Key Takeaways

- Compared to the FY 2025 enacted budget, Gov. Lee’s budget reflects January’s special session spending and proposes new spending for FYs 2025-2026—funded mainly by previously unallocated recurring revenues, a large FY 2024 surplus, and new FY 2026 revenue growth.

- Spending in the governor’s FY 2026 recommendation from all revenue sources is 2% (or $1.1 billion) lower than FY 2025 estimates. Spending from state revenues is 9% (or $2.4 billion) higher.

- The largest recurring increases include recommended growth related to TennCare, state personnel-related costs, and school funding formula growth.

- Lee proposes a $1.0 billion General Fund transfer to the Highway Fund, as transportation revenues fail to keep up with road construction costs.

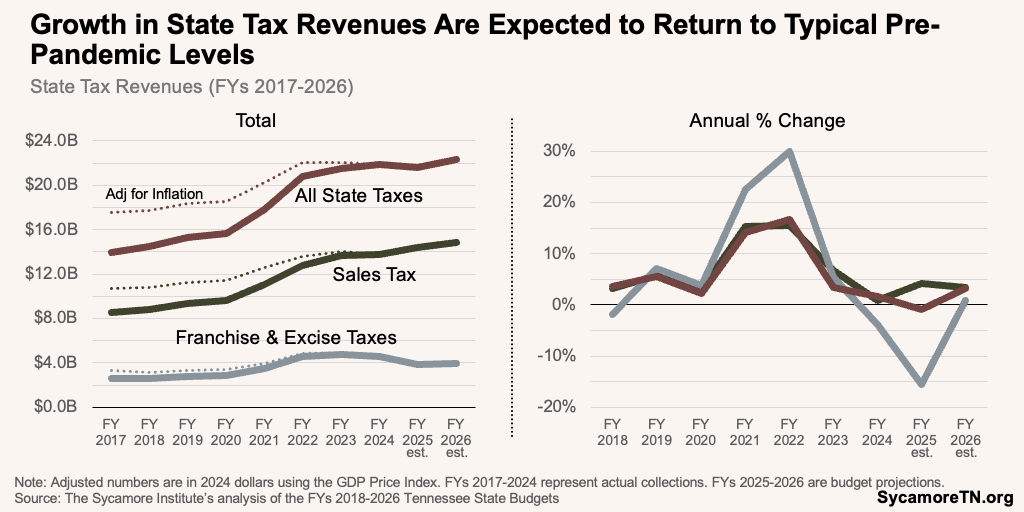

- The Budget expects growth in total state tax collections that is more typical of the state’s experience before the ups and downs that came with the pandemic and recent tax cuts.

- The state’s main rainy day reserve would total $2.2 billion in FY 2026 and cover about 31 days of General Fund operations—about 6 days more than before the Great Recession.

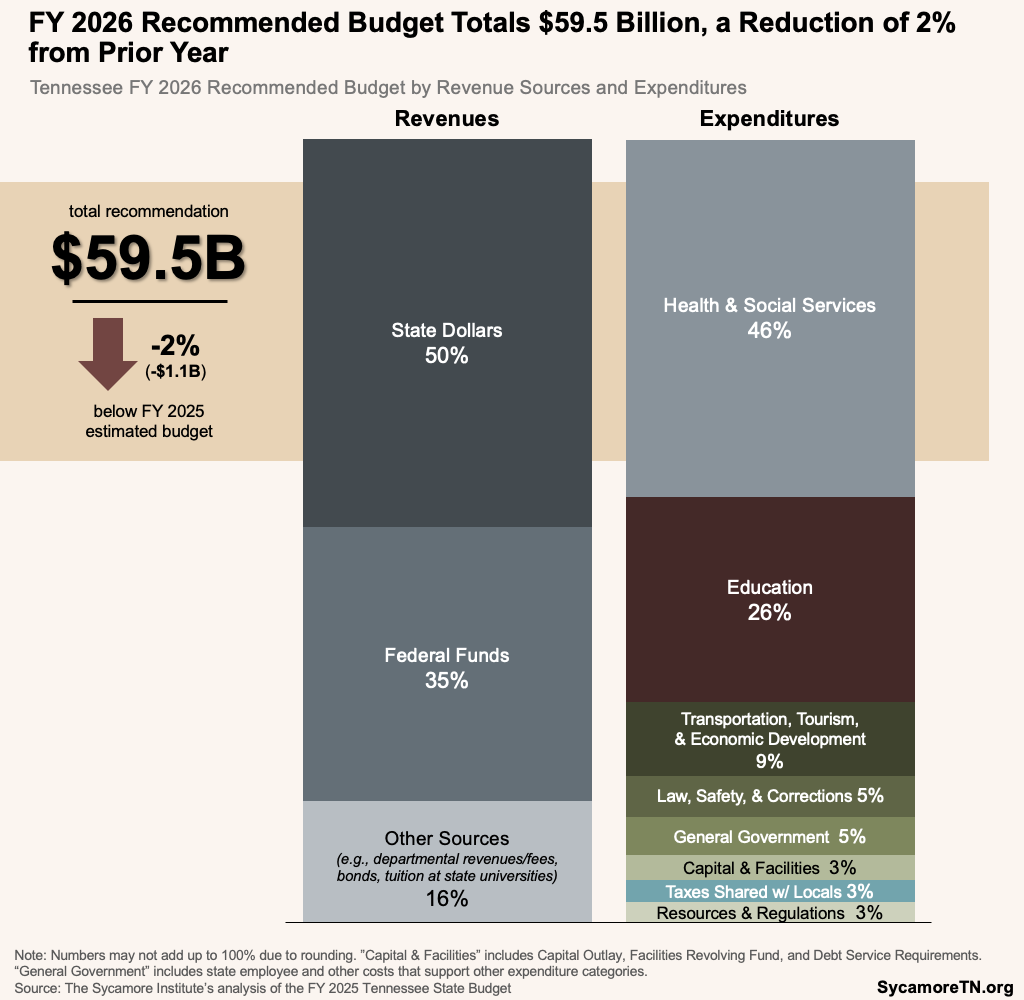

On February 10, 2025, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee released his $59.5 billion recommendation for the state’s FY 2026 state budget along with recommended changes for FY 2025. (1) Budgets reflect policymakers’ goals, the public goods and services intended to help meet those goals, and a detailed plan to finance them. It is now the legislature’s job to consider and act on this recommendation.

