Congress spent much of 2017 debating block grants and other caps on federal Medicaid spending but ultimately did not enact those plans into law. Today, the topic has resurfaced both at the federal level and in the Tennessee General Assembly.

Below, we explain what remains unknown about current proposals. These missing details could affect both the state budget and the 1.3 million Tennesseans who get health insurance from TennCare, our state’s Medicaid program.

Key Takeaways

- A Medicaid block grant would cap federal funding to state Medicaid programs —slowing the expected growth of federal costs.

- Proposed Medicaid block grants often also seek to give states more responsibility over program design, like benefits and eligibility.

- Federal funding for TennCare would depend on details that are not yet known. The degree to which states would gain flexibility on program design rules is even less clear.

- These policies could create challenges, opportunities, and difficult trade-offs for state policymakers required to balance the budget.

Current Medicaid/TennCare Block Grant Proposals

The Tennessee General Assembly is considering legislation (HB 1280/SB 1428) that would take a step toward converting TennCare into a block grant. The amended version that passed the state House Insurance Committee on March 3, 2019 would require the governor to seek federal approval to receive federal TennCare funding as a block grant. The governor would have four months to submit the waiver and, if the federal government approved the plan, would need the legislature’s approval to implement it. (1)

One assumption in President Trump’s proposed FY 2020 federal budget is that federal financing of Medicaid would change to a block grant or per capita cap beginning in 2021. Many details of the Trump proposal are not yet available, but federal budget documents note that it is modeled on the Graham-Cassidy plan Congress considered in 2017. (2)

What Is a Block Grant?

Traditionally, “block grants” are federal grants that give states broad flexibility on how to allocate the money to achieve a specific purpose or program goal. The amended version of HB 1280/SB 1428 envisions this kind of block grant for TennCare. Recent federal proposals have not envisioned this type of block grant for Medicaid.

Historically, federal proposals to create Medicaid “block grants” would have capped federal Medicaid funding — either in total or on a per-enrollee basis. Many (but not all) have also included reforms to give states more flexibility to manage their program costs within the federal funding caps.

An Example of a Traditional Block Grant

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is an example of a traditional block grant. States have flexibility to allocate federal TANF dollars across four broad benefit types, with the stated goal of helping low-income families achieve self-sufficiency. (3) This flexibility translates to significant differences across states in spending and the types of services funded. For example:

- In FY 2017, Tennessee was awarded $191 million in federal TANF funding and spent $67 million — or 35%, the lowest share of any state in the country.(4)

- Tennessee allocated about 62% of its TANF spending on cash assistance. Among bordering states, that figure ranged from 8% in Mississippi to 70% in Kentucky.(4)

- As of July 2018, Tennessee’s TANF benefit for a single-parent family of three was $185 per month. Among bordering states, it ranged from $170 in Mississippi to $419 in Virginia.(5)

How a Funding Cap Would Affect Federal Medicaid Spending

At the federal level, a primary goal of turning Medicaid into a block grant would be to slow the growth of federal Medicaid spending. For example, President Trump’s proposed FY 2020 budget would let federal Medicaid funding grow no faster than general inflation. That is slower than the growth expected under current law. (2)

