Key Takeaways

- A temporary expansion of federal premium subsidies for Affordable Care Act Marketplace plans will expire on December 31, 2025.

- In 2025, nearly 643,000 Tennesseans enrolled in ACA Marketplace plans—more than twice the number who enrolled in 2020, before Congress enacted the temporary subsidy increases.

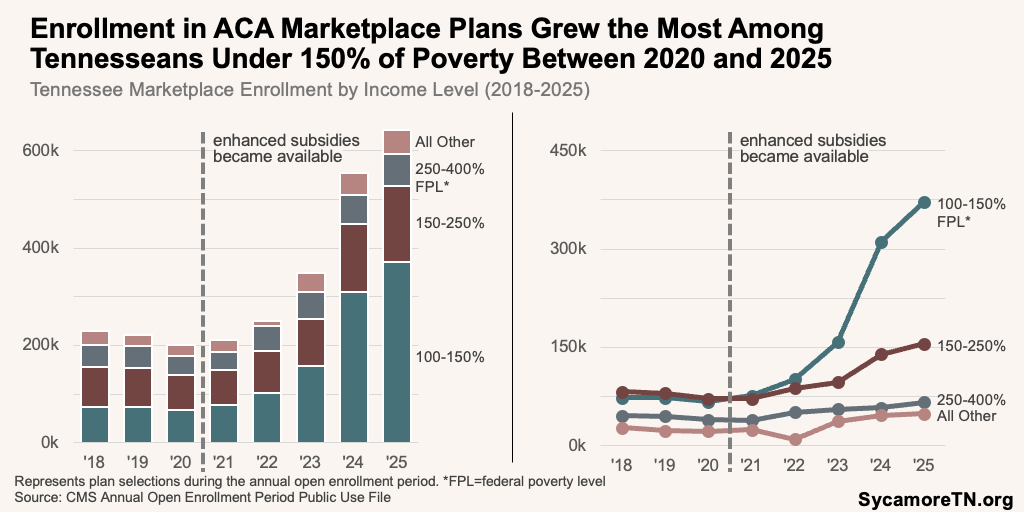

- Enrollment increased at all income levels but was highest among enrollees with incomes between 100-150% of the poverty level.

- Without the enhanced subsidies, Tennessee enrollees will face higher premiums, leading some to drop Marketplace coverage to go uninsured or switch to other plans—such as employer coverage.

- Marketplace insurers expect higher 2026 premiums as they anticipate a costlier enrollee pool without enhanced subsidies.

- An increase in the number of uninsured people in Tennessee can have broad effects on individuals and the health care system.

- Without the temporary enhanced subsidies, however, both insurers and enrollees may have a greater incentive to control costs.

Congress is currently debating whether to extend temporary subsidy increases for health insurance coverage purchased on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace. Continuing the increased premium subsidies in their current form is estimated to come at a net cost of about $23 billion in federal FY 2026 and $350 billion over 10 years. (1) This issue brief provides basic information about the subsidies and recent data on Marketplace enrollment and health insurance coverage in Tennessee.