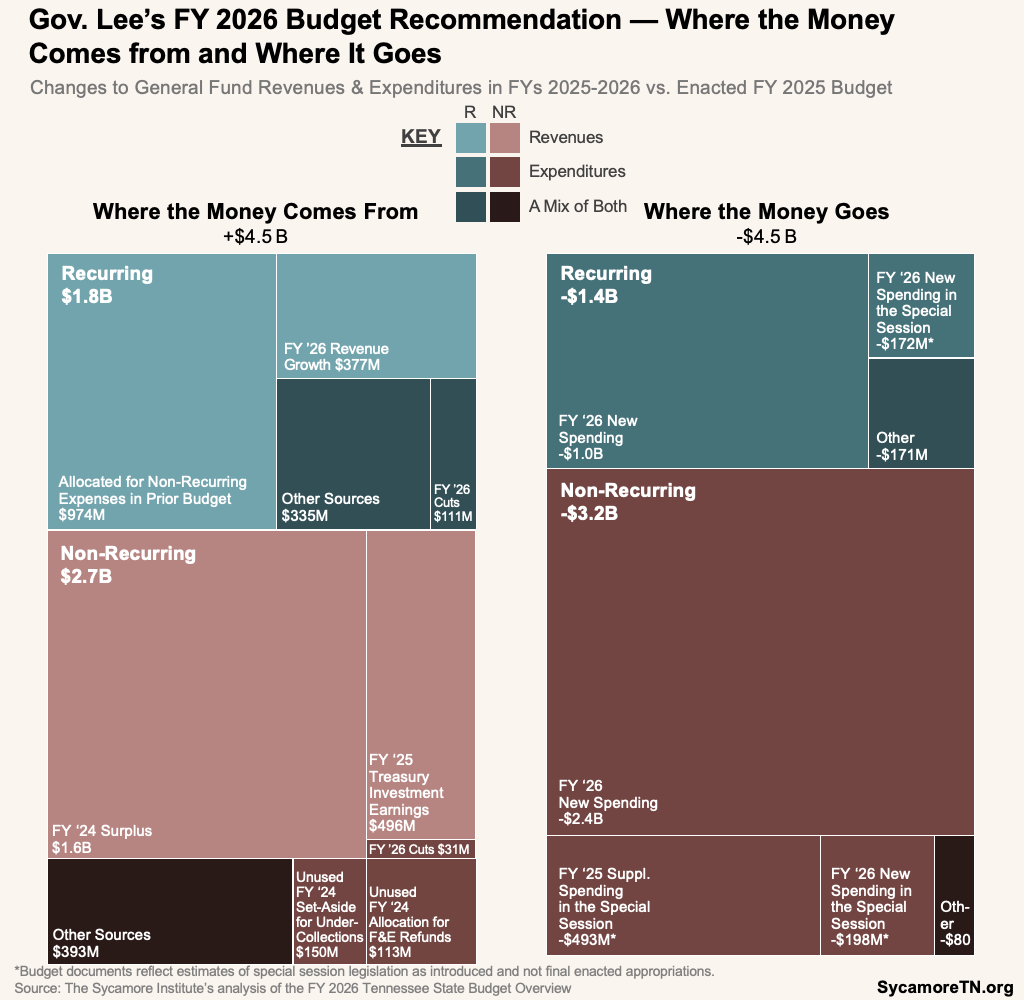

Figure 1

General Fund Overview

Compared to the FY 2025 enacted budget, Gov. Lee’s budget includes January’s special session spending and proposes new spending for FYs 2025-2026—funded mainly by previously unallocated recurring revenues, a large FY 2024 surplus, and new FY 2026 revenue growth. This report discusses many of the spending items throughout. The budget is balanced with (Figure 1):

- $1.6 billion from the FY 2024 end-of-year surplus (discussed below).

- $974 million in recurring money used for non-recurring purposes in FY 2025 (discussed below).

- $496 million from earnings on the Treasurer’s investment of state funds.

- $377 million in new FY 2026 tax growth (discussed later).

- $142 million from proposed spending reductions—including $111 million recurring and $31 million non-recurring.

- $150 million that was set aside but not needed in FY 2024 in case tax collections did not meet estimates.

- $113 million in unused funds allocated for franchise tax refunds.

- $727 million in other revenues and balances—including $335 million recurring and $393 million non-recurring.

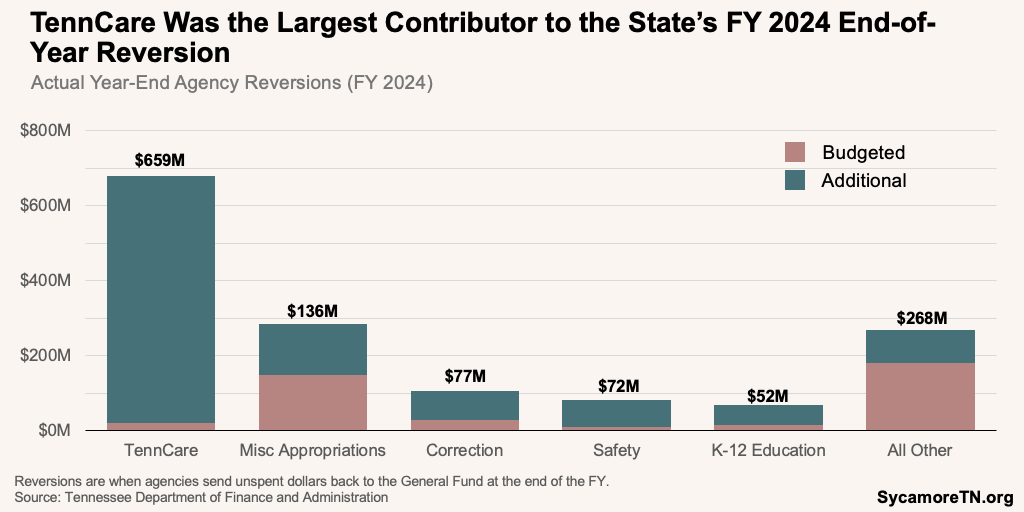

The state ended FY 2024 with another large $1.6 billion surplus—largely from unspent program “reversions” (Figure 2). State agencies reverted about $1.4 billion in unspent money to the General Fund—or $1.1 billion more than expected. The surplus also includes $131 million in FY 2024 unbudgeted earnings from the treasurers’ investment of state funds and $117 million in FY 2024 General Fund overcollections (i.e., actual tax collections above those expected under the mid-year revised projection).