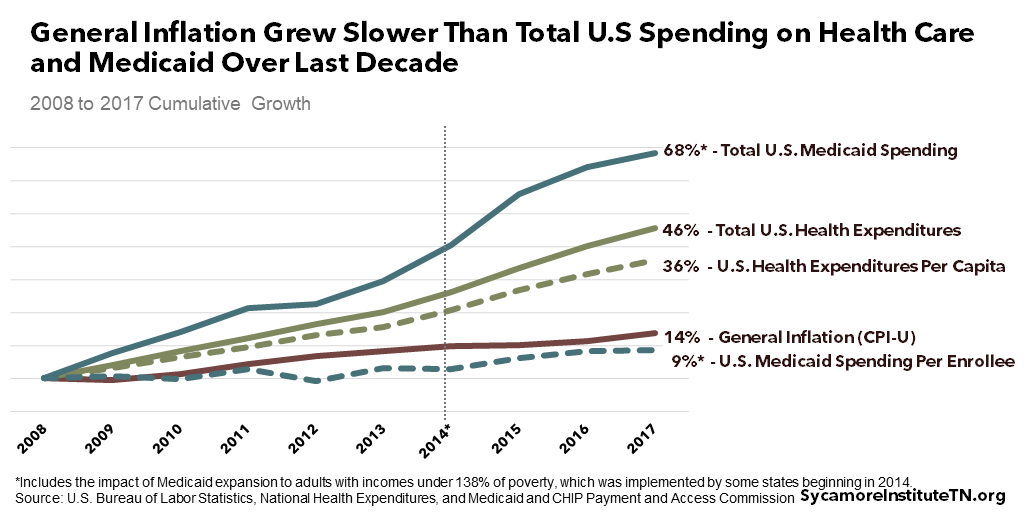

For comparison, general inflation grew slower over the last decade than total and per capita U.S. health care spending and total U.S. Medicaid spending. Meanwhile, it grew faster than U.S. Medicaid spending per enrollee (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Currently, Medicaid is an entitlement program, which means that costs can be difficult to predict. Coverage of many services is guaranteed to all who are eligible, so spending largely depends on how many people enroll, what their health care needs are, and how much their services cost. The federal government pays a specific share of whatever the Medicaid costs are in each state (about 65% in Tennessee), and the state pays the rest.

Under proposed caps, federal payments would not exceed certain levels no matter how much the program costs. For the reform to save money at the federal level, at least some states would see a smaller increase in federal funding than would occur under current law. The ultimate financial impact would vary by state and depend on many still-unknown details, including those discussed in this policy brief.

How TennCare Benefits & Eligibility Might Change

Proposals to cap federal Medicaid funding often seek to give states more control over program design (e.g. benefits, eligibility, enrollee responsibilities). Federal laws and regulations governing how federal dollars can be used, for example, define the core populations and benefits that states must cover and the optional populations and benefits that states may cover. More flexibility could allow states to deviate from those requirements and still receive federal Medicaid dollars. This may allow states to use their own discretion to cut costs to stay within federal funding caps.

HB 1280/SB 1428 seeks to use federal waiver authority to gain this type of flexibility. The federal government can waive some federal Medicaid rules to let states try innovative approaches (see text box). State Medicaid officials and the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) negotiate the details of these waivers. The extent to which that can occur without changing federal law is unclear. (9)

A summary of Trump’s proposed budget mentions new flexibilities for states to determine benefits, eligibility, and enrollee cost-sharing and work requirements. (10) Detailed information is not yet available, but the 2017 model for this proposal gave states two options. One option had a more generous funding cap without broad flexibilities, while the second option had a less generous cap with more flexibility to define eligibility and benefits. (11) The U.S. Senate’s budget reconciliation rules limited the type of policy changes that bill could include.

The TennCare Waiver

TennCare has operated under a waiver since 1994. The 1994 TennCare waiver was the first of its kind in the country — using existing flexibilities to produce cost-efficiencies with managed care. Policymakers used those expected savings to make another 300,000 uninsured adults eligible for TennCare. In 2005, however, financial constraints led TennCare to reduce eligibility and remove many enrollees from the program.

Today, TennCare taps existing flexibilities to cover some optional eligibility groups and benefits while waiving some federal requirements. For example, the TennCare CHOICES programs cover home- and community-based services for some low-income individuals with disabilities who are at risk for needing nursing home level of care. At the same time, it waives federal requirements for retroactive eligibility — among others. (18)

The current TennCare waiver is subject to some federal financial constraints. Like all waivers, TennCare must meet federal “budget neutrality” requirements. In other words, a state waiver cannot cost the federal government any more than it would be expected to spend in the absence of the waiver. (19) This standard is applied to TennCare at the enrollee level— akin to a per capita cap — for some (but not all) costs over a five year period. (18)

Factors That Would Determine Federal Funding

Federal funding for TennCare would depend on details that vary from one plan to the next, sometimes with room for administrative negotiation. This section outlines how recent proposals address some of these details.

A Grant or a Ceiling?

Federal funding caps might function as either a grant or a ceiling.

- The amended version of HB 1280 appears to envision Tennessee getting a lump-sum grant and discretion on how much of it to spend.

- Most plans Congress debated in 2017 would have put caps on the existing funding structure. Until reaching the cap, the feds would cover state costs at the normal Medicaid match rate. Most of the proposals did not let states that stayed below the cap spend the remaining federal funds, although the Graham-Cassidy plan did so in a limited way.(11)

- Trump’s budget is unclear on this point, but it may follow the Graham-Cassidy approach.