Background

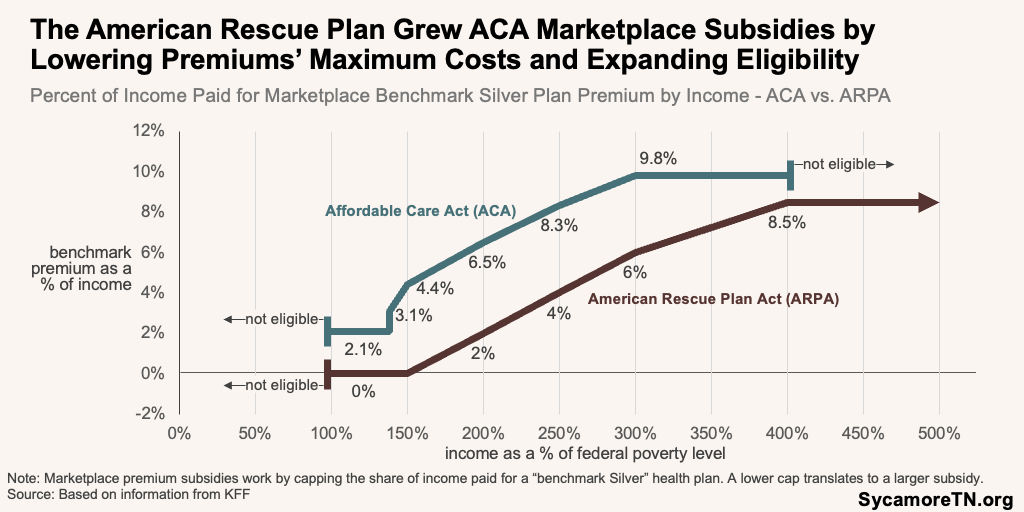

The American Rescue Plan (ARPA) temporarily expanded premium subsidies for ACA plans. The ACA provides income-based subsidies tied to caps on premium costs—known as advanced premium tax credits (APTCs)—for health plans purchased on the Marketplace (see text box). As a COVID relief measure, ARPA and then the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act temporarily increased those tax credits by boosting the ACA’s premium caps and expanding eligibility for 2021-2025 (Figure 1). (2)

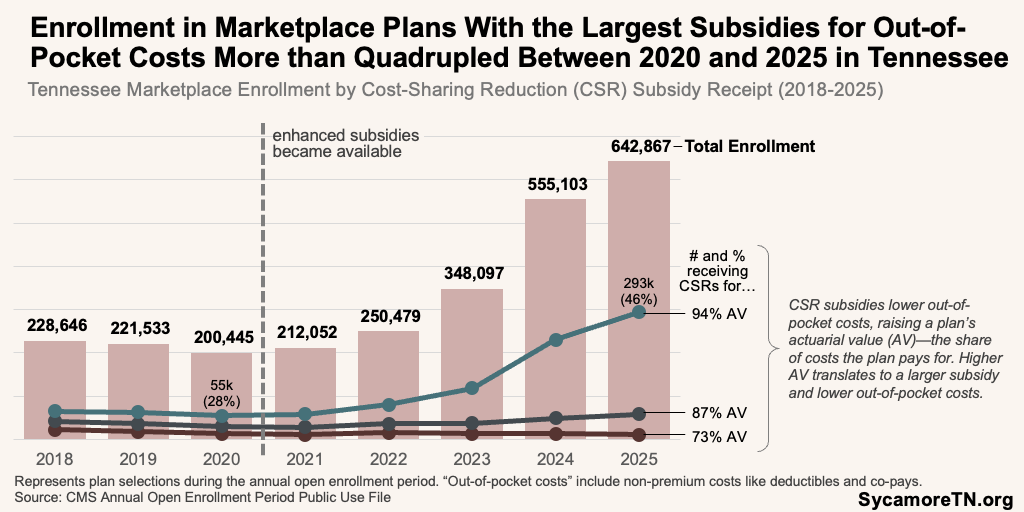

ARPA’s larger premium subsidies also drove increased enrollment in plans with subsidies that reduce out-of-pocket spending requirements (i.e., deductibles, co-pays, coinsurance). In addition to APTCs, the ACA also subsidizes out-of-pocket costs with income-based cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) for certain plans (see text box). Although eligibility for CSRs has not changed, the lower premiums from the larger APTCs has spurred more enrollment in CSR-eligible plans. (3)