Figure 2

When agencies send unspent dollars back to the General Fund at the end of the fiscal year, these are known as reversions. These unspent dollars can come from program and personnel underspending, delayed start-up of recurring initiatives, over-collection of departmental revenues like fees and licenses, and program reserves. Agency reversions have been unusually high in recent years (Figure 3). Much of the savings came from TennCare, where the availability of more federal dollars under a COVID-19-related enhanced match rate freed up state funds (Figure 4). (5) That enhanced match rate was fully phased out on December 31, 2023. (6)

Figure 3

Figure 4

In addition to the surplus, the FY 2026 Budget also draws on $974 million in recurring revenue that the prior budget allocated for non-recurring purposes. The last several budgets used new recurring revenues for one-time purposes for fear that revenue collections could slow or decline. By not tying these dollars up for long-term commitments, they remain unallocated for future years. The recommendation continues this practice into FY 2026 by proposing to use about $411 million in expected recurring revenues for one-time purposes.

Special Session

The recommendation accounts for $863 million in new estimated General Fund spending from January’s special session on K-12 education, disaster recovery, and immigration enforcement. This includes $172 million recurring and $692 million non-recurring. The budget reflects an estimate and not actual appropriations due to the timing of the session and the preparation of budget documents. The new approved spending was about $5 million more. (13) The administration and/or legislative amendments to the budget will likely work out those differences. Items funded from available General Fund revenues include: (13) (14)

- $472 million non-recurring in FY 2025 for several disaster recovery and assistance initiatives.

- $146 million recurring in FY 2026 for the first year of the new Education Freedom Scholarship

- $198 million non-recurring in FY 2026 for one-time $2,000 bonuses for public school teachers.

- $23 million for grants to targeted school districts. These dollars are accounted for as both non-recurring in FY 2025 and recurring beginning in FY 2026.

- $6 million to implement a new law related to immigration enforcement—including $5 million recurring and $1 million non-recurring.

Changes to the FY 2025 Budget

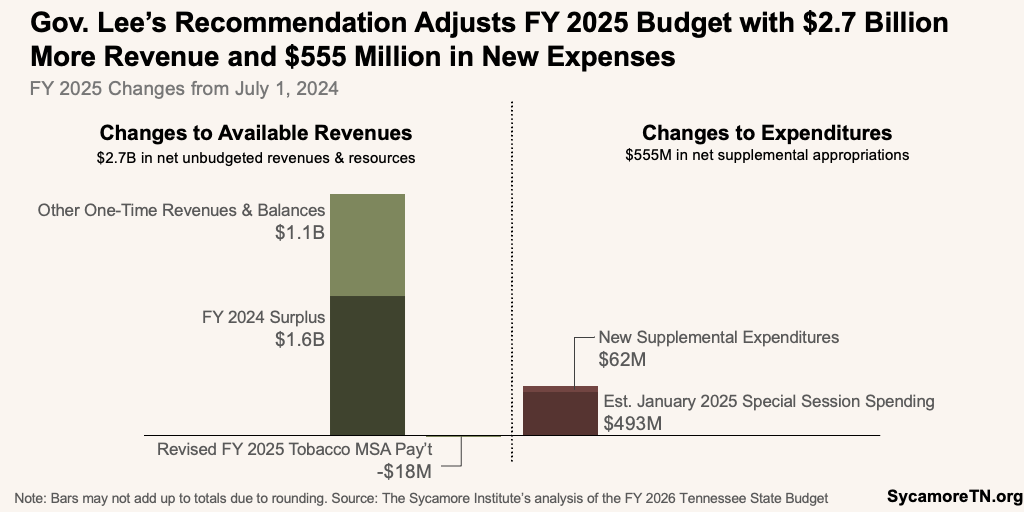

The Budget reflects $555 million in supplemental spending in FY 2025, the current fiscal year (Figure 5). The governor makes supplemental requests each year because actual revenue and spending needs often differ from original estimates. This year’s number includes the $493 million impact in FY 2025 of the special session spending discussed above. Of the remainder, $47 million would cover increased service costs associated with children in the Department of Children’s Services’ custody.

Figure 5

The Budget also anticipates an additional $2.7 billion in available funds for FY 2025 beyond what was initially planned (Figure 5). This includes the net effect of the FY 2024 surplus discussed above, $1.2 billion in previously unbudgeted revenues, and $18 million less than expected in the state’s annual payment from the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. The largest sources of unbudgeted revenues are the treasurer’s earnings, the unused contingency for an FY 2024 tax shortfall, and the unused funds for franchise tax refunds discussed above.

Unlike in many prior years, the Budget does not include a mid-year revision of the current year’s tax projection. Five months into the fiscal year, actual collections are largely tracking with projections. General Fund collections were about $19 million (or 0.2%) below estimates for the fiscal year through January. (15)

Figure 6

The FY 2026 Recommended Budget

The FY 2026 recommended budget totals $59.5 billion from all revenue sources, a decrease of 1.8% (or $1.1 billion) below estimates for the current year. The funding mix is 50% state dollars, 35% federal, and 16% from tuition, bonds, and other sources. Health and Social Services (46%) and Education (26%) account for over 70% of total expenditures (Figure 6).