Effects of Enrollment Changes

Federal caps may or may not account for changes in enrollment. TennCare is a counter-cyclical program, which means enrollment typically increases as people lose jobs and income during economic downturns. For example, from FY 2008 to FY 2009 during the Great Recession, TennCare’s enrollment grew by over 50,000 people.

- Both Trump’s proposal and the Graham-Cassidy plan on which it is based would let states choose between a per capita cap that varies with enrollment or a lump-sum block grant that does not change with enrollment.(10) (11)

- HB 1280/SB 1428 is silent on this point.

Choosing a Reference Point

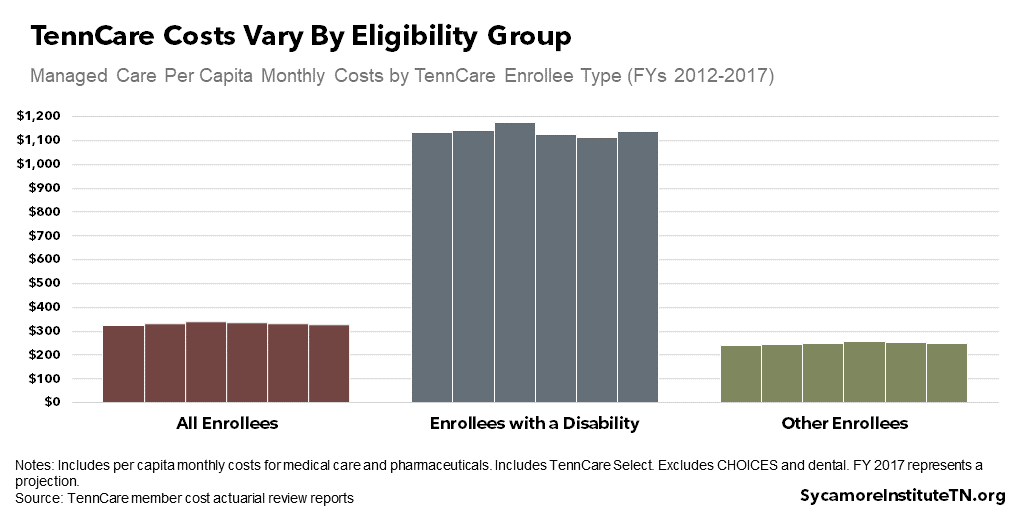

Federal funding caps are often based in part on how much a state spent in a designated year, known as the base year. Over the last decade, Tennessee has been relatively effective at cost-containment (Figure 2), which could generate a comparatively lower base than other states’.

- The plans Congress debated in 2017 used base years from recent history to avoid incentivizing states from making spending choices intended to raise their future funding caps.(11)

- The base year for Trump’s proposal is not yet known.

- HB 1280/SB 1428 does not specify a base year.

Figure 2

What Is the Growth Rate?

Once the base year has been set, the funding cap for any given year depends on a pre-determined growth rate.

- President Trump’s proposal and HB 1280/SB 1428, as introduced, would tie growth to general inflation.

- The amended version of HB 1280 does not specify a growth rate.

- Previous Congressional plans have included a variety of growth rates, including general inflation, medical inflation, and medical inflation +1%.(11)

Group-Specific Differences

A state’s Medicaid enrollees may not all be subject to the same federal funding caps. TennCare has multiple eligibility groups, each with different health care needs and spending patterns (Figure 2).

- The Graham-Cassidy plan on which Trump’s proposal is based applied different growth rates to separate caps for children, adults without disabilities, the elderly, and enrollees with disabilities.(11)

- Some plans Congress debated in 2017 excluded adults with disabilities and children from the caps entirely — including Graham-Cassidy’s block grant option.(11)

- HB 1280/SB 1428 appears to apply to all eligibility groups currently covered by TennCare, although the administration may have flexibility to exclude some groups.

