turn to private loans or other types of borrowing. Private student loans often have higher interest rates than federal student loans and are not subject to the same federal requirements and regulations. Other types of borrowing may include financing agreements between a company and an employee or between family members, home equity loans, credit cards, retirement account funds, and other lines of credit. (21) (45) In 2024, U.S. families of undergrads relied on about $3,600 in private loans and borrowing, on average, to help finance college—the largest portion of which was from private student loans (Figure 11). (21)

Personal Resources

Student and family income and savings are the largest funding source for the typical American family paying for college. (21) These resources include income and savings from students and parents or money from family and friends (Figure 11). In 2024, the average U.S. family with an 18–24-year-old undergraduate reported contributing about $14,400 in a mix of personal resources, which covered about half of post-secondary costs. (21)

Tax-preferred college savings accounts—529 accounts—are among the personal resources some families use for college. (46) Known as TNStars in Tennessee, anyone can set up and contribute to these accounts, and neither the earnings nor withdrawals are federally taxed if used on tuition and fees, other indirect costs, or to pay off student loans. Other specific benefits and limits of 529 plans vary by state (e.g., TNStars accounts are subject to a total contribution limit of $350,000) and specific account type. However, anyone in any state can open plans in any state or multiple states. Students can benefit from funds from multiple accounts and account owners, and families can transfer accounts to other students. (46) In 2024, 35% of families nationally with an 18–24-year-old undergraduate tapped into a college savings account to pay for students’ college. (21)

Tennessee also offers up to $1,500 in matching funds for lower-income residents who contribute to a TNStars account. The Tennessee Investments Preparing Scholars program provides up to $500 per year and $1,500 total to families under 250% of the poverty level (e.g., $78,000 in 2024 for a family of four) with a TNStars account. The funds provide a four-to-one match. (47)

Many students also work to help cover the costs of post-secondary education. For example, nearly 42% of full-time and 77% of part-time U.S. undergrads worked in 2022. This included 10% and 37%, respectively, who worked more than 35 hours a week. (13) The federal government also subsidizes employment opportunities for students with financial need through work-study programs. The federal work-study program covers up to 70% of wages for qualifying students to work—often at on-campus jobs.

State Subsidies

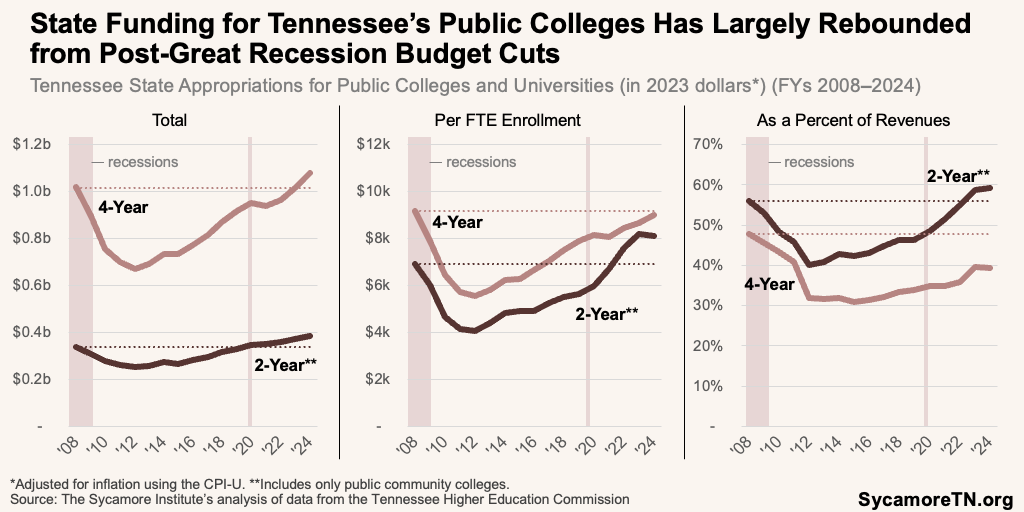

State taxpayer funds for public colleges and universities are not directly reported in how families pay for college, but they subsidize the cost of public schools for in-state students. In FY 2024, for example, the state provided $1.1 billion directly to public four-year schools—or about $8,980 per full-time equivalent (FTE) student. Another $384 million went to community colleges—or $8,120 per FTE student. Relative to tuition and fees, this accounted for 39% of revenues at four-year schools and 59% at community colleges. (31) (48)

State appropriations for public colleges and universities have largely recovered since cuts made in the years after the Great Recession (Figure 12). During the 2007-2009 Great Recession, Tennessee and other states made large higher education funding cuts to help balance state budgets. In FY 2024, however, total funding for the state’s four-year universities was 6% higher than in FY 2008 when that recession hit, even after adjusting for inflation, and funding for community colleges was up 13%. When accounting for enrollment changes, funding was down 2% for four-year institutions and up 18% for community colleges. (11) (48)

Figure 12

In addition to subsidies, the state also has some control over tuition increases at public colleges and universities. Under a 2016 law, the Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC) issues a range for any annual tuition and mandatory fee increases at all public institutions. Institutions can adjust within this range but cannot exceed it. THEC issued its first binding range for SY 2017-2018. (49) Prior to that, each institution’s governing board independently determined annual tuition adjustments.