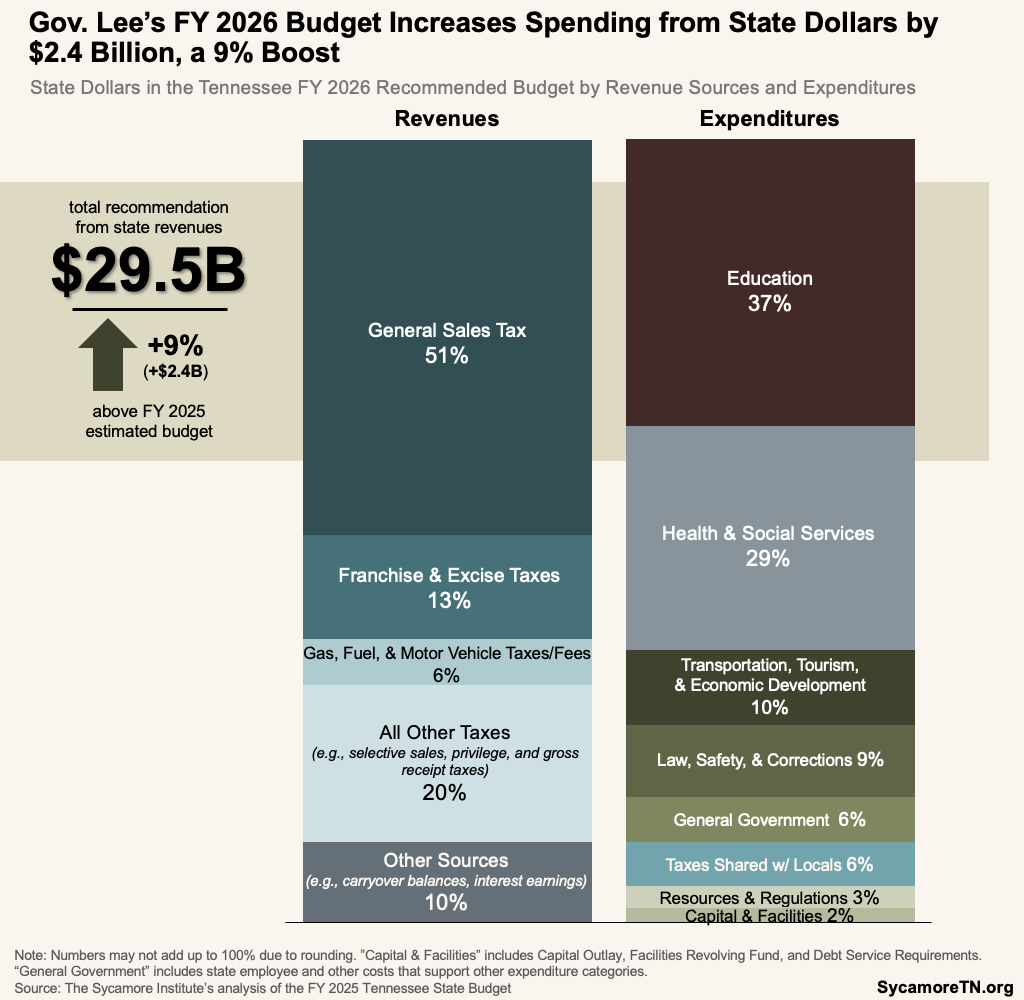

State dollars in the recommended budget total $29.5 billion, an increase of 9% (or $2.4 billion) from the current year. Most of the state dollars in the FY 2026 budget come from taxes—the largest of which are sales and business taxes (Figure 7). Education (37%) and Health and Social Services (29%) account for almost two-thirds of expenditures from state appropriations.

Figure 7

The General Fund in Context

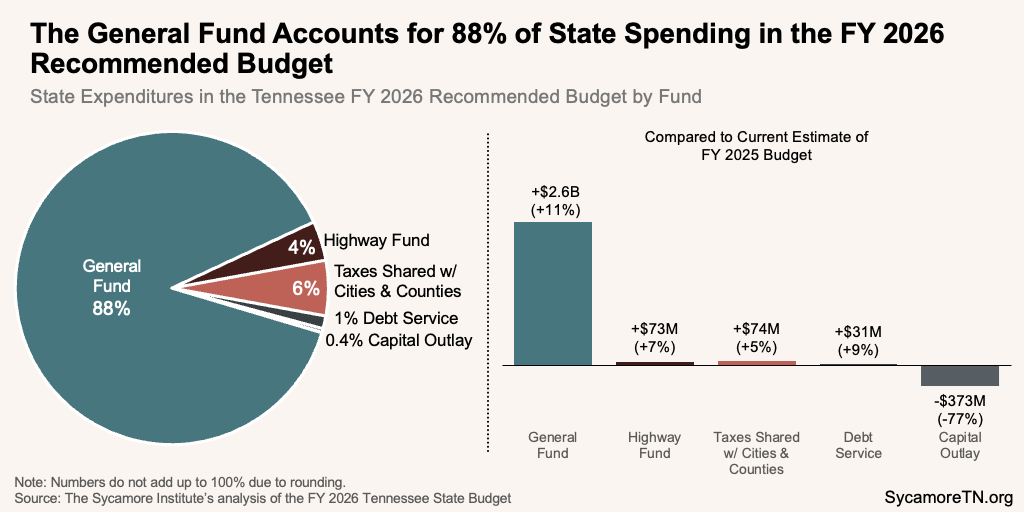

The administration’s recommended budget often focuses on state dollars in the General Fund, which would account for 88% of all state spending in FY 2026 (Figure 8). That number does not include state appropriations for Capital Outlay and the Facilities Revolving Fund, which some calculations include with the General Fund because General Fund revenue partly pays into those funds.