Figure 1

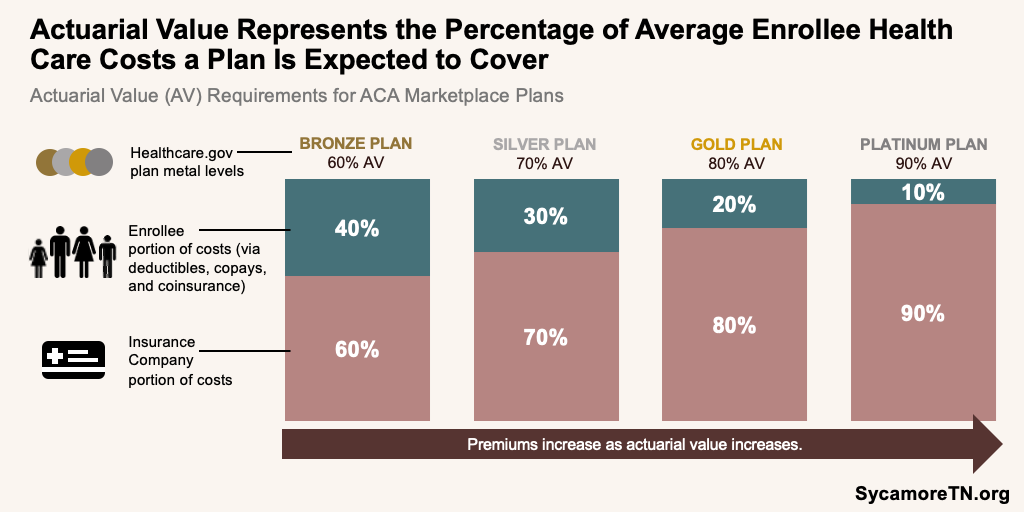

Figure 2

How the ACA’s Marketplace Subsidies Work

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides income-based subsidies to help cover both the premiums and out-of-pocket costs for health plans purchased on the healthcare.gov Marketplace. The value of the subsidies—which the federal government pays directly to insurance companies—are based on 1) a cap on share of income paid for certain premiums, 1) the cost of a so-called “benchmark Silver” plan, and 3) a plan’s actuarial value. Actuarial value (AV) is the expected share of an average enrollee’s costs that a plan pays for. AV is also what determines the differences in Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum plans (Figure 2). Here’s an illustration of how that works.

John has an annual income of about $30,000—or roughly 200% of poverty. With the current enhanced premiums, he is eligible for a 2% cap, meaning he would pay no more than 2% of his annual income towards premiums for the so-called “benchmark plan.” For him, this works out to about $600 a year or $50 per month. If the monthly cost of the benchmark Silver plan is $500, the subsidy would equal $450 per month (i.e., $500 minus John’s $50 cap). John could apply that $450 subsidy either to the benchmark plan and pay $50 per month or to another plan and pay the difference between the $450 subsidy and that plan’s premium. He could, for example, select a cheaper Bronze plan that is entirely covered by the $450 subsidy and pay no premium.

The subsidies are awarded as “advanced premium tax credits” (APTCs)—meaning John would apply for the subsidy up front based on what he knows about his income at the time. The federal government pays the $450 per month subsidy directly to his insurance company, and he pays the difference between the subsidy and his plan’s premium. When he files his taxes at the end of the year, he will reconcile the subsidy based on his actual income and may owe or receive any difference.

If John buys any Silver plan, he is also eligible for cost-sharing reductions (CSRs), which lower out-of-pocket costs like deductibles, copays, and coinsurance. These work by raising his plan’s AV. At 200% of poverty, he is eligible for an 87% AV—compared to a Silver plan’s typical 70% AV. This essentially boosts the value of his Silver plan to a Platinum plan. His insurer will reduce his out-of-pocket requirements up front (e.g., a lower deductible), and as he uses his plan, the federal government will directly reimburse the insurer for the extra costs of providing those lower cost-sharing requirements.