Issues and Challenges in College Affordability

There are many issues, barriers, and opportunities related to college affordability, both broadly and in Tennessee. The following sections outline some of these issues in broad terms but do not intend to be comprehensive.

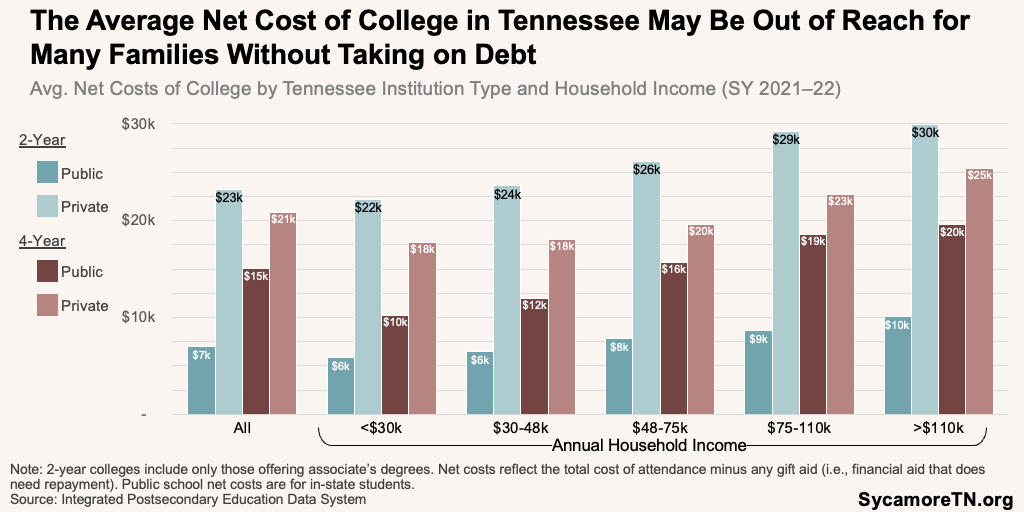

Costs Beyond Financial Aid

Despite available resources, costs remain a barrier to attending and completing college for many students. As discussed above, some costs remain for nearly all students even after accounting for gift aid (Figure 6). Data for SY 2021-2022, for example, show that average net costs for every school type may be out of reach for many students—particularly those from lower income brackets (Figure 13). (16)

Food insecurity among college students is one of the most prominent ways these challenges have presented. Food insecurity occurs when someone has limited or uncertain access to adequate food—often because they cannot afford it. According to surveys, between 20% and 40% of U.S. college students experience food insecurity. (50) (51) In 2022, Tennessee’s public colleges and universities estimated that about 30% of their students were food insecure. Food insecurity can affect both a student’s health and academic success. (52) (53)

Figure 13

Experience with Tennessee Promise highlights this and other challenges students face paying the costs not covered by grants and scholarships. For example, the state comptroller’s 2024 evaluation of Promise found that most of those who struggle to maintain full-time enrollment and GPA requirements cite the challenge of balancing school with the need to work. Promise students were also largely unaware of and surprised that even costs directly related to school were not covered—including books, tools for technical classes, and non-mandatory fees (e.g., lab fees, online course fees). Because of the unexpected expense, students often forgo books. When they do, they usually fall behind. (36) In 2021, the state launched a four-year completion grant pilot program to help lower-income students cover some of these costs. Most grants were used for food and transportation costs in the program’s first two years. (54)

Student Debt

Student loans can enable access to education and increased earnings, but they may come with trade-offs. For example, when repayments strain available resources, student loan repayors must balance those payments with spending on life’s other necessities. Repayments may delay investments that can build long-term wealth (e.g., buying a house) or help prepare for the future (e.g., retirement savings). In the worst-case scenario, defaulting on a student loan can damage credit, resulting in negative consequences. (55) (56) (57) (58)

Most studies generally agree that undergraduate degrees and debts taken on to pay for them usually have a positive return, but specific pathways and circumstances may not. (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) A late 2023 poll showed 47% of Americans thought college wasn’t worth it if it involved taking out loans. (59) However, available evidence suggests the value and risks of borrowing for college are nuanced. For example:

- Fields of Study — Some fields are more likely to pay off than others.(60) (31) (61) (62) In one analysis, for example, engineering, computer science, nursing, and economics degrees generated the highest returns for graduates. (6)

- Graduate School Loans — The return on investment (ROI) is most uncertain for graduate school loans, which comprise about half of all federal student loan debt.(63) (64) (65) (66) (58)

- Timing — The timing of the ROI is important for paying off student loans. Some careers may pay less early on but ultimately pay off over a lifetime. This can make it more difficult for graduates in those fields to make student loan payments right out of college.(60)

- Completion — Completion is important. People who take out loans to begin school but never earn a degree have one of the highest risks for default.(67) (68) (69) (70)

- For-Profit Institutions — Graduates of certain institution types have disproportionately high default rates—particularly for-profit institutions.(71) (63) (68)

Sticker Shock

Perceptions of college costs (i.e., sticker shock)—and not actual costs—influence if and where students attend college. As explained above, very few students ever face the published costs of attendance—which many refer to as the “sticker price”—because nearly all students receive financial aid that does not need repayment. However, studies suggest that sticker prices influence students’ decisions about if and where to go to college—especially among lower-income students—and greater transparency and individualized information about costs could address these effects. (72) (12) (73)

Getting and Retaining Financial Aid

Some students face challenges in getting and retaining available financial aid. Tennessee has the best FAFSA completion rate in the country. (74) Even so, students from the class of 2023 could have accessed as much as $53 million more in Pell Grants if everyone had completed it. (75) Additionally, about half of those who apply for Promise lose their eligibility before they enroll because they miss a mandatory meeting, don’t complete the community service requirements, or file their FAFSA late. (36) Many of those who do secure aid fail to maintain eligibility requirements (Appendix Table A1). For example, about 40% of HOPE recipients who began college in Fall 2022 had lost the scholarship by Fall 2023. (22)

In addition to the reasons cited above, students may not access or retain grants and scholarships because of complexity and confusion. For example, the comptroller’s 2024 evaluation of Promise found that students and their families were often confused because each state program (e.g., Promise, HOPE) has different requirements. They were also frustrated with the need for multiple applications, and some felt that the requirements for full-time enrollment were hard to juggle with competing demands for their time, like work and family. (36)

State Statutory Issues

Statutory maximums limit several of Tennessee’s scholarships, which haven’t always kept up with inflation. Examples include:

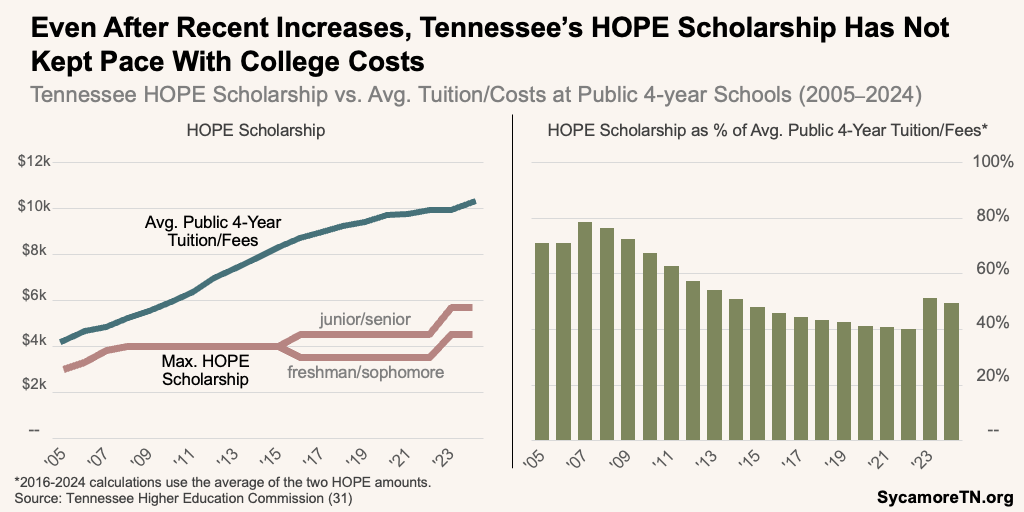

- HOPE Scholarship — Under state law, the traditional HOPE Scholarship provides up to $4,500 to freshmen/sophomores and $5,700 to juniors/seniors for four-year universities or $3,200 to students at two-year schools. When the HOPE Scholarship first launched, it covered about 70% of average tuition and fees at public four-year schools. Even after an increase in the maximum award amounts in 2022, the HOPE Scholarship covered about half of the average tuition and fees in 2023-2024 (Figure 14). (31)(22)