Figure 8

Recommended Increases and One-Time Spending and Allocations

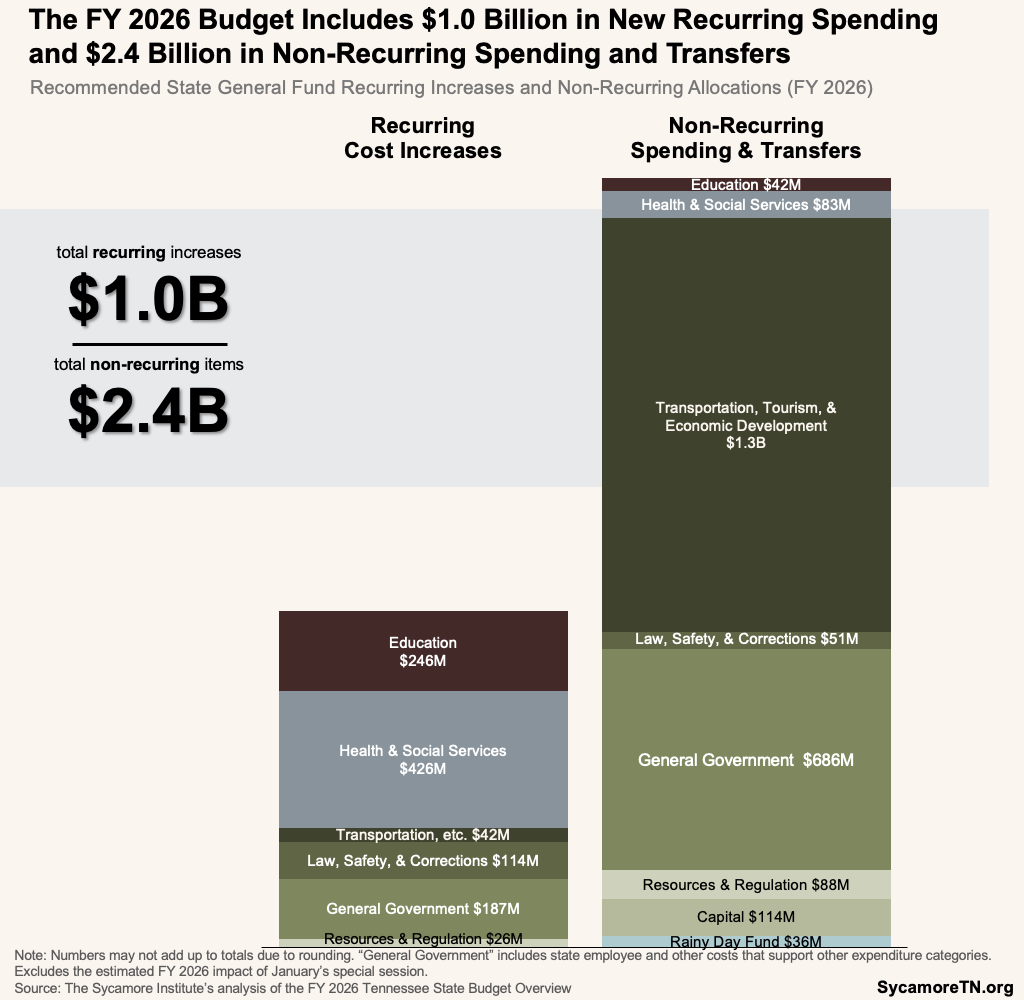

The Budget recommends $1.0 billion in new recurring General Fund spending and $2.4 billion in non-recurring spending and transfers in FY 2026 (Figure 9).[1] Recurring spending is expected to occur every year and is added to the budget’s base, while non-recurring expenditures are one-time. The largest increases are highlighted below and exclude the estimates for special session spending discussed earlier.

The Budget’s Largest Recurring Increases

- $281 million to fund inflationary cost increases, a routine change in the federal match rate, and other activities related to TennCare, the state’s Medicaid program.

- $207 million for public K-12 education, which includes funding for teacher pay increases, growth in the state’s school funding formula, and other public school initiatives.

- $191 million for personnel-related costs for state employee salary and health insurance increases.

The Budget’s Largest Non-Recurring Allocations

- $1.0 billion General Fund transfer to the Highway Fund for transportation projects.

- $221 million for activities and projects related to public safety.

- $206 million for Capital Outlay and other smaller capital projects and maintenance within agency budgets.

Figure 9

Highlights and Initiatives

This section includes summaries and context for initiatives affecting the FY 2026 recommended budget. Unless otherwise noted, the recurring and one-time spending plans discussed in the previous sections include the costs discussed below.

TISA School Funding Formula Increases

The Budget includes $6.8 billion total for the Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement (TISA)— the state’s school funding formula. Within this total is: (16) (17)

- A $164 million recurring increase to cover enrollment growth, teacher pay raises, and a 3.1% increase to the base per pupil amount—from $7,075 per student in FY 2025 to $7,295 in FY 2026. Although the TISA statute does not include automatic inflationary increases, this recommended increase aligns with prior years’ formula increases.

- Another $80 million in the FY 2025 base that was projected to go out to school districts in the current school year but did not due to lower-than-projected student enrollment. As a result, the practical TISA formula increase to school districts in FY 2026 may be closer to $244 million, depending on actual student enrollment.

- Formula funding increases for career and technical education.

- Increases totaling $25 million, including $5 million recurring and $20 million non-recurring, for the fast growth fund which provides supplemental funding to school districts experiencing high student enrollment growth.

Within the proposed TISA increase is $87.5 million in state funding for teachers’ salaries. Local school districts will be required to put in $37.5 million for a total of $125 million. (16) Lawmakers have routinely enacted dedicated recurring increases for teacher pay since FY 2016. Despite these efforts, Tennessee teachers’ average pay growth has not kept up with inflation. After adjusting for inflation, teachers’ average pay during the 2022-2023 school year was still about 20% lower than in 2010 (Figure 10). For context, median earnings for Tennessee workers with bachelor’s degrees saw 4% real growth. (18) (19) In addition to salary increases that result from the approved budget, teachers will also receive a one-time $2,000 bonus under legislation passed in January’s special session.

Figure 10

Post-Secondary Scholarships and Lottery Funds

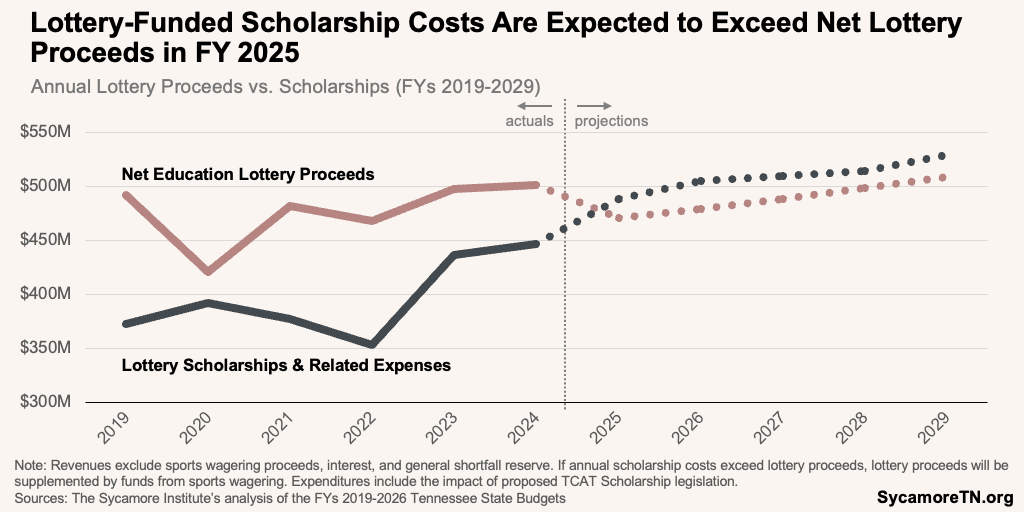

Gov. Lee’s budget proposes expanding lottery-funded scholarships for Tennessee Colleges of Applied Technology (TCATs) students by about $12.1 million annually. Students already have access to TN Promise and Reconnect—“last-dollar” scholarships that help cover tuition and fees at TCATs and community colleges. The proposal, however, would cover other costs like required textbooks, tools, and equipment.