What These Factors Mean in Practice

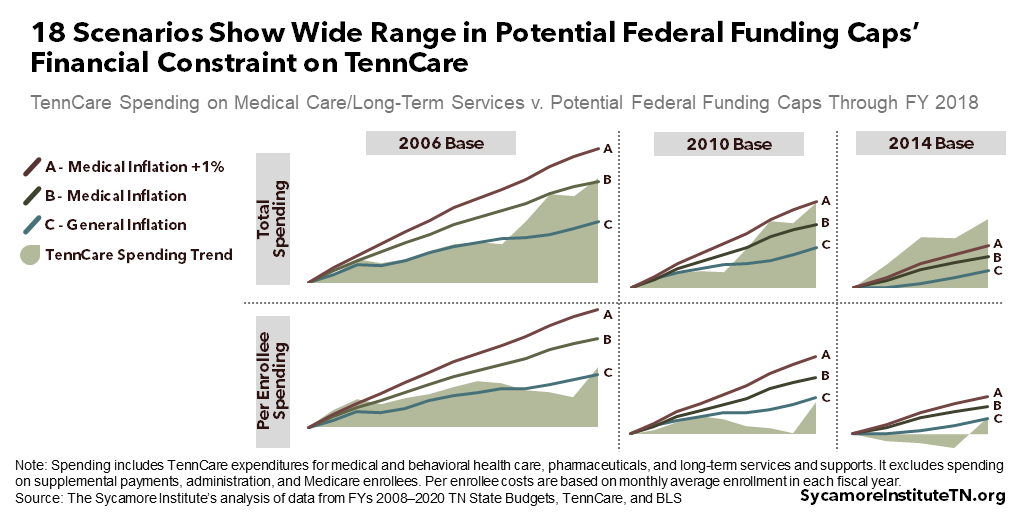

Figure 3 shows 18 different scenarios for how TennCare spending through FY 2018 would have compared to potential federal caps. For simplicity, it considers only three of the variables discussed above: the growth rate, the base year, and whether the caps apply to total spending or on a per-enrollee basis. Growth in TennCare’s costs over the last decade have not tracked closely with any proposed growth rates. As a result, some scenarios represent more or less financial constraint on TennCare.

A variety of factors have influenced TennCare’s spending trend. Examples include cost-containment measures implemented after the 2005 disenrollment, the Great Recession from 2007-2009, the introduction of costly new medical treatments (e.g. drugs that cure Hepatitis C), and the 2014 suspension and 2016 reinstatement of annual eligibility redeterminations.

Figure 3

The Unknowns of State Flexibility on Program Design

The degree to which states would gain flexibility on program design rules is even less clear than how federal funding would change. This section outlines some of the key questions and unknowns.

Which Rules Would Be Open to State Discretion?

Existing federal Medicaid laws and regulations set out broad requirements for how state Medicaid programs must operate. For example:

- States must make available an appeals process for both benefits and enrollment.

- States must cover certain benefits, like hospital care. Other benefits like chiropractic care, adult dental, many home and community based services, and even prescription drugs are optional.

- States are not allowed to charge certain enrollees premiums or cost-sharing — including most adults with income under 150% of the poverty level and most children. (16)

Precisely which federal Medicaid rules might become open to state discretion is unclear at this time. Current proposals at the federal level and in the Tennessee General Assembly do not include this level of detail, and it is unclear what is possible under current federal law.

Why Would States Use This Discretion?

States seeking to use potential new flexibilities would likely have at least one of three goals in mind: (1) to reduce costs, (2) to limit or enhance provider payments or coverage for certain populations, and/or (3) to keep spending within federal caps. Tennessee’s use of any new flexibilities would depend in part on how much financial constraint — if any — TennCare experienced under a federal cap. See Figure 3 for examples of the wide range in potential financial constraint.

How Would State Discretion Affect Enrollees and Providers?

States’ use of new flexibilities would likely affect both enrollees and providers. As an example, consider Tennessee’s existing waiver from the federal Medicaid rule that states must provide new enrollees with up to three months of retroactive eligibility. (17) Waiving this rule saves TennCare money, which it uses to fund other optional enrollees and benefits. (18) As a result, an eligible low-income mother who does not enroll in TennCare until after an emergency room visit would be responsible for the costs of that visit. If she cannot pay, the hospital would bear the immediate costs of uncompensated care.

The Trade-Offs of Medicaid Block Grants

Medicaid reform proposals represent a significant shift in responsibility for how Medicaid is financed and managed. The federal government would get lower, more predictable costs by capping its financial obligation while giving up some say on how those dollars are spent. While some states could conceivably see an increase in federal Medicaid funding compared to current law, overall, states would receive fewer federal resources. In turn, states would have more discretion and bear more responsibility for the structure of their Medicaid programs.