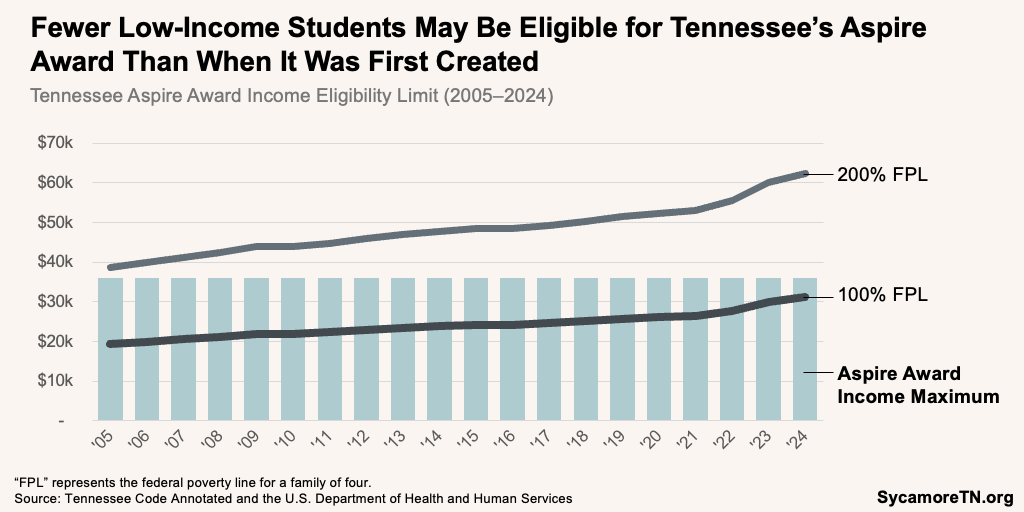

- Aspire Award — The Aspire Award is limited to students with an annual adjusted gross income of no more than $36,000, an amount set in state law in 2005.(76) Over time, the value of this limit has diminished with inflation, reducing the share of students potentially eligible for the award. (76) (77) (9) For example, the Aspire income limit represented nearly 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) for a family of four in 2005 (Figure 15). In 2024, the same limit is closer to 100% of FPL. (77)

Figure 14

Figure 15

Private Scholarship Displacement

Schools can reduce the financial aid they provide to students who receive outside private scholarships. (78) Private scholarships can count towards a student’s total financial aid calculation, which cannot exceed a school’s total cost of attendance. (19) (79) (78) (80) After schools learn of a student’s private scholarships, they may reduce the financial aid they’ve already offered by an equivalent amount—a practice known as scholarship displacement. (79) (78)

Scholarship displacement can come with trade-offs for students, colleges, and the private entities that award scholarships. When institutions reduce gift aid, scholarship displacement frees up those dollars for other students with unmet needs. Conversely, returning the scholarship could do the same for the awarding entity, or reducing other sources of aid first—like federal loans—could lower a student’s debt burden. Meanwhile, students often expect their private scholarships to add to rather than displace the aid a school has already offered, so the practice often surprises both students and the private grantor. Finally, private entities often award scholarships to help students they choose based on their merit or purpose, and scholarship displacement has reportedly left many feeling like their dollars are supporting a university’s endowment or another student, which may or may not represent their stated goal or mission. (78) (79) (80) (81) (82)

State Grant Incentives

Although they have expanded access to post-secondary education, Tennessee’s investments in community college may incentivize choices that make it harder for some to earn a degree. For example, Promise may incentivize some students seeking a bachelor’s degree to begin their studies at a two-year school. (83) (84) Indeed, community college students receiving Promise are more likely to transfer to four-year universities than similar non-Promise peers. (36) However, research shows that students who transfer from community colleges struggle to finish and are less likely to earn their bachelor’s than those who begin at four-year schools. (85) (86) (87) (88) Only 48% of Tennessee students who began community college in 2015 and transferred to a four-year school earned their bachelor’s degree within six years. (89) Tennessee has worked to reduce one known barrier—creating pathways that guarantee community college credits will transfer to four-year universities. (90)

“Total Cost of Attendance”

Federal requirements for “total cost of attendance” and financial aid may affect how schools estimate costs and contribute to students’ sticker shock, confusion, or unexpected costs. Under federal rules, a student’s financial aid package—which includes any gift aid and some federal student loans—cannot exceed the total cost of attendance estimated by the school they attend. (19) (44) (44) Meanwhile, the loan default rates of a school’s graduates can affect an institution’s eligibility for Pell Grants. (91) As a result, a school may overestimate costs to ensure their students have enough funds to cover any expenses they encounter. In contrast, others may take a more conservative approach to keep people from taking out student loans they cannot repay. These practices may contribute to sticker shock or shortfalls when students encounter costs that exceed these estimates. (12) (92)