Figure 11

The governor’s proposal would add additional costs to an already growing lottery-funded scholarship program at a time when lottery proceeds have been volatile. Scholarship costs have grown in recent years due to increases in the HOPE scholarship and dual enrollment grants, while sports betting competition has taken a toll on lottery proceeds. In fact, the FY 2026 budget predicts that lottery proceeds alone will fall short of scholarship costs beginning in FY 2025 (Figure 11). A portion of the sports betting-related privilege tax began supplementing these dollars in FY 2021, but under the new Education Freedom Scholarship Act, those dollars will only be available to the Lottery Account in case of a shortfall. (22)

Transportation Funding

Tennessee’s transportation revenues have failed to keep up with the costs of building roads despite recent efforts. The 2017 IMPROVE Act increased taxes and fees that fund the state’s Highway Fund in FYs 2018-2020, and the 2023 Transportation Modernization Act introduced higher electric vehicle fees and new hybrid fees. However, the purchasing power of these types of excise taxes and fees tend to fall over time because they are not responsive to inflation. As a result, Tennessee’s Highway Fund revenues fell in value by almost 33% between FYs 2021 and 2024 after adjusting for inflation in highway construction costs (Figure 12). (23)

Gov. Lee’s FY 2026 recommendation continues to chip away at these structural funding issues in the Highway Fund. In addition to the $1 billion non-recurring General Fund subsidy discussed above, the administration also proposes legislation to divert an estimated $80 million per year in sales tax collected on tires from the General Fund to the Highway Fund. Similarly, in FY 2024, $3.3 billion was transferred from the General Fund, but the state continues to face a backlog of road projects.

Figure 12

Housing

The Budget includes two initiatives to increase housing supply and affordability in the state—focusing on rural areas. These include:

- A $60 million non-recurring investment to create a Starter Home Revolving Fund within the Tennessee Housing Development Agency. The purpose is to “increase the availability of affordable starter homes across the state with a focus on rural areas.”

- A $30 million recurring revenue reduction associated with authorizing and implementing a 2024 state law that provides tax credits for affordable housing projects. Half of the credits issued would be required to support projects in rural areas.(24) (25)

Available data suggest that housing costs may be unaffordable for some in many parts of the state. For example, one common measure of housing affordability compares median home sales prices to median household incomes. Generally, a ratio of 3.0 is considered affordable (i.e., the typical home costs about three times the typical income). Data for 2023 show that only 17 counties had ratios near or below the affordability threshold. All but one of Tennessee’s 23 urban counties—representing 67% of the state’s population—and 56 of the state’s 72 rural counties—representing 28% of the population—were above this threshold (Figure 13).[2] (26) (27) (28) (29)

Figure 13

Child Care

The Budget includes several items intended to expand access to childcare. These include:

- $5.9 million recurring to expand eligibility for Smart Steps, a program providing childcare assistance for families with up to 85% of the state median income. The increase would support working parents pursuing post-secondary degrees who earn up to 100% of the median income.

- $7.2 million recurring for WAGE$ program expansion, which supplements childcare salaries to improve worker retention. Expansion of WAGE$ was one of several recommendations made by a 2022 Tennessee Child Care Task Force.(30)

- $15 million non-recurring for the final year of a three-year investment in childcare improvement grants. Improvement fund grants are dedicated to helping nonprofits establish new or improve existing childcare centers.(1)

Debt for Capital Outlay

The recommendation includes $114 million in state appropriations for projects from the Capital Outlay Fund and another $930 million in general bond authority (i.e., debt). State and local governments routinely take on debt to pay for capital projects, but Tennessee has not consistently done so in about a decade. (4) The administration testified that the benefits of beginning needed capital projects now outweighed the costs of taking on new debt. That is, the interest costs of borrowing would be a better deal for the state than the effects of rapidly rising construction costs—particularly considering the state’s triple-A credit rating, which typically gives access to the best interest rates. (1)

TennCare Shared Savings

For the third year, the Budget proposes new multi-year investments using federal TennCare shared savings dollars. These and past investments include:

- The FY 2026 recommendation proposes using $256 million in shared savings received in FY 2025 to expand enrollment in TennCare’s long-term services and supports (LTSS) programs and for LTSS workforce development activities over a span of six years. Another $100 million in FY 2025 shared savings has been loaned to counties affected by Hurricane Helene.

- The FY 2025 budget allocated $318 million in shared savings received in FY 2024 and other balances to rural and behavioral health activities. These activities will occur over the course of five years.

- The FY 2024 budget allocated $331 million, which was received in FY 2023, to cover Medicaid eligibility expansions for low-income mothers and children. The dollars will be spent over the course of eight years.

FY 2026 Spending Reductions

The Budget proposes reductions totaling $111 million recurring and $31 million non-recurring. The non-recurring reduction reflects replacing state dollars with other temporary sources of funding. The largest recurring reductions include:

- A $48 million reduction to the state’s recurring obligations for funding other post-employment benefits (OPEB)—which includes health insurance for retired state employees. This reduced obligation comes on the heels of $550 million in one-time deposits in recent years to help pay down those long-term liabilities.

- A $21 million reduction from savings to the TennCare CHOICES 3 program. This program covers long-term services and supports for adults at-risk of needing a level of care provided by nursing homes.