Marketplace Enrollment in Tennessee

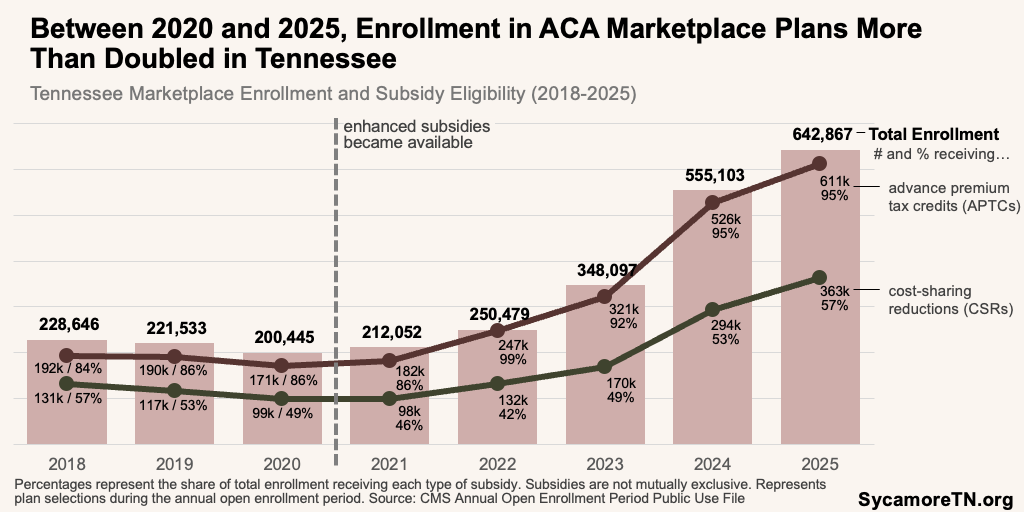

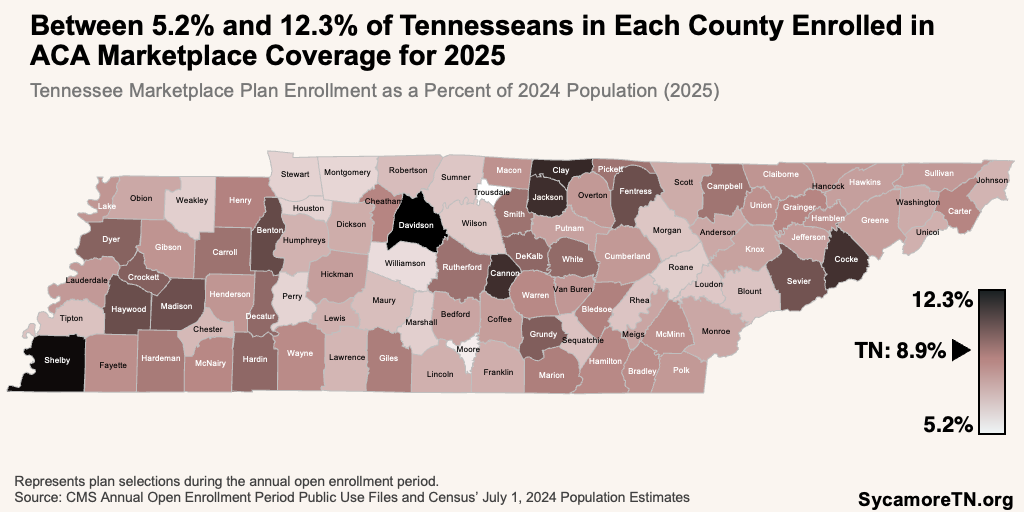

In 2025, nearly 643,000 Tennesseans enrolled in ACA Marketplace plans—more than twice the number enrolled in 2020 before Congress enacted the temporary subsidy increase (Figure 3). (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) Tennesseans in all 95 counties enrolled in plans—from as few as 5.2% of Trousdale County residents to as many as 12.3% in Davidson (Figures 4 and 5). (11) (12) Other key trends include:

- Both the number and share of Tennessee enrollees receiving either APTCs or CSRs also increased during this period (Figure 3).

- Between 2020 and 2025, the number of Tennessee enrollees with the most generous CSR plans more than quadrupled (Figure 6). Only those with incomes between 100-150% of poverty are eligible for these plans. In 2020, about 55,000 enrollees—or 28% of all Tennessee enrollees—had Silver plans with CSRs that boosted the AV from 70% to 94%. By 2025, that had increased to 293,000—or 46% of all enrollees.