External Cost Pressures

Outside pressures—like those in the housing market—can increase student costs and create challenges for colleges and universities. Housing constitutes about a quarter of Tennessee’s average estimated cost of attending a public college or university (Figure 3). In 2020, only 18% of U.S. college students lived on campus, and 48% reported that the options in the local housing market near their university were unaffordable. (93) (94) Indeed, housing prices have increased rapidly in recent years in parts of Tennessee as the home supply has failed to keep up with growing demand. This has been connected to many students opting for on-campus housing, leading to housing shortages for universities statewide. These schools have reportedly leased hotels, apartment complexes, and nearby residences to fill the housing shortages faced by their students. (95) (96) (97) (98)

Parting Words

Post-secondary education can provide opportunities for students to climb the socioeconomic ladder, and Tennessee has put significant effort over the last decade into expanding these opportunities. As a result, Tennessee students have many resources available to help fund their education, but those resources can still fall short of covering students’ total needs. This report sheds light on students’ true costs and complexities and the risks and trade-offs some options may involve.

*This report was updated on Nov. 20, 2024 to correct applicable costs for the Helping Heroes and HOPE Foster Care Grants, clarify that the McWherter Scholarship is competitive, and correct a typo in Figure 2.

References

Click to Open/Close

References

- Gallup, Inc. Education for What? Lumina Foundation. August 30, 2023. https://www.luminafoundation.org/resource/education-for-what/

- Strohl, Jeff, Gulish, Artem and Morris, Catherine. The Future of Good Jobs: Projections Through 2031. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce and JPMorganChase. 2024. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/cew-the_future_of_good_jobs-fr.pdf

- Denning, David. Why Do Wages Grow Faster for Educated Workers? Harvard University and NBER. June 2023. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60832ecef615231cedd30911/t/648782a74c77dd494b02c789/1686602408024/Deming_OJL_June2023.pdf

- The HEA Group. Ensuring a Living Wage Through Higher Education. February 20, 2024. https://www.theheagroup.com/blog/ensuring-a-living-wage-through-higher-education

- Carnevale, Anthony P., et al. Learning and Earning by Degrees. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. 2024. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/CEW-attainment-gains-full_report.pdf

- Cooper, Preston. White Paper Higher Education, ROI Does College Pay Off? A Comprehensive Return On Investment Analysis. The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. May 8, 2024. https://freopp.org/whitepapers/does-college-pay-off-a-comprehensive-return-on-investment-analysis/

- Barrow, Lisa. Is College a Worthwhile Investment? Examining the Benefits and Challenges. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. February 2024. https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-insights/2024/policy-brief-is-college-a-worthwhile-investment

- Vandenbroucke, Guillaume. The Return on Investing in a College Education. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. March 23, 2023. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/2023/mar/return-investing-college-education

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2010-2023 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. September 2023. Available via http://data.census.gov.

- Murray, Charles. Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010. New York : Crown Forum/Random House, 2012.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index: CPI-U. Accessed from https://www.bls.gov/.

- Unglesbee, Ben. Sticker Shock: A Look at the Complicated World of Tuition Pricing. Higher Ed Drive. July 1, 2024. https://www.highereddive.com/news/college-tuition-sticker-price-discounting-revenue/721847/

- National Center for Education Statistics. Table 503.20. Percentage of College Students 16 to 24 Years Old Who Were Employed, By Attendance Status, Hours Worked per Week, and Control and Level of Institution: Selected Years, October 1970 Through 2022. 2023 Digest of Education Statistics. June 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_503.20.asp?current=yes

- Gallup and Lumina Foundation. State of Higher Education 2024 Report. 2024. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/644939/state-of-higher-education.aspx#ite-644921

- EDGE Research and HCM Strategists. Exploring the Exodus from Higher Education. May 2022. https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/HCM-EDGE-Research.pdf.

- Institute of Education Sciences. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Accessed in October and November 2024 from https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data.

- Tennesssee Higher Education Commission. 2024-25 Cost of Attendance Estimates, In-State Undergraduate Students. Provided to the Sycamore Institute on October 29, 2024.

- Monagle, Laura L. Planning and Paying for College: Federal Government Resources. Congressional Research Service. Congressional Research Service. April 19, 2024. Accessed from https://crsreports.congress.gov/.