FY 2025 State Tax Revenue Growth

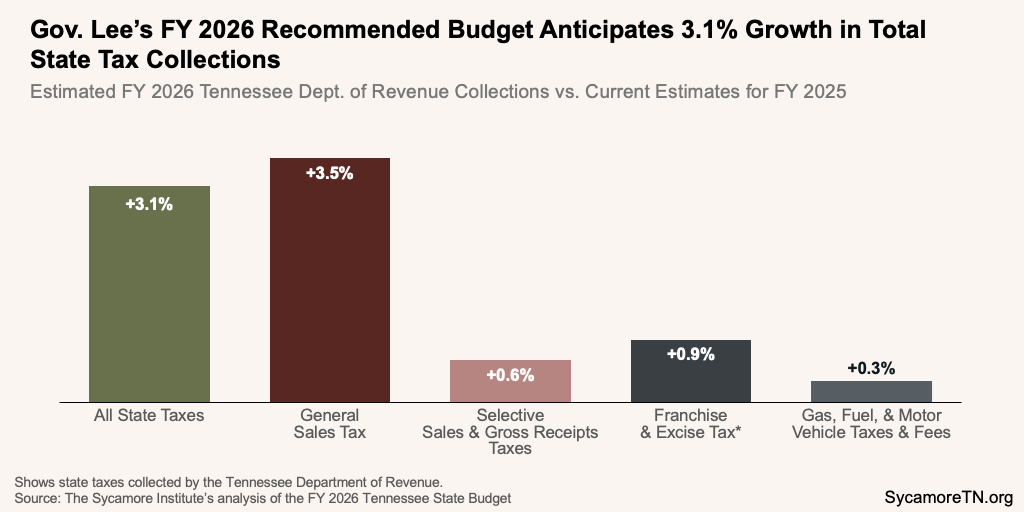

The Budget expects total state tax collections to grow by 3.1% (or $678 million) in FY 2026—more in line with the growth rates the state experienced before the pandemic and recent tax cuts. The state experienced rapid pandemic-era growth in tax collections and then adopted several franchise and excise tax changes (Figure 14). The FY 2026 growth rate is closer to those the state experienced before these changes and the pandemic but reflects sluggish growth in nearly all tax types but the general sales tax (Figure 15).

The State Funding Board recommended a range of 1.25% to 2.15% growth in recurring state tax revenues for FY 2026 based on expert estimates that ranged from 2.52% to 4.53%. The recommended range for recurring General Fund revenues was 1.00% to 2.00% based on expert estimates that ranged from 1.48% to 3.76%. As has been in the case in recent years, the recommendation is based on rates at the top of the Funding Board’s recommended ranges.

The direction and degree of expected change vary by revenue type (Figure 15):

- +3.5% gain ($502 million) in general sales tax collections.

- +0.3% gain ($5 million) in gas, fuel, and motor vehicle taxes and fees collections.

- +0.9% gain ($36 million) in franchise and excise tax collections.

- +0.6% gain (+$6 million) in selective sales and gross receipts taxes collections.

Figure 14

Figure 15

Franchise Tax Refunds

The state plans to refund all but $113 million of the almost $1.6 billion budgeted for franchise tax refunds in 2024. Businesses had until November 30, 2024, to request a refund. (31) As of December 20, 2024, the state had already refunded $1.3 billion. The Budget holds back $151 million for submitted but not yet processed claims and another $11 million for businesses impacted by Hurricane Helene, which were granted an application extension. The remaining $113 million in non-refunded dollars reverted to the General Fund and are used as a non-recurring revenue source in this budget (discussed above).

Figure 16

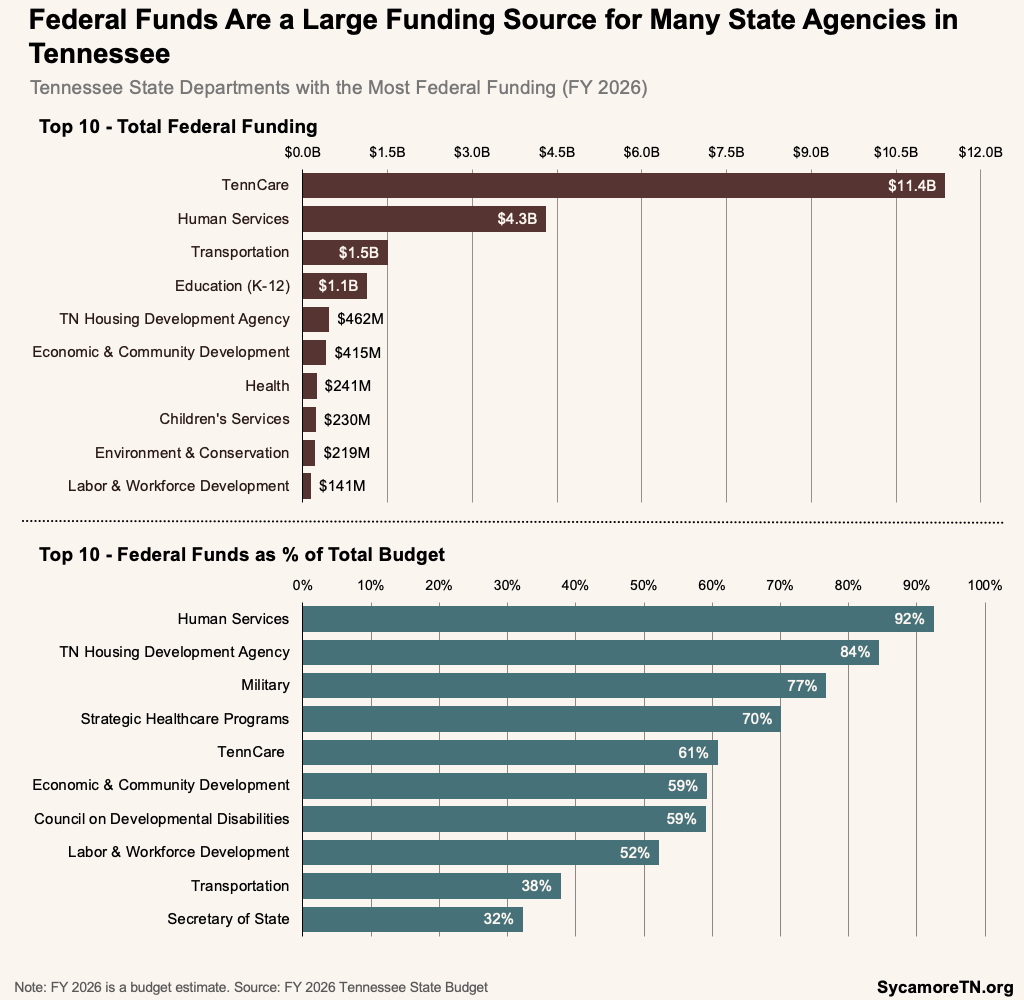

Federal Funding

The FY 2025 estimate reflects large balances associated with COVID-related federal funding (Figure 16). Many of these funds had to be obligated by states by December 31, 2024, and spent by December 31, 2026. As a result, these expenses are likely to ultimately be spread over FYs 2025-2027 once actual expenditures are reported.