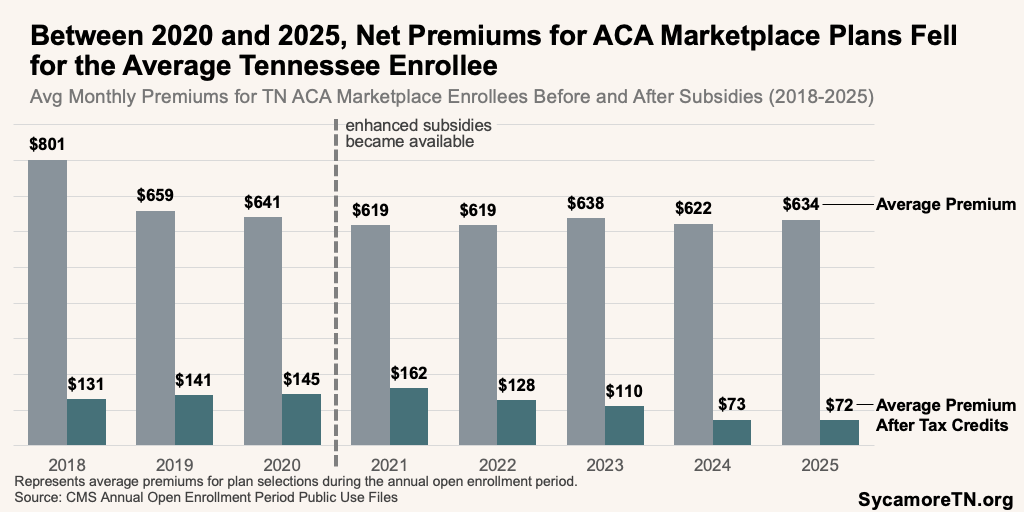

- During this period, average enrollee premiums—both before and after the application of premium subsidies—declined even without adjusting for inflation (Figure 7).

- The trends above suggest that—on average—Tennessee enrollees paid less and selected more generous plans in 2025 than they did in 2020, even without adjusting for inflation.

- Enrollment increased at all income levels but was strongest among enrollees with incomes between 100-150% of the poverty level (Figure 8). Between 2020 and 2025, enrollment in this group increased by almost 460%—from about 49,000 to over 372,000.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Looking Ahead

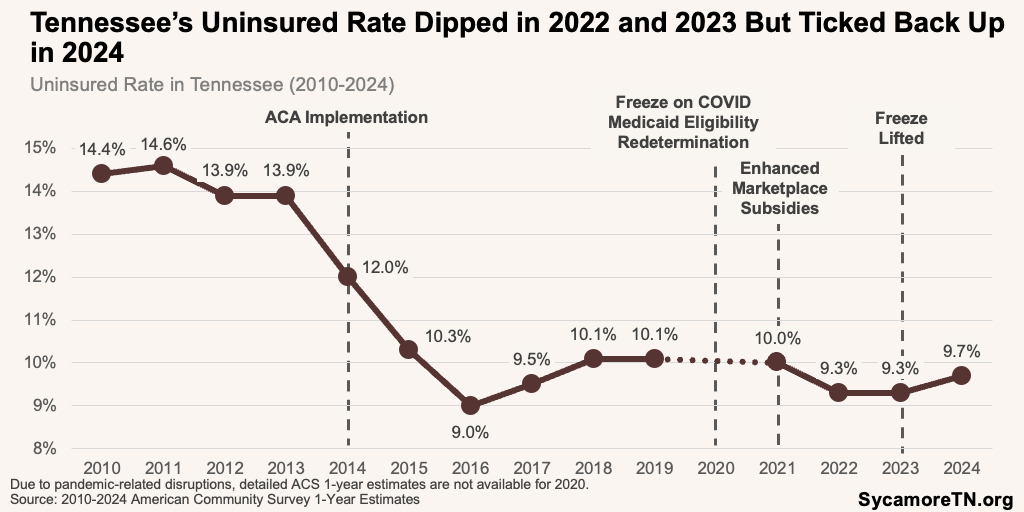

Without the enhanced subsidies, Tennessee enrollees will face higher premiums, leading some to drop Marketplace coverage to go uninsured or switch to other plans—such as employer coverage. Analyses suggest average premiums could more than double, with the biggest effects on small business owners, gig workers, rural residents, older adults with incomes over 400% of poverty, and households earning between $100,000 and $150,000. (13) (14) (15) An estimated 142,000 to 203,000 Tennesseans could forgo insurance coverage as a result of the price increases. (16) (17) For context, Tennessee’s uninsured rate fell in 2022 and 2023 due to expanded subsidies and Medicaid eligibility redetermination changes but began rising again in 2024 (Figure 9). (18)

Figure 9

Marketplace insurers expect higher 2026 premiums as they anticipate a costlier enrollee pool without enhanced subsidies. (19) Those most likely to drop coverage are lower-income individuals who can no longer afford a plan or healthier people who see less value at higher prices, which increases prices for those who remain. Nationally, the proposed 2026 rate hikes are the largest in eight years. In Tennessee, Marketplace insurers have proposed increases of 0.3% (Alliant Health Partners), 28% (Oscar), 38% (Celtic), and 41% (BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee). (20)