The details will determine the challenges and opportunities that shift creates for Tennessee. The amount of federal funding for TennCare and the amount of flexibility given to state policymakers would both depend on many important details, including those discussed above, that are currently unknown.

Each potential challenge and opportunity would present trade-offs for state policymakers. For instance, achieving cost-savings for taxpayers and/or providing a slimmer TennCare benefit to more people may have negative effects on current TennCare enrollees. Alternatively, any downward pressure on federal TennCare funding might require state policymakers to balance the budget by reducing TennCare eligibility and benefits, cutting provider payments, requiring more of enrollees, shifting money from other priorities, and/or raising taxes. All of these decisions would pose trade-offs.

Want More Sycamore Analysis of Medicaid Block Grants?

Understanding Medicaid and TennCare (June 1, 2017)

Medicaid Reform 101: More Than Just Block Grants (January 26, 2017)

How U.S. House Medicaid Reforms Could Impact TennCare (March 10, 2017)

TennCare’s Federal Funding under the AHCA (March 14, 2017)

How the U.S. House Health Bill Affects Tennessee (May 10, 2017)

The American Health Care Act: Rural Health & Tennesseans with Disabilities (June 22, 2017)

Comparing TennCare Spending Growth to the Caps Proposed by Congress (June 23, 2017)

Graham-Cassidy’s Impact on Tennessee (September 26, 2017)

References

Click to Open/Close

- Tennessee General Assembly. HB 1280 / SB 1428. 2019. Accessed on April 4, 2019 from http://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/Default.aspx?BillNumber=HB1280.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). FY 2020 Budget in Brief. March 11, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2020-budget-in-brief.pdf.

- Administration for Children & Families Office of Family Assistance. About TANF. June 28, 2017. Accessed on March 13, 2019 from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about.

- —. TANF Financial Data – FY 2017. September 27, 2018. Accessed on April 4, 2019 from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/tanf-financial-data-fy-2017.

- Burnside, Ashley and Floyd, Ife. TANF Benefits Remain Low Despite Recent Increases in Some States. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. January 22, 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-benefits-remain-low-despite-recent-increases-in-some-states.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Historical Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U): U.S. City Average, All Items, Index Averages. December 2018. Accessed on March 14, 2019 from https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/supplemental-files/historical-cpi-u-201812.pdf.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). National Health Expenditures: Aggregate and Per Capita Amounts. February 20, 2019. Accessed on March 14, 2019 from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicaid Enrollment and Total Spending Levels and Annual Growth, FYs 1966–2017. July 24, 2018. Accessed on March 14, 2019 from https://www.macpac.gov/publication/medicaid-enrollment-and-total-spending-levels-and-annual-growth/.

- Sullivan, Peter. Trump Officials Consider Allowing Medicaid Block Grants for States. The Hill. January 11, 2019. https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/424988-trump-officials-consider-allowing-medicaid-block-grants-for-states.

- White House Office of Management & Budget. FY 2020 Budget of the U.S. Government. March 11, 2019. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/budget-fy2020.pdf.

- U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy (LA). Graham-Cassidy Section by Section. September 13, 2017. Obtained from https://www.cassidy.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/senators-introduce-graham-cassidy-heller-johnson.

- Aon Consulting. Actuarial Review of the TennCare Program for FYs 2003-2017. Obtained from https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/information-statistics/actuarial-report.html.

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee State Budgets for FY 2008-FY 2020. Obtained from https://www.tn.gov/finance/fa/fa-budget-information/fa-budget-archive.html.

- Tennessee Division of TennCare. Enrollment Data. Obtained on March 14, 2019 from https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/information-statistics/enrollment-data.html.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Medical Care in U.S. City Average, All Urban Consumers, Not Seasonally-Adjusted 12-Month Change. December 2018. Data obtained from https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Federal Requirements and State Options: How States Exercise Flexibility under a Medicaid State Plan. August 2018. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/federal-requirements-and-state-options/.

- Musumeci, MaryBeth and Rudowitz, Robin. Medicaid Retroactive Coverage Waivers: Implications for Beneficiaries, Providers, and States. Kaiser Family Foundation. November 10, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-retroactive-coverage-waivers-implications-for-beneficiaries-providers-and-states/.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). TennCare II 115(a) Demonstration Waiver. Octber 23, 2018. https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/policy-guidelines/tenncare-1115-demonstration.html.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Setting Per Capita Caps. March 2017. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Setting-per-capita-caps.pdf.