The Budget reflects no significant federal funding cuts in FYs 2025 or 2026. President Trump and federal lawmakers have signaled an intent to cut federal spending, but details about those reductions have not yet taken form. When they do, they may or may not ultimately impact agencies’ budgets across state government—some of which depend on federal dollars more than others (Figure 17).

Figure 17

Rainy Day Reserves

The Budget recommends a $36 million deposit to the state’s rainy day fund in FY 2026, bringing the Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations balance up to $2.2 billion.[3] This balance would be the highest ever (Figure 18). These rainy day reserves are a tool of last resort should Tennessee need to respond to an economic downturn. (32) Reserve balances provide a cushion during a recession, when demand for state programs and services increases but the revenues that fund them decrease.

- This balance would cover about 31 days of state-funded General Fund operations at the recommended FY 2026 levels. This is about 6 days more cushion than just before states began to feel the effects of the Great Recession.

- The Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations would exceed its statutory target by about $295 million. State law sets a target for that fund at 8% of General Fund revenues, and the FY 2026 recommended balance represents about 9.2%.[4] (32)

Figure 19

Key Budget Resources

- Sycamore’s Tennessee State Budget Primer

- FY 2026 Tennessee State Budget

- Budget Overview for the FY 2026 Tennessee State Budget

- Lee’s 2025 State of the State Address

- FY 2026 Budget Presentation to the House and Senate Finance Committees

- Archive of Tennessee State Budgets

[1] Excludes $171.8 million recurring and $198.4 million non-recurring associated with the January special session. (2)

[2] Urban/rural county designations are based on definitions from the 2020 Census.

[3] Our analyses of the state’s rainy day fund typically also includes the TennCare Reserve, which has also been used in the past to respond to economic downturns. However, FY 2026 budget documents show that a significant portion of those balances are already obligated for specific purposes (e.g., shared savings, IT improvements), so we have excluded them from this summary.

[4] Calculated by adding Department of Revenue and other state revenue allocations to the General Fund, Education Fund, and Debt Service Fund minus the Gas Tax allocation to the Debt Service Fund (from page A-67 of the Budget).

References

Click to Open/Close

References

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee State Budget for FY 2025-2026. [Online] February 10, 2025. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/2026BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. Budget Overview Fiscal Year 2025-2026. [Online] February 10, 2025. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/overviewspresentations/FY26Recommended_Final.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Gross Domestic Product: Chain-type Price Index [GDPCTPI]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Online] February 2025. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPCTPI.

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee State Budgets for FYs 2001-2002 through 2024-2025. [Online] 2001-2024. Available from https://www.tn.gov/finance/fa/fa-budget-information/fa-budget-archive.html.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. FY 2024 Agency Reversions.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid CMS-64 CAA 2023 Increased FMAP Expenditure Data Collected through MBES/CBES. [Online] https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financial-management/state-budget-expenditure-reporting-for-medicaid-and-chip/expenditure-reports-mbes/cbes/medicaid-cms-64-ffcra-and-caa-increased-fmap-expenditure-data-collected-through-mbes/index.html#:~:text=Specifica.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. Budget Overview to the FYs 2018-2019 through 2023-2024 Budgets. 2018-2023.

- —. Budget Overview to the FY 2024-2025 State Budget. [Online] February 5, 2024. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/overviewspresentations/FY25%20Budget%20Overview%20Final.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 1061 (2018). [Online] May 21, 2018. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/110/pub/pc1061.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 405 (2019). [Online] May 17, 2019. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/111/pub/pc0405.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 651 (2020). [Online] April 2, 2020. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/111/pub/pc0651.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 760 (2020). [Online] June 30, 2020. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/111/pub/pc0760.pdf.

- Tennessee General Assembly. SB 6005 / HB 6005 in the First Extradordinary Session of the 114th General Assembly. The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of bill and amendment language. [Online] January 2025. Documents available at https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/Default.aspx?BillNumber=SB6005&GA=114.

- Fiscal Review Committee. SB 6001 – HB 6004 Fiscal Memorandum. Tennessee General Assembly. [Online] January 28, 2025. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/114/Fiscal/FM0013.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. January Revenues. [Online] February 18, 2025. https://www.tn.gov/content/tn/finance/news.revenues.html.

- Tennessee General Assembly. HB 1409 / SB 1431 (as introduced). [Online] February 14, 2024. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/114/Bill/HB1409.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Finance & Administration. FY 2026 Budget Presentation. [Online] February 11, 2025. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/overviewspresentations/FY26%20Budget%20Presentation.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (Table S2001). [Online] 2011-2024. Available from https://www.data.census.gov.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Online] February 2025. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL.

- National Education Association. Historical Rankings and Estimates Reports. [Online] Available from https://www.nea.org/research-publications.

- National Educaton Association. Educator Pay Data 2024: Teacher Pay & Per Student Spending. [Online] September 2024. https://www.nea.org/resource-library/educator-pay-and-student-spending-how-does-your-state-rank/teacher.

- Tennessee General Assembly. Senate Amendment 1 to SB 6001 (adopted). [Online] January 2025. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/114/Amend/SA6002.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Transportation. The National Highway Construction Cost Index (NHCCI). [Online] December 31, 2024. https://data.transportation.gov/Research-and-Statistics/NHCCI/r94d-n4f9/about_data.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 971 (2024). [Online] 2024. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/113/pub/pc0971.pdf.

- Tennessee General Assembly. SJR 27 (as introduced). [Online] January 15, 2024. https://www.capitol.tn.gov/Bills/114/Bill/SJR0027.pdf.

- Tennessee Housing Development Agency. 2023 Home Sales: New and Existing Homes by County. [Online] https://thda.org/research-reports/tennessee-housing-market/tennessee-home-sales-data.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE). [Online] https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/saipe/#/?s_state=47&s_county=&s_district=&s_geography=county&s_measures=mhi.

- —. Urban and Rural: County-level 2020 Census Urban and Rural Information for the U.S., Puerto Rico, and Island Areas sorted by state and county FIPS codes [10 MB]. [Online] September 2023. [Obtained on December 12, 2024.] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural.html.

- —. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023 (CO-EST2023-POP). [Online] June 2024. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-counties-total.html.

- Public Consulting Group. Tennessee Child Care Task Force: Final Report. [Online] December 2022. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/human-services/documents/TN%20CCTF%20Final%20Report_12.15.22.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 950 (2024). [Online] 2024. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/113/pub/pc0950.pdf.

- —. TN Code § 9-4-211. [Online] Accessed via Lexis.