An increase in the number of uninsured people in Tennessee can have broad effects on individuals and the health care system. Uninsured individuals often delay care due cost—especially low-income individuals—which can worsen health outcomes. (21) (22) Uninsurance can also increase reliance on emergency services and uncompensated care, putting financial strain on hospitals and providers. (23) (24) (25) (26) (27) (28)

Without the enhanced subsidies, however, both insurers and enrollees may have a greater incentive to control costs. When federal subsidies cover more of the premium cost, enrollees have less incentive to shop for lower-cost plans, and insurers face less pressure to keep premiums down. (29) (30) (31) Meanwhile, when enrollees pay less at the point of care (i.e., primary care, hospital) via plans with a higher AV, they tend to be less sensitive to both health care prices and utilization. This can come with trade-offs that include both protecting individuals from the high costs of needed or effective care while potentially increasing overall health care spending. (32) (33) (34)

Parting Words

Congress is currently considering whether to extend the temporary enhanced Marketplace subsidies or pursue alternative approaches that modify or phase them out. Each option carries trade-offs for affordability, federal spending, market stability, and coverage levels. Tennessee’s recent experience illustrates how these subsidies have influenced coverage levels, plan selection, premiums and the overall individual health insurance market.

References

Click to Open/Close

References

1. Congressional Budget Office. The Estimated Effects of Enacting Selected Health Coverage Policies on the Federal Budget and on the Number of People With Health Insurance. [Online] September 18, 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61734 2. McDermott, Daniel, Cox, Cynthia and Amin, Krutika. Impact of Key Provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 COVID-19 Relief on Marketplace Premiums. KFF. [Online] March 15, 2021. https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/impact-of-key-provisions-of-the-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021-covid-19-relief-on-marketplace-premiums/.

3. Ortaliza, Jared, et al. Inflation Reduction Act Health Insurance Subsidies: What is Their Impact and What Would Happen if They Expire? KFF. [Online] July 26, 2024. https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/inflation-reduction-act-health-insurance-subsidies-what-is-their-impact-and-what-would-happen-if-they-expire/.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2018 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/marketplace-products/2018-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

5. —. 2019 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/marketplace-products/2019-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

6. —. 2020 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/marketplace-products/2020-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

7. —. 2021 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2021-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

8. —. 2022 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2022-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

9. —. 2023 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2023-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

10. —. 2024 OEP State-Level Public Use File. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2024-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

11. —. 2025 OEP State-Level and County-Level Public Use Files. [Online] [Cited: October 16, 2025.] Downloaded from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2025-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

12. U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2024 (CO-EST2024-POP). [Online] July 2024. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-counties-total.html.

13. Patzman, Andrew, Strong, Kendall and Harootunian, Lisa. Enhanced Premium Tax Credits: Who Benefits, How Much, and What Happens Next? Bipartisan Policy Center. [Online] October 15, 2025. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/issue-brief/enhanced-premium-tax-credits-who-benefits-how-much-and-what-happens-next/.

14. Cotter, Lynne. Which Congressional Districts Could See the Greatest ACA Premium Payment Increases? . KFF. [Online] October 9, 2025. https://www.kff.org/quick-take/which-congressional-districts-could-see-the-greatest-aca-premium-payment-increases/.

15. Lo, Justin, et al. ACA Marketplace Premium Payments Would More than Double on Average Next Year if Enhanced Premium Tax Credits Expire. KFF. [Online] September 30, 2025. https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/aca-marketplace-premium-payments-would-more-than-double-on-average-next-year-if-enhanced-premium-tax-credits-expire/.

16. Buettgens, Matthew, et al. 4.8 Million People Will Lose Coverage in 2026 If Enhanced Premium Tax Credits Expire. Urban Institute and the Commonwealth Fund. [Online] September 2025. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/48-million-people-will-lose-coverage-2026-if-enhanced-premium-tax-credits.

17. Burns, Alice, et al. How Will the 2025 Reconciliation Law Affect the Uninsured Rate in Each State? Allocating CBO’s Estimates of Additional Uninsured People Across the States. KFF. [Online] August 20, 2025. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/how-will-the-2025-reconciliation-law-affect-the-uninsured-rate-in-each-state/.