- Federal Student Aid. How Financial Aid Is Calculated. U.S. Department of Education. https://studentaid.gov/complete-aid-process/how-calculated#need-based.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Learning How FAFSA Works. Consumer Finance Protection Bureau. August 11, 2022. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/consumer-tools/educator-tools/youth-financial-education/teach/activities/learning-how-fafsa-works/.

- Ipsos. How America Pays for College 2024. Sallie Mae. 2024. https://www.salliemae.com/about/leading-research/how-america-pays-for-college/

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission. 2020-2024 TELS Year-End Reports. 2020-2024. Accessed from https://www.tn.gov/thec/research/tn-hope-scholarship-program.html.

- College For TN. Dual Enrollment Grant. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/dualenrollment/

- —. Helping Heroes Grant. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/helping-heroes-grant/

- —. Middle College Scholarship. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/middle-college/

- —. Tennessee HOPE Foster Child Tuition Grant. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/tennessee-hope-foster-child-tuition-grant/

- —. Tennessee HOPE Scholarship – Nontraditional. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/tennessee-hope-scholarship-nontraditional/

- —. Tennessee Promise Scholarship. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Commission. https://www.collegefortn.org/tennessee-promise-scholarship/

- —. Tennessee STEP UP Scholarship. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/tennessee-step-up-scholarship/

- —. Tennessee Student Assistance Award. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/tennessee-financial-aid/tennessee-student-assistance-award/

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission. 2024 Higher Education Fact Book. 2024. https://www.tn.gov/thec/research/fact-book.html

- Tennessee Reconnect. Tennessee Reconnect Grant. https://tnreconnect.gov/Tennessee-Reconnect-Grant

- College For TN. Ned McWherter Scholars Program. Tennessee Higher Education Commission and Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. https://www.collegefortn.org/ned-mcwherter-scholars-program/

- State of Tennessee. Chapter 1640-01-19 Tennessee Education Lottery Scholarship Program. Rules of the Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. November 2023. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/rules/1640/1640-01-19.20231105.pdf.

- Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. 2020-2024 TSAC Grants and Scholarships Year-End Reports. Tennessee Higher Education Commission. 2020-2024. Accessed from https://www.tn.gov/thec/research/tn-hope-scholarship-program.html.

- Brown, Erin and Quittmeyer, Robert. Tennessee Promise Evaluation. Tennessee Comptroller, Office of Research and Evaluation. January 2024. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/orea/advanced-search/2024/TNPromise2024Fullreport.pdf

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission. 2008-2009 Tennessee Higher Education Fact Book. 2009. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED512269.pdf

- —. 2009-2010 Tennessee Higher Education Fact Book. 2010. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED512238.pdf

- —. 2012-2013 Tennessee Higher Education Fact Book. 2013. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED560718.pdf

- —. 2012-2023 Tennessee Higher Education Fact Books. 2011-2023. Available from https://www.tn.gov/thec/research/fact-book.html.

- Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation. TN Comp Rules and Regs 1640-01-01-.03. Rules & Regulations of the State of Tennessee. September 24, 2024. https://regulations.justia.com/states/tennessee/title-1640/chapter-1640-01-01/section-1640-01-01-03/

- Federal Student Aid. Federal Pell Grants. U.S. Department of Education. https://studentaid.gov/understand-aid/types/grants/pell

- Hanson, Melanie. Pell Grant Statistics. Education Data Initiative. January 28, 2024. https://educationdata.org/pell-grant-statistics

- Federal Student Aid. Federal Student Loans. U.S. Department of Education. https://studentaid.gov/understand-aid/types/loans

- Student Borrower Protection Center. Private Student Lending. April 2020. https://protectborrowers.org/private-student-loans/

- Tennessee Financial Literacy Commission. 529 Plans. Tennessee Department of Treasury. https://tnflc.everfi-next.net/student/dashboard/login/investing-in-your-future/1878?locale=en#529-plans

- Tennessee Department of Treasury. TIPS Program. https://treasury.tn.gov/Services/For-All-Tennesseans/College-Savings/TIPS-Program

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission. Work Program for FYs 1992-1993 to 2024-2025. Provided to Sycamore in October 2024.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 869 (2016). April 19, 2016. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/109/pub/pc0869.pdf

- The Hope Center for Student Basic Needs. Preview: 2023-24 Student Basic Needs Survey Report. Temple University. September 2024. https://hope.temple.edu/research/hope-center-basic-needs-survey/preview-2023-24-student-basic-needs-survey

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Estimated Eligibility and Receipt among Food Insecure College Students. June 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-24-107074.pdf

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission. Food Insecurity in Tennessee Higher Education. 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/learn-about/taskforces/food_insecurity/Food%20Insecurity%20Report_For%20Release_12142023.pdf

- Afyouni, Amal. Food Insecurity and Higher Education: A Review of Literature and of Resources. Tennessee Higher Education Commission. 2023. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/learn-about/taskforces/food_insecurity/Food%20Insecurity%20Literature%20Review%20Final%20Draft_11142023.pdf

- Tennessee Higher Education Commission. Tennessee Completion Grants: 2023 Annual Report. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/thec/bureau/research/completion-grants-report/Completion%20Grants_2023_FINAL.pdf

- Wielk, Emily and Stein, Tristan. Measuring the Return on Investment of Higher Education: Breaking Down the Complexity. Bipartisan Policy Center. April 4, 2024. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/measuring-the-return-on-investment-of-higher-education-breaking-down-the-complexity/

- Underwood, Emily. The Knotty Economics of Student Loan Debt. Knowable Magazine. September 9, 2023. https://knowablemagazine.org/content/article/society/2023/knotty-economics-student-loan-debt

- U.S. Department of Education. Student Loan Delinquency and Default. https://studentaid.gov/manage-loans/default

- Meyer, Katharine. The Causes and Consequences of Graduate School Debt. Brookings. October 4, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-causes-and-consequences-of-graduate-school-debt/

- Fry, Richard, Braga, Dana and Parker, Kim. Is College Worth It? Pew Research Center. May 23, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/05/23/is-college-worth-it-2/

- Broady, Kristen and Hershbein, Brad. Major Decisions: What Graduates Earn Over Their Lifetimes. The Hamilton Project. October 8, 2020. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/post/major-decisions-what-graduates-earn-over-their-lifetimes/

- The Hamilton Project. Career Earnings by College Major. The Brookings Institute. October 8, 2020. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/data/career-earnings-by-college-major/

- The Economist. Gary Becker’s Concept of Human Capital. August 4, 2017. https://www.economist.com/schools-brief/2017/08/04/gary-beckers-concept-of-human-capital

- The HEA Group. Think Hard: Your Graduate School’s Sector Matters. December 6, 2023. https://www.theheagroup.com/blog/think-hard-graduate-school

- Gulish, Artem, et al. Graduate Degrees: Risky and Unequal Paths to the Top. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. 2024. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/cew-graduate_degrees-fr.pdf

- Itzkowitz, Michael. Some Graduate Schools Never Pay Off. The HEA Group. August 1, 2023. https://www.theheagroup.com/blog/grad-schools-debt

- Camp, Emma. The Real Student Loan Crisis Isn’t From Undergraduate Degrees. Reason. March 2024. https://reason.com/2024/02/06/the-real-student-loan-crisis/

- Takyi-Laryea, Ama and Oliff, Phillip. Who Experiences Default? Pew. March 1, 2024. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2024/who-experiences-default

- Looney, Adam and Yannelis, Constantine. What Went Wrong With Federal Student Loans? Brookings. September 17, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-went-wrong-with-federal-student-loans/

- Siegel Bernard, Tara. They Got Debt But Not the Degree. The New York Times. June 1, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/01/your-money/student-loan-debt-degree.html

- Itzkowitz , Michael. The College Completion Crisis Fuels the Student Debt Crisis. The HEA Group. January 31, 2024. https://www.theheagroup.com/blog/college-completion-crisis-fuels-student-debt-crisis

- Looney, Adam and Yannelis, Constantine. The Consequences of Student Loan Credit Expansions: Evidence from Three Decades of Default Cycles. October 2019. https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/faculty/constantine-yannelis/research/creditsupply.pdf

- Levine, Phillip B., Ma, Jennifer and Russell, Lauren C. Do College Applicants Respond to Changes in Sticker Prices Even When They Don’t Matter? Education Finance and Policy (2023) 18(3): 365–394. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00372

- Carrns, Ann. That Giant College ‘Sticker’ Price Isn’t What Most Students Pay. The New York Times. April 12, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/12/your-money/college-tuition-cost-.html

- Greene, Jessie. Tennessee Higher Education Commission Announces 2024 FAFSA Champions. Tennessee Higher Education Commission. August 29, 2024. https://www.tn.gov/thec/news/2024/8/29/fafsa-champions/

- Woodhouse, Louisa and DeBaun, Bill. NCAN Report: In 2023, High School Seniors Left Over $4 Billion on the Table in Pell Grants. National College Attainment Network. January 11, 2024. https://www.ncan.org/news/662266/NCAN-Report-In-2023-High-School-Seniors-Left-Over-4-Billion-on-the-Table-in-Pell-Grants.htm

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 49-4-915. Accessed via Lexis.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References. https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references.