18. U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. [Online] 2015-2024. Accessed from http://data.census.gov.

19. King, Robert and Hooper, Kelly. It’s ‘Too Late’ To Extend ACA Aubsidies Without Major Disruptions, Some States and Lawmakers Say. Politico. [Online] October 16, 2025. https://www.politico.com/news/2025/10/16/its-too-late-to-extend-aca-subsidies-without-major-disruptions-some-states-and-lawmakers-say-00612001.

20. Ortaliza, Jared, et al. How Much and Why ACA Marketplace Premiums Are Going Up in 2026. Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. [Online] August 6, 2025. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/how-much-and-why-aca-marketplace-premiums-are-going-up-in-2026.

21. Rakshit, Shameek, et al. How Does Cost Affect Access to Healthcare? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. [Online] April 7, 2025. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/cost-affect-access-care/.

22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of DIsease Prevention and Health Promotion. Access to Health Services: Literature Summary. Healthy People 2030. [Online] [Cited: October 21, 2025.] https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/access-health-services.

23. Udalova, Victoria, et al. Who Makes More Preventable Visits to the ER? U.S. Census Bureau. [Online] January 20, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/01/who-makes-more-preventable-visits-to-emergency-rooms.html.

24. Scott, Kirstin Woody, et al. Assessing Catastrophic Health Expenditures Among Uninsured People Who Seek Care in US Hospital-Based Emergency Departments. JAMA Health Forum. [Online] December 30, 2021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8796980/.

25. Maas, Steve. Hospitals as Insurers of Last Resort. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] September 5, 2015. https://www.nber.org/digest/oct15/hospitals-insurers-last-resort?page=1&perPage=50.

26. Karpman, Michael, Coughlin, Teresa A. and Garfield, Rachel. Declines in Uncompensated Care Costs for The Uninsured under the ACA and Implications of Recent Growth in the Uninsured Rate. KFF. [Online] April 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/declines-in-uncompensated-care-costs-for-the-uninsured-under-the-aca-and-implications-of-recent-growth-in-the-uninsured-rate/.

27. Sullivan, Leila. June-July Research Roundup: Anticipated Effects of H.R. 1 on Health Insurance Coverage, Affordability, and Uncompensated Care. Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms. [Online] July 24, 2025. https://chir.georgetown.edu/june-july-research-roundup-anticipated-effects-of-h-r-1-on-health-insurance-coverage-affordability-and-uncompensated-care/.

28. Blavin, Frederic. Reconciliation Bill and End of Enhanced Subsidies Would Cut Health Care Provider Revenue and Spike Uncompensated Care. Urban Institute. [Online] May 29, 2025. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/reconciliation-bill-and-end-enhanced-subsidies-would-cut-health-care-provider.

29. Michel, Adam N. Six Reasons to Not Extend the Enhanced Obamacare Subsidies. Cato Institute. [Online] October 7, 2025. https://www.cato.org/blog/six-reasons-not-extend-enhanced-obamacare-subsidies.

30. Capretta, James C. Health Care Subsidies Are a Political Shortcut, Not a Lasting Policy Solution. The Dispatch. [Online] September 30, 2025. https://thedispatch.com/article/congress-aca-subsidies-credits-lower-health-care-costs/.

31. The Commonwealth Fund. The State of Health Insurance Coverage in the U.S.: Findings from the Commonwealth Fund 2024 Biennial Health Insurance Survey. [Online] November 21, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2024/nov/state-health-insurance-coverage-us-2024-biennial-survey.

32. Aron-Dine, Aviva, Einav, Liran and Finkelstein, Amy. The RAND Health Insurance Experiment, Three Decades Later. J Econ Perspect. 2013;27(1):197–222. [Online] https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.27.1.197.

33. Maas, Steve. The Impact of High Deductibles on Health Care Spending. National Bureau of Economic Research . [Online] December 1, 2015. https://www.nber.org/digest/dec15/impact-high-deductibles-health-care-spending?page=1&perPage=50.

34. Notowidigdo, Matthew J. and Gross, Tal. Healthcare and the Moral Hazard Problem. Chicago Booth Review. [Online] July 22, 2024. https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/healthcare-moral-hazard-problem.