- Marcus, John. ‘August Surprise’: That College Scholarship You Earned Might Not Count. The Hechinger Report. August 2, 2023. https://hechingerreport.org/august-surprise-that-college-scholarship-you-earned-might-not-count/

- Farrington, Robert. How to Avoid Scholarship Displacement With Private Scholarships. Forbes. August 23, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertfarrington/2023/08/29/how-to-avoid-scholarship-displacement-with-private-scholarships/

- Onwenu, Justin. The Catch-22 of Applying for Private Scholarships. The New York Times. November 7, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/07/opinion/private-scholarship-displacement.html

- Hughes, Stephanie. Getting Private Scholarships for College Doesn’t Necessarily Mean a Reduced Bill. Marketplace. August 2, 2023. https://www.marketplace.org/2023/08/02/college-tuition-scholarship-displacement/

- Coker, Ph.D., Crystal and Glynn, Ph.D., Jennifer. Making College Affordable. Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. November 2017. https://www.jkcf.org/research/making-college-affordable-providing-low-income-students-with-the-knowledge-and-resources-needed-to-pay-for-college/

- Nguyen, Hieu. Free College? Assessing Enrollment Responses to the Tennessee Promise Program. Labour Economics, 66. July 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101882

- Carruthers, Celeste and Fox, William. Aid for All: College Coaching, Financial Aid, and Post-Secondary Persistence in Tennessee. Economics of Education Review, 50. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.06.001

- Delaney, Taylor. 2-Year or Not 2-Year? The Impact of Starting at Community College on Bachelor’s Degree Attainment. Research in Higher Education, 65. July 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-024-09805-7

- Pretlow, Joshua, Cameron, Margaux and Jackson, Deonte. Community College Entrance and Bachelor’s Degree Attainment: A Replication and Update . Community College Review, 50(3). April 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/00915521221087281

- Scheld, Jessica. The Path to a Bachelor’s Degree: The Effect of Starting at a Community College. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 23(8). 2023. https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v23i8.6074.

- Velasco, Tatiana, et al. Tracking Transfer: Community College and Four-Year Institutional Effectiveness in Broadening Bachelor’s Degree Attainment. Community College Research Center, Columbia University. February 2024. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/Tracking-Transfer-Community-College-and-Four-Year-Institutional-Effectiveness-in-Broadening-Bachelors-Degree-Attainment.html

- Community College Research Center. Tracking Transfer: State-by-State Outcomes. Columbia University. February 2024. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/tracking-transfer-state-outcomes.html

- Tennessee Board of Regents. Tennessee Transfer Pathways. https://www.tntransferpathway.org/transfer-admission-guarantee

- Hegji, Alexandra and Bryan, Sylvia L. Cohort Default Rates and HEA Title IV Eligibility: Background and Analysis . Congressional Research Service. December 12, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47874

- Kelchen, Robert, Hosch, Braden J. and Goldrick-Rab, Sara. The Costs of College Attendance: Examining Variation and Consistency in Institutional Living Cost Allowances. Taylor & Francis Online. March 9, 2017. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00221546.2016.1272092

- Butler, Natalie and Torres, Francis. Housing Insecurity and Homelessness Among College Students. Bipartisan Policy Center. August 15, 2023. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/housing-insecurity-and-homelessness-among-college-students/

- National League of Cities. Housing for Post-Secondary Students. National League of Cities. January 17, 2024. https://www.nlc.org/article/2024/01/17/housing-for-post-secondary-students/

- Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. TSU’s Intensified Scholarship Program Contributed to Housing Shortage. February 22, 2023. https://comptroller.tn.gov/news/2023/2/22/tsu-s-intensified-scholarship-program-contributed-to-housing-shortage.html

- Sims, Jaylan. TSU Students, Alumni Hopeful New Complex Begins to Solve Housing Woes. Nashville Banner. [May 16, 2024. https://nashvillebanner.com/2024/05/16/tsu-housing-crisis-relief/

- Wright, Shelby. UT Hosts Off-Campus Housing Fair in Wake of Housing Crisis. The University of Tennessee Daily Beacon. September 26, 2023. https://www.utdailybeacon.com/campus_news/dining_and_housing/ut-hosts-off-campus-housing-fair-in-wake-of-housing-crisis/article_0dbb8982-5c89-11ee-8872-ef004578ea41.html

- Morton, Zoe. Campus Housing: Shortage of 1,000 Beds for Fall ’24. University Echo. April 3, 2024. https://www.theutcecho.com/news/campus-housing-shortage-of-1-000-beds-for-fall-24/article_725090ca-f074-11ee-8bcf-37fdab7c1e